Emerald Fennell on ‘Saltburn’: “I think in many ways my work isn’t dark enough”

You might know Emerald Fennell from her show-running the second season of Killing Eve. You might know her face from her playing Camilla Shand in the third and fourth seasons of The Crown. You might know her for her 2020 Oscar-winning directorial debut, Promising Young Woman. If you don’t know her at all, this year, that’ll be corrected as the multihyphenate gears up to release her most prominent and striking project to date, Saltburn.

For Hammersmith-born Fennell, the notion of making an audience uncomfortable is something she just cannot resist. After being awarded the famed golden statue with the aforementioned Promising Young Woman – a revenge drama touching on the broad social attitudes towards sexual violence against women – the multi-hyphenate has now returned with her sophomore feature film. The darkly comedic Saltburn centres on a group of wealthy Oxford students who escape to a luxurious estate in the summer and tells a tale of privilege and unequivocal lust and desire. Featuring an ensemble cast of some of the most critically revered actors on the globe, including Barry Keoghan, Jacob Elordi Archie Madekwe and Sadie Soverall, Saltburn has managed to capture the zeitgeist thanks to its delicious serving of class, sex, ambition, trauma and dead-eyed emotion.

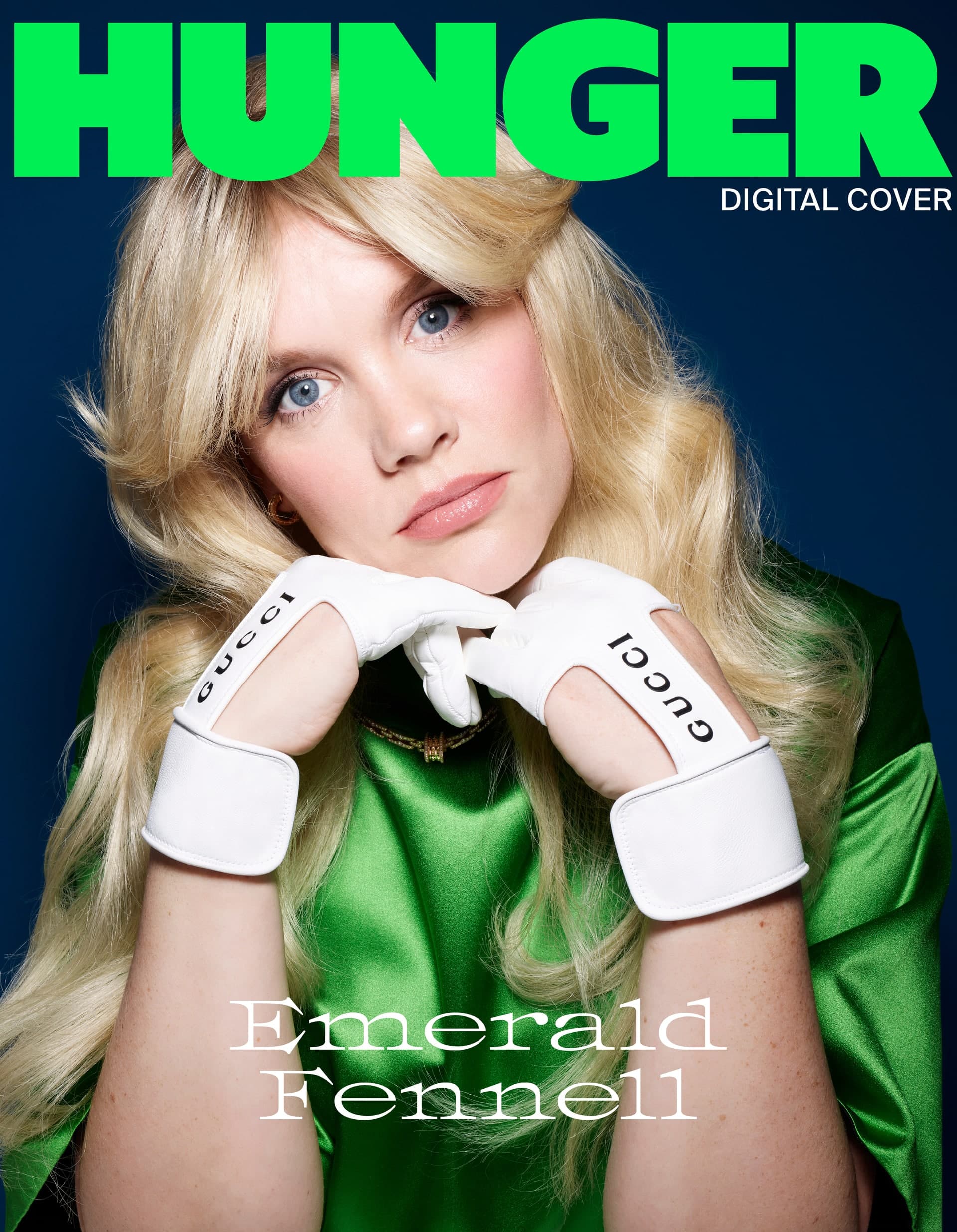

Now, with the film’s UK theatrical release set for November 17th, iconic British photographer Rankin sat down with Fennell to discuss the intricacies behind Saltburn, working with Keoghan, and the importance of transcending genres.

