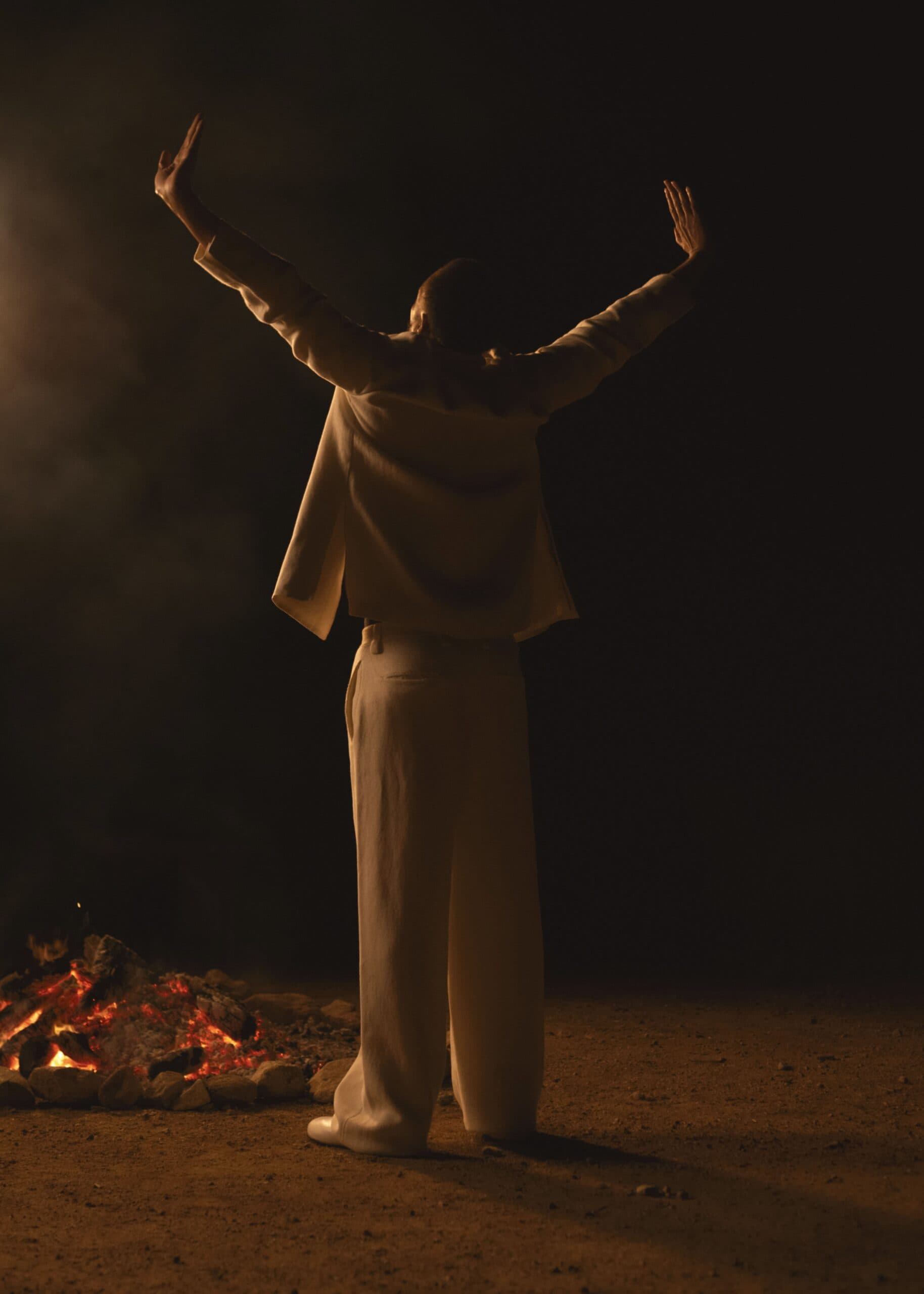

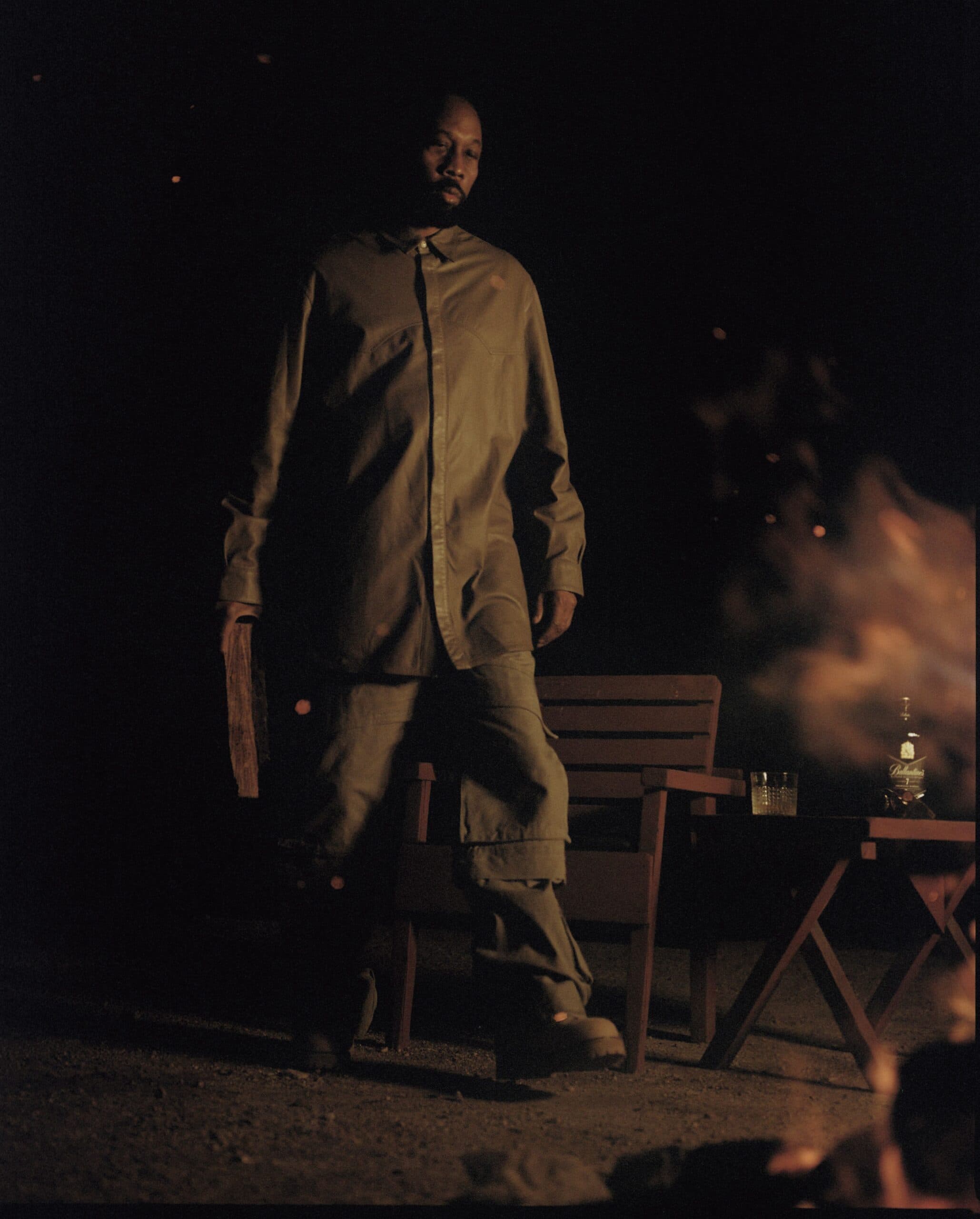

RZA: Catching life by the hook

- WriterRy Gavin

- Photographer Robin Harper

“Fishy, fishy, in a brook, daddy caught him by the hook,” RZA recites over the phone. He’s talking about his earliest memory of finding rhythm in words when he was handed a book of Mother Goose Nursery Rhymes as a kid and it sparked something in his brain. Fishy, Fishy, in a Brook was part of the anthology that became a cornerstone of most early memories, even to this day, publishing some of the greatest hits like Humpty Dumpty, Pat-a-Cake and Peter Piper. Yet it’s not a reference you’d expect the rapper and Wu-Tang Clan founder to bring up, nor is it the origin story you’d imagine RZA to have. When you think of the artist, it’s less “fishy, fishy” and more “Wu-Tang Clan ain’t nuthing ta fuck wit”. But, as the world has come to discover, he’s a man who has built on the unexpected.

