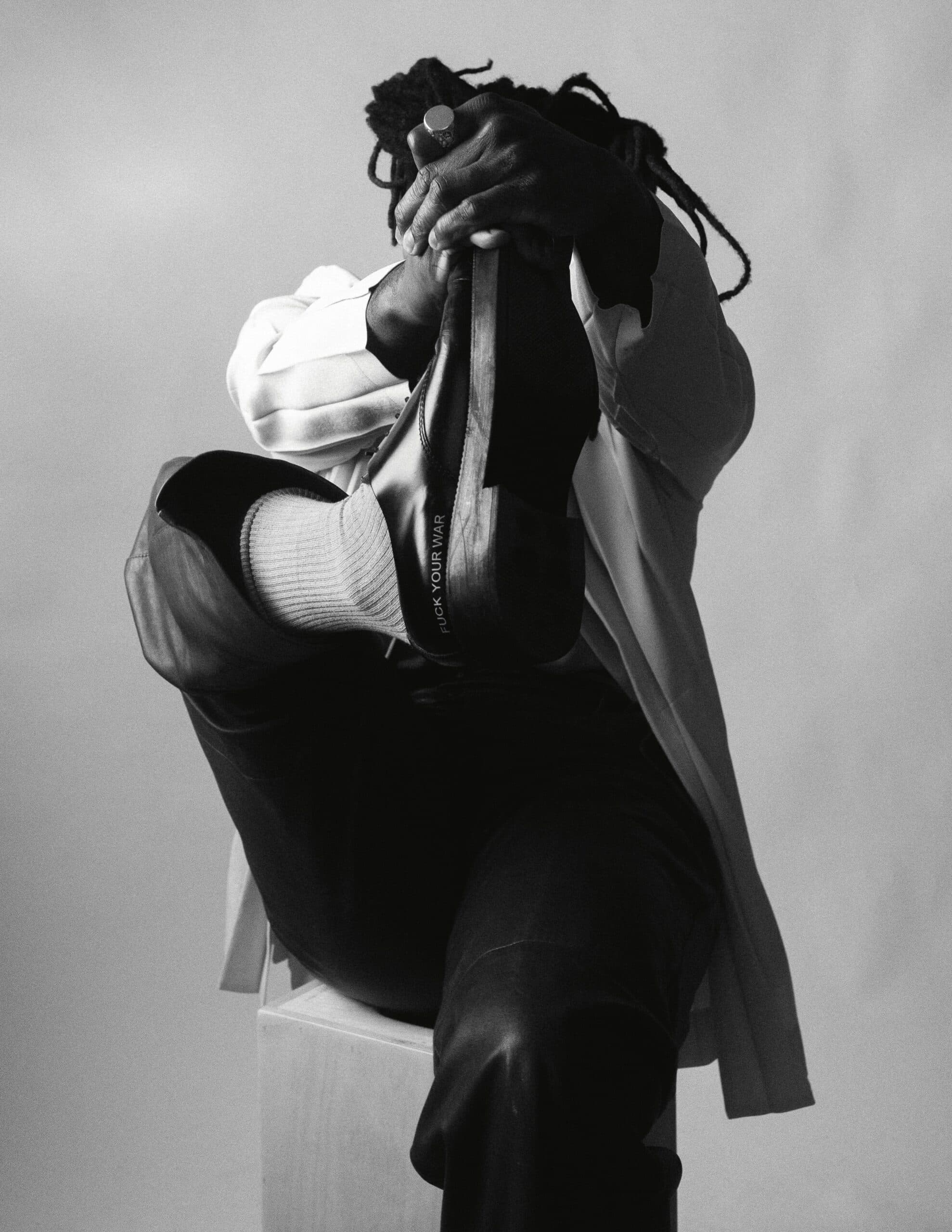

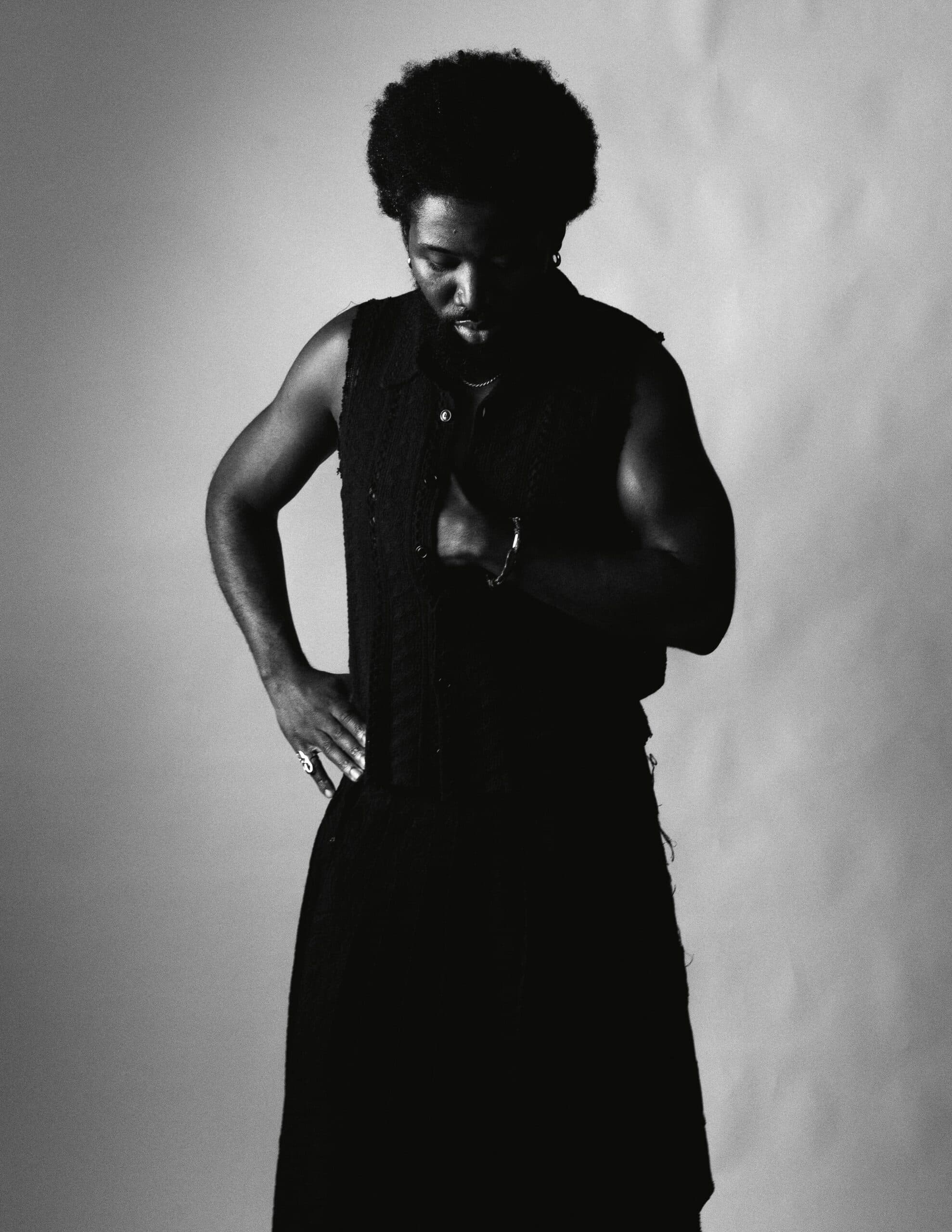

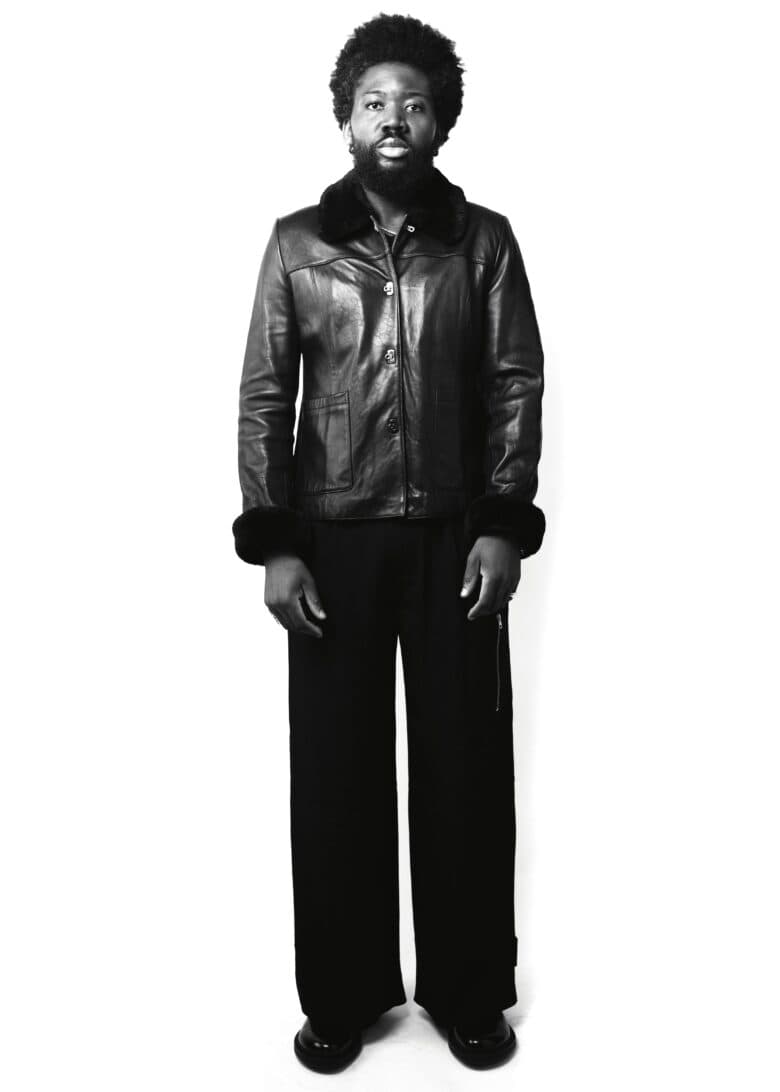

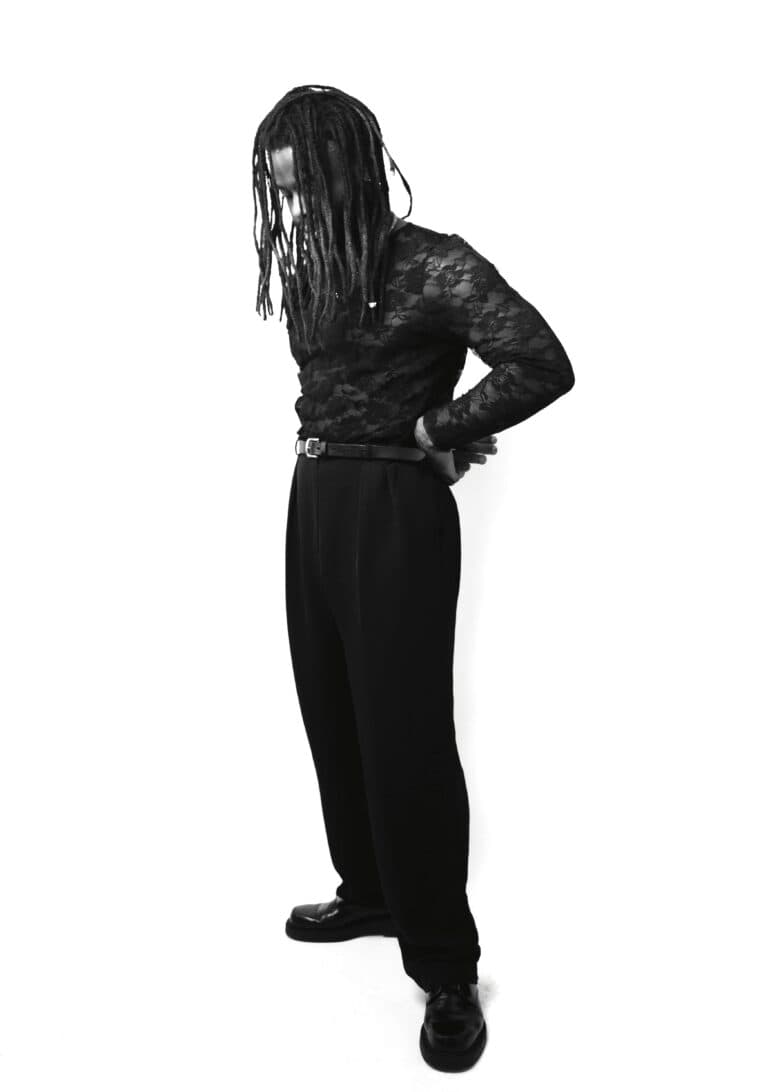

Young Fathers come as they are

- PhotographerAlex James-Aylin

- WriterNessa Humayun

Only a few times in a generation do you get a band like Young Fathers, a group so singular they defy categorisation. When I was thinking of ways to describe the Edinburgh-based trio, I was left blank – how do you pigeonhole a band that is purposefully enigmatic? Still, language is important, so here goes: Young Fathers are experimental, uninhibited, messy, political, joyful, chaotic, human, ecstatic, liberated, angry, transcendent, communal, misunderstood and, arguably, the best band performing in Britain today.

Graham “G” Hastings, Alloysious “Ally” Massaquoi and Kayus Bankole met as teenagers at a hip-hop night in the Scottish capital. Soon afterwards they were making music in Hastings’ bedroom, and at 15 were signed to a “traumatic” production deal whose fruits never saw the light of day. Miraculously they were able to reform as Young Fathers in 2008. The cynicism prompted by that chain of events has stayed with them. Despite their laurels, like winning the Mercury for their debut album, Dead, in 2014, Young Fathers have remained underdogs in the industry, a label they are simultaneously proud of and keen to shake off.