Rankin: Why didn’t you cast yourself?

Emerald: If I’d come in to audition, I wouldn’t have given myself the part. I don’t know if I’m able to cast myself in something because then that film would just be me in slow motion with a wind machine in my face, highly airbrushed, and reading a magazine. There’s no way that I could put aside my own horrific personal vanity to shoot myself.

R: Are you always this honest?

E: Yes.

R: Where does that come from?

E: I mean I’m not that honest, but I like to scrutinise the ways that I’m not honest. It’s sort of a necessary part of having a sense of humour, isn’t it, that you’re kind of reasonably self-aware? Nobody can be completely self-aware. I’m aware that I’m an absurd figure. Everything about my work is about being honest. It’s about the stuff that’s challenging or troubling by trying to look at it in a way that’s funny and dark and makes it a bit less difficult to talk about.

R: More about being able to pursue something that’s complicated?

E: The people that I like, I want to get into it. I want to get right into it straightaway. When you meet someone, if you don’t have to do small talk, it’s just such a relief. Part of the way I cast things is I’ll meet the actors first just to get an idea of what they’re like because I want to know what they’re not. It’s not about honesty, because liars are some of the best people in the world, certainly the most amusing people. But more about are they willing to engage with things that are difficult about themselves? Are they open to an uncomfortable conversation? With actors I often ask, ‘do you like being famous?’ What you’ll find is lots of actors will say, ‘God, no, it’s a nightmare.’ But some of them will say ‘Yes’.

R: Do you like being famous?

E: I’m really not, like really not. I think partly the reason why I I love directing and writing is it is the thing I like doing most. Partly the reason why I’m not acting so much anymore is I just don’t. I don’t like it, she says, dolled up on the cover of a magazine. Hate it. So disingenuous, isn’t it? So I don’t know. Then that’s the answer truthfully, isn’t it?

R: You’re not famous?

E: I absolutely go about my everyday life in a way that’s completely normal and that is really nice. And that’s something that I value. I think the level of scrutiny, particularly if you’re a famous woman, is just unbearable to me. I’m not a particularly nice person or a particularly glamorous day to day person so I just wouldn’t survive the scrutiny.

R: For me when I watch the film, one of the things that I really felt like was that a man was directing the men, only because I felt you had an understanding of them in a way that I haven’t seen before in a lot of films. Men written by men is something seen a lot. You obviously have a good relationship with men, how do you get on with men as opposed to women? Is masculinity something you look at?

E: I think my life has been completely even in that regard, although I would say most of my close friends are women. My friendship group is evenly split. I guess it’s not really something that I thought about very much. I was just interested in this story and absolutely in masculinity in the way that obsession and desire are particular to men in a certain way. But I guess this is a story that could have equally been about women. It just so happens that this gothic sub-genre of ‘something that happened in the country house one summer’ tends to involve a close male friendship. After Promising Young Woman came out and I showed early cuts to some friends of mine – half men, half women. One of the men had been at university with me and he was a bit shaken. I said ‘Are you alright.’ And he said, ‘I just felt like you were watching us.’ I suppose that’s all it is. I may be a little like Oliver in the regard that I like watching people and listening to them and I’m interested in what they’re really saying or thinking, which is then useful.

R: The idea of writing for men or writing for women, it obviously doesn’t worry you at all. You’re just happy with both because you’re drawing on a lot of your own experiences?

E: I didn’t really think about it. It’s usually the character and the character comes kind of unbidden to me, a bit like imaginary friends. So in a lot of ways, I don’t have a huge amount of control over who or what I’m writing about. And it’s only later that I realised what something was about. Often when you talk about a movie or something you’ve made, people want you to talk about themes. It’s not necessarily something you think about when you’re writing or making something, because people want to know thematically what you’re talking about. But actually, if it comes from inside you, you’re not thinking in that way, really. It’s only now people have asked why now? The answer for ages was because it was a thing I wanted to write, but now I’m able to kind of look at it more clearly. I’ve got a bit of distance from it.

I think it makes total sense that it’s a post-COVID movie that actually during COVID we were only allowed to watch people, that we were forbidden from being in the same room with them, let alone touching and let alone kind of sharing fluids of any kinds. You know, fluids were just forbidden. You were not allowed to breathe next to each other. So now I’m far enough away, I can see that this is about that and distance. Maybe female friendships and relationships tend to be more tactile or in my experience, have been a bit more tactile or certainly would have been in 2007 when the film is set. There needed to be that level of physical distance and restraint that was sort of necessary in this kind of film or genre.