We only hover on the conversation of nursery rhymes for about 15 seconds, but how else do you set about introducing a man like RZA, the architect of hip-hop, eminent scorer of films, ballet writer, director, actor, producer, Ballantine’s Scotch Whisky ambassador, father, son, and the holy spirit of modern-day rap? He’s a man whose interviews always start with: “RZA needs no introduction”. And it’s true. Anything you don’t know about the man, on your head be it. And if you have no clue who he is, it’s not just him you need to get to know, it’s a multisphere of music that excavated the ground, laid the concrete and foundations and built the house of hip-hop as we know it. Many musicians who younger generations would consider to be the greatest of all time have paid their respects to Wu-Tang and RZA – A$AP Rocky and Rihanna even named their first-born son after the 54-year-old.

The level of esteem and respect that RZA is held at within a multitude of creative industries goes further than the art, though. In fact, he says it would. There’s a connection to creativity, a wisdom around what it means to be an artist that could perhaps begin to explain the standard at which RZA has produced varying work through his life. A few pages into his books The Wu-Tang Manual and The Tao of Wu – philosophical insights into the group’s thinking and a guide to how to achieve it – will give a glimpse into his mind. Because what RZA started wasn’t just hip-hop, it was a movement, a way of thinking, an understanding that you can hear a nursery rhyme and one day become one of the – if not the – greatest rappers in history. So how do you introduce RZA? Well, you have to let the music do the talking.

When we speak, RZA is on his way from Los Angeles to Las Vegas to rehearse for the forthcoming Wu-Tang Clan residency that, by the time of writing, has already been hailed a triumph.

Ry Gavin: You must have spent some time in Vegas before. What does the place mean to you?

RZA: On the East Coast you’ve got Broadway, you’ve got a big art community. And then in southern California it’s more scattered. You can find some beautiful art, some beautiful places to go, but it’s not concentrated. So I usually go to Vegas for that art fix when I want to watch shows and be entertained.

RG: You’re no doubt the biggest hip-hop artists to have a residency in Vegas, true?

RZA: Yeah, up to date, we’re probably the first at this level. Hip- hop has passed through clubs, and you may go to a club like Drai’s and have an artist come through. You’ll get a thousand people in there, but as far as the residency and having a real theatre setting, hip-hop hasn’t achieved that yet, and we’re helping to pioneer that.

RG: The theme of the issue centres on the question, “Where’s your head at?” With you driving from LA to Vegas for a show that is as important to a musician as a lifetime retrospective is to a painter, your head must be in a pretty good place, right?

RZA: My head’s in a great space. I’ve been blessed to lose myself in art and creativity, and then been able to be fulfilled by being able to share it. I don’t want to be like Van Gogh, painting and painting and it doesn’t get shared until he dies, right? I guess it’s not too bad because it still got shared. But I’m fortunate that I’m able to share my art and share this state of mind while I’m here, share it with fans and other people in the artistic community.

RG: And what can you tell us about the residency?

RZA: I’ve designed this show for the Wu-Tang Clan and my brothers and we’ll get to rehearse and they’ll put their two cents in and change some of my ideas and help improve some of them. What I’m enjoying is that I’ve been able to take ideas from mere inceptions to reality. One of the best things I’ve done that really led to this extra creative freedom that I feel in my life right now is my ballet, Through Mud. You know, it doesn’t sound on-brand that RZA would write a ballet, but I did. Some of this acquirement will now be applied to Wu-Tang. Not in the same way as the ballet was, but just in the musicality of what I’ve gained in telling a story with the music that

I already created, and how I weave stories into the performance.

RG: How did the ballet come about? Were you sitting in the Bolshoi Theatre, watching Swan Lake, and thought, “I need to write a ballet”?

RZA: Covid gave us a lot of ideas, right? Sitting in the crib and, like the rest of the world, not knowing what’s going to be what. I dug up my old high school lyric book. There’s, like, 300 songs and a few hundred pages of lyrics. Some are just verses and some are songs that I probably started writing when I was 14 years old. I got hundreds of pages of my own childhood, of my own young mind. That’s recording my history through lyrics. As I’m reading through it, I’m coming across some of the ideas that I had in my head, being young, exploring, your first drink, your first smoke. And I have a friend named Evan Lamberg and I had a mini recording on me. We had dinner in New York and I played him a piece. He said, “That sounds more like you’re writing a ballet, like The Nutcracker.” And then I said, “You know what? That is more of my mindset.” And I pursued it as a piece of art that I wanted to see come to life.

RG: What does creating that, as well as writing 300 pages of lyrics at such a young age, and of course your body of work that is Wu-Tang, show you about your own creativity – does it all come naturally?

RZA: I’ve been blessed for it to come naturally. I remember when I got my book of nursery rhymes called Mother Goose. I would always read it in rhythm. And my uncle would walk into the house saying his old spirituals, you know, the elongated “Never laugh when the hearse goes by… ” That’s me hearing that at four years old. There definitely had to be some resonance of what was around me. As soon as I could express myself, I wrote my first lyric at the age of nine. I never stopped. Artists recognise that art is a wavelength, just like light. I had this theory for a while, and when I realised it, I was like, “Yo, if I wanted to dance, I could dance.” Why? Because as an artist I know I’m on the wavelength of art, you know what I mean? And not to name-drop, but what made me realise it was I was talking to my buddy Quentin [Tarantino]. I said I remember when I was young I was good at drawing and that’s what I did every day. I got up and started drawing faces or Disney characters. Then it went away as I continued to dive more and more into lyrics and music, right? Then he said he had the same ability. He said there was a moment in his life that passed through him. See, so it’s art. Art is a wavelength. And you have to tune the signal.

RG: That’s understandable, especially because for you and Wu-Tang there was always something there, an undercurrent of spirit and creativity that went deeper than the music. It’s something that some artists and creatives tap into.

RZA: That has to be a fact. And I think that scientists and psychologists could run some tests and prove it. I would say that the artist’s body is the antenna, and there’s something in their body as well. You know, whether he tuned it, whether it was a muscle he worked or whether it was something that he was born with, right? I don’t have the answer to that. It could be something that he learnt. This goes back to the old saying, “Great minds think alike.” Because they’re in tune with the same thing.

RG: That sort of wisdom and understanding was apparent in all Wu-Tang members from early on, wasn’t it?

RZA: I could agree with that. With any art it can be identified as an expression of emotions. Whether it’s a poet, singer, painter, dancer, violinist, the emotion is expressed through whatever form they’re shown in it. And as Wu-Tang Clan, our lyrics are an expression of our emotions. And the beautiful thing is that if those emotions weren’t expressed through the music and through the art, they could have found their way out another way, which is street violence, criminal activities. “Bring da motherfuckin’ ruckus” – I remember when I said that, and the intent of what I felt, you know what I mean? “Wu-Tang Clan ain’t nuthin’ ta fuck wit.” I used to kick the fucking walls in the studio. So the art became a way to get the emotion out and then that emotion is captured.

RG: Are there any artists around nowadays in whom you see that same level of emotion or passion, and tap into the same wisdom that you were tapping into?

RZA: I think a lot of the top artists all understand it and live it. Of course you hear it in Kendrick Lamar’s lyrics and his performances and J. Cole’s. I think Drake is a great example, right? He’s able to use his melodics and lyrical cadence.

RG: Do you see how what Wu-Tang created – something bigger than music – still resonates today in those artists and within the industry as a whole?

RZA: I’m very grateful that Wu-Tang still has the power of inspiration and the power of entertainment in an industry where most people don’t get a chance to make what they call a legacy. Most people have one album in and out, three to five years’ span. I’m grateful first and foremost, but I’m also conscious of it. When we said Wu- Tang Forever, that was after the accumulation of the success after five platinum albums. It’s almost like that’s the dream, the energy that we brought to the table – we want it to always be available to the world, in one form or another. And whether it’s coming directly from us or from someone inspired by us.

RG: I mean, I grew up in the countryside of England and, even then, me and all my friends grew up listening to Wu-Tang Clan. A$AP Rocky and Rihanna even named their kid after you. Your reach stretches far.

RZA: Yeah, well, we’re thankful. Know that.

RG: It’s also a desire to test yourself creatively and join dots together that you wouldn’t expect. Your partnership with the whisky brand Ballantine’s taps into that in a way.