R: Like a release?

E: I felt if you take the most restrained British literary tradition, if you take the Brideshead go-between – that sort of super restrained way of writing or shooting – well, what happens when you take the restraints off? What happens when you just take the brakes off altogether and just let the car crash or let the thing happen that pulsing always underneath all that jealousy, all that sex, all that longing, all that fury. Let it happen. Don’t just end with a longing glance, but end where it feels like a gothic ending in total annihilation.

R: You said before about the subgenre that you absolutely absorbed and loved those things in the past, which is why when we were talking, I was like, I get it. So basically what you’re doing is taking the restrained and holding a mirror up to what we were like in the noughties, especially because what I really loved about it was the fluidity of it. The question I would ask is, was that something that was intentional or was it that you literally came from experiences because I’ve had experiences like that. I’ve had experiences in that situation. So taking those experiences and putting them into that really amazing situation where we’d all love to go and experience that place, was that intentional?

E: I’m not a very good memoirist. Of course you observe things as you go about your life, but I suppose it is more that it felt like a really useful way of looking at our sadomasochistic relationship with the things that we want and the things that never want us back. It helped that it was in the recent past because I think it’s more humanising that it was 15 years ago. We’re not able to see ourselves very clearly now. You know more about Felix because he’s got a carpe diem tattoo and he’s wearing baggy Carhartt bootcut jeans and he’s got a Livestrong bracelet and Venecia is the richest, most beautiful girl in England, but she’s still got two inches of roots and a bad dye job and bad extensions and St Tropez tan clotted around her hands. It was that era. It’s humanising to see people like that. I think where these people could be so unrelatable, it kind of gives them this thing that they’re just as fallible. They’re just as likely to fall for kind of crappy trends as all of us are. I think that’s really important because this isn’t just a comedy of manners. It’s not just a satire of the aristocracy, although that’s part of it. It isn’t just in England or Britain, but it is a global obsession with things we can’t have. There’s a really interesting cycle that you keep seeing that I am part of and why I wanted to interrogate it, which is that and this hope and everything here is part of it too. You look at someone and you don’t know them. You look at them on the internet and you know everything about them. You know their children. You know what food they eat. You know what wallpaper they chose. Everything about them. You’re obsessed with them. But you also have a feeling that it was slightly superior, that you’re somehow a voyeur and you are lusting after them or their life or whatever it is. You also feel this superiority, which is entangled with a self-loathing because there’s something slightly disturbing about this level of knowledge about a stranger, and that watching, voyeurism, and self-loathing then hardens into something weirder, which is a dislike for them. A desire for schadenfreude. You start thinking and you see it all the time very clearly. An obvious example is men on the internet who want to fuck women and say they hate them and they write the most repellent stuff to them. The root of that is a sex thing. I do know that it’s such a convoluted answer, but I think that yes, it’s a satire ostensibly about one thing. But I also think it’s about us. It’s about the people who want it, those of us who feel we should know better but we are still on our knees for the clothes and the houses and the beauty. We would still go down to breakfast and feel mortified if we got the rules wrong. We’re all entangled in this thing. It’s fascinating.

R: Were you obsessed with the details in it because it felt that when I watched it, it was very familiar at the same time, which was really strange and I went away and thought I wonder if she was really obsessive about getting everything right so that she could let it go. At the same time I feel myself up in the film and that’s a very unique and unusual place. Was that something that you worked on?

E: I think it’s so much about directing, actually. More than writing is making sure that you are being aware that the audience needs to watch a film and immediately relax. It is that kind of film. It’s a familiar film. You know this genre, you know this narrator, you know this place. And then you can use that familiarity. What you’ve got is people who are relaxed and it’s much easier and it’s more dangerous to punch people in the stomach when they’re relaxed. I think that’s part of the thing of making a thriller and making something about sex, that you are caught unawares, that there’s a sudden stomach flip moment when you suddenly don’t know quite where you are. For me, if you are making a film, it’s a very specific artform. It’s contained and it can be expressionistic, or it can be more metaphorical. You can take people to places that would be relentless in any other art form or to surface whatever it might be. So the idea that I’m kind of obsessed with this thing is that as a director, you make obviously a thousand decisions every hour, little tiny decisions. And those decisions are the same decisions that you make when taking a photograph. It’s not just the technical side of things, but it’s also if they’re drinking a cup of tea, a lot of the time you’d be like x drinks cup of tea. What you’ll have is somebody who will just have brought tea on set already. For me though, it’s Richard Grant in this film who lives in this enormous house. What kind of teacup would it be? It’s not going to be bone china, even though you might be tempted to do that. It’s actually going to be a kind of really crappy mug he’s had for years that was given to him by a friend, which says ‘His Lordship;, which is kind of a funny, tough joke. It’s chipped and it’s actually a bit grubby around the rim. You’ve got a bit of tea stain in there because there’s a grossness to having things too clean or having things that are too posh. There’s the teacup. Then, is he leaving the bag in? How does he take it? Do we see him put in seven spoons of sugar? All of these decisions take you somewhere and they tell you something about character and then that’s just one thing you know. We were saying that Rosamund’s character, Elspeth, would have been a big model in the early nineties or certainly an it girl. Maybe never quite as big a model as she wanted to be or felt she should have been. We made her David Downton style. We had two portraits of her, but you’re not going to just get a regular oil painting of her. You get a David Downton, but you get a Rankin style photograph taken of her from her modelling days. You don’t even see them. But they’re part of the texture. You might see them for a second, but they are part of the texture of these people’s lives. It means that not only is it on screen, but when the actors come in, they know where they are. We thought that Elspeth would have had a phobia of all animals. If there’d been a pet, I would have wanted to have seen her. It’s mad not to.

R: I mean you seduced me into being there and living that life. I knew it was going to become a thriller because I’d heard about it. But at the same time, the way you did it was really clever. I didn’t really know where it was going, and you did a genre film that is a genre within a genre within a genre, and there is even probably another genre at the end of the film. I wondered how hard that was to persuade everyone, not the actors, but the people that were financing it to do it, because it’s not a simple film.

E: It’s a few things. I’m quite determined, just from a practical point of view. As a producer as well, you’ve got to make things for a reasonable amount of money, so that’s the first thing. But you’re able to afford yourself a few more creative risks.If you’re able to make something look more expensive than it was. For example, every brilliant person who worked on this, you know, combined – it wasn’t like a low budget film, but maybe cost less than it looks like it cost. Immediately you’re able to say. Promising Young Woman was very, very low budget. Both these things make you able to say, look, trust me and what’s the worst that could happen? The worst thing is if you make something that falls between two stools. It’s the instinct to always soften things and make them more comfortable, palatable, and a bit more generic. For me, it is the conversations I have to have, like trust me that this is going to be more interesting and that there will be people who won’t like it for all sorts of reasons. But the people who do like it and do get it will really connect with it and really love it. It’s always a back and forth conversation, but I’m not really interested in making something that isn’t a bit messy or tricky, and that people aren’t going to have a different relationship with it. I don’t see the point.

R: Great movies are ones where you walk away and you think about it for a week or so. I wonder why and what that looks like. It’s almost a moral dilemma. I think that that’s what I got out of it. I know that you said earlier you were your watcher, but how did you get into Barry’s head? Or Oliver’s head? You’re from a very different background and I’m sure you’ve met people like that, but you seem to capture in a way that I was probably the most impressed by that than I’ve ever seen.

E: It’s a difficult one talking about Oliver, because there are so many differences between all of us. Thing is I made him up – he’s in my head. I don’t know how to separate him from me. When it came to meeting Barry, it was so exciting because I knew he was in his head too. And then you have this unbelievable excitement and I had it with Carey too. Actually I’ve had it with every actor I’ve worked with. You then end up with this sort of telepathy, which means you can push each other harder and you both have this equal ownership. For me and Barry, we are able to and only interested in pushing something harder and deeper and making it more complicated and difficult. That’s where it’s exciting. That’s why I loved meeting Barry the first time he sat down and he just said, ‘I am Oliver.’ And then he told me all the ways in which he was Oliver. He engaged with the difficulty of that character in a very honest way. Because I did, too, it meant that none of the things that happened in the film just came from my tawdry imagination. I have to take some level of responsibility for them.

R: What’s next? Are you encouraged now to go even deeper into that? Is there going to be a darker side because it’s fucking dark already.

E: I suppose it is quite dark. Really dark. But then the things that I find dark are things that aren’t supposed to be dark at all. The things I find really dark are watching daytime television with people kind of combing over the disappearance of a child in a way that’s so salacious and then talking about cooking tips. I find our relationship with the things that we’re fascinated by under the guise that we’re titillated by, under the guise of like concern. I’m not really dark. I think we in our day to day lives are much more sadistic than ever. The things that people watch and listen to, myself included, are quite extreme. Therefore, I don’t know. I think actually in many ways my work isn’t dark enough. I’m interested in what we are not willing to do and what we are not willing to engage with about ourselves. I don’t know that that will ever change. I don’t know quite where it fits yet. I like making things that are different, so I don’t particularly want it to feel the same as this film. But you can’t escape yourself, I guess.

Saltburn is in cinemas Friday