RZA: Creatively my partnership with Ballantine’s inspired me to return to some of my vintage style of production, although I was using the modern MPC LIVE II, which has its own battery power source and built-in speakers that allowed me to compose tracks in the highlands of Scotland among the reindeer. The choice of drums and sounds I used was from my old crates of sounds. We also incorporated the vintage sound of the Mellotron and my son, Mel, added the bass lines from a vintage five-string Fender bass.

RG: What is it that you love about the spirit of Ballantine’s?

RZA: The idea of the whiskies being stored in barrels that date back to my first introduction to hip-hop [1976]. I was inspired to go to the roots. What I love about the spirit of Ballantine’s is the idea that correlates with my own ideas; the blending of various elements from different times and spaces can create something new and wonderful.

RG: A few people have said that before they got big and became successful, they always knew that there was more to their life and it was just a matter of time. They had this feeling. Did you ever feel like that?

RZA: With no ego, yes, I knew. Me and Ol’ Dirty [Bastard] used to talk about it when we was only 14 years old. We had something in us, we felt that we was gonna do something. I knew I was going to bring something. We had this inspiration and aspiration in us that knew that there was something bigger than ourselves that will even outlive us, potentially, that we’ll be a part of. And I guess it’s Wu-Tang at the end of the day. I was blessed in 2000 to travel to China to go to the Wudang Mountains, where the ancients of the Wudang philosophy built this temple to honour their teachings and to honour t’ai chi and Tao wisdom. I met the abbot, who told me that history already knew that I was gonna do it, what I was gonna make, make it popular in the West in a different way than it was in the East. He said that history knew that I was going to do it and he was happy to meet me. I was like, “Wow.”

RG: I didn’t just read your book for this interview, I promise. But one thing that resonated with me from The Tao of Wu is the idea of having your island – a place to escape to and to breathe. Where’s your island right now?

RZA: My island is wherever me and my family are. That’s my island. Look, we live up in the mountains. You gotta go through two gates to get to us. I honestly got to say that’s my island now and when I come out to face the world I still got a lot of shit I deal with, a lot of headaches, whether it’s family or business, your legacy, the rights of your music, people sampling your music. But since I have my island I’m able to face the reality of whatever I gotta do, like Superman leaving the Fortress of Solitude and fighting the world. And if he didn’t have that I don’t think he’d be able to deal with the world.

RG: Do you notice if there’s any difference in your headspace or mindset of how you deal with everything now compared with 20 or 30 years ago?

RZA: The beautiful thing is that with maturity there comes a pacing and, instead of having the immediate reaction, which could be just dropping a bomb on it, there’s patience and a process to actually calculate the reaction. I honestly got to say that there’s days and times where the same way RZA would have reacted in 1993 is possible now. But an evolved RZA can look at that RZA from a distance and be like, “we don’t need him right now.” Maybe it was about ten years ago, it’s not publicly known, but I hit a bump. Just a bump in life, right? And my reaction to everything was miscalculated because the emotions had occupied so much space that the reactions would become emotional. Then I saw a picture of a nine-year-old version of myself. I actually put that picture at the end of my TV show, one of the pictures of myself. When I saw that picture, I remember the kid who never had a drink, smoked, had sex, lied, stole, nothing. I saw the eyes and I was, like, that’s me. All this other shit became me. You are what you eat. I ate all that bullshit. It helped me to readjust myself.

RG: RZA, one last request, where’s your head at now?

RZA: I’m driving in my Mercedes-Benz Sprinter. My assistant is sitting in the back. My wife is on my right side, chilling. I have an NPC sitting in front of me. Three bottles of water. All the shades are up, and we can see a broad landscape in front – mountains that resemble pyramids. The railroad track that travels from Los Angeles to Nevada. I’m seeing the sky is blanketed with clouds that all have some separation, so the sunlight is still breaking through.

- StylistJay Hines

- Art DirectorKat Beckwith

- GroomerAlex Hopki

- Set DesignLittle Apple Projects

- Digital TechColin Hoefle

- Photography AssistantEddie Saucedo

- Styling AssistantsGabriella Lane and Kelechi Njemanze

- ProducerJennifer Rovero At Nite Riot

- LocationHot Wheels Ranch