Their music is sprawling and amorphous, blending genres not limited to soul, hip-hop, rock, noise, pop and rap. Their references, too, are far-reaching: after trips to Ethiopia and Ghana, Bankole returned with shakers, drums and voice notes of kids crying to use in their acclaimed album Heavy Heavy, released last year. I saw them live three times in 2023, and their performances were ferocious, replete with chanting and ululating vocals. The crowd was whipped up into such a frenzy it felt like communion, especially after Hastings set off his war cry of “Fuck the Tories.” They’re not afraid to be provocative, but as they point out, they can’t not be political: Massaquoi himself was a refugee who fled war-stricken Liberia aged four. “We’re two black guys and a white guy – that’s always got to mean something,” he says.

When I speak to Young Fathers, it is shortly after the news they have been nominated for three Brits, including for Heavy Heavy. They’re incredibly generous with their time, and even more so with their answers. Instead of retreading old ground, they speak movingly about the impact mainstream success might have on them. It’s a complicated matter – how will a band that has only ever stuck to its guns and taken hits for calling out the UK’s warped political system, race relations, the royal family, and now the atrocities in Gaza, function with integrity within their increased visibility? Perhaps, as they always have: in a brotherhood that Bankole says has been built on “encouragement and celebrating and bringing out each other’s differences”. We dig further into it…

Nessa Humayun: You guys have been nominated for three Brits – congratulations! It feels like a major win for a band as political and genre-defying as Young Fathers. What would you want to come out of winning?

Kayus Bankole: It feels like the Brits have had a huge shift. I don’t know whether the people deciding things are confused and that’s why we’re nominated, and I don’t know why we haven’t been considered previously. Oh, and putting us down as an “alternative” act – that feels cheeky. Still, I think it’s positive.

Ally Massaquoi: In an ideal world I’d like to collect those three awards and that’s that. The creative industry likes to say “go against the grain” and “do your own thing”, but to me it sounds like platitudes. It sounds like they’re saying those things because it’s what people aspire to, but they don’t actually put that into practice. At the same time, the world doesn’t owe us because of the years we’ve put into our craft. I’m always conflicted because these awards mean everything and nothing at the same time. It’s definitely positive to be nominated because we’re a rare band – getting three nominations says that we can be mainstream too. And like Kayus said, we’re alternative to what? It’s just the music we make.

KB: I get the conflict. I’m trying to understand whether or not this is a testament that things are changing or whether it’s to make it look like things are changing.

Graham Hastings: For musicians like us, you just have to use the space. People need to be told what to like – if we use these nominations to get to more people, that’s fine, as long as we’re treated fairly. If the industry wants to use us for a shake-up, they can do it. If you look at pop history, it’s really slow to react, and the industry itself knows it’s become too stagnant.

NH: You met when you were 14 at a hip-hop night in Edinburgh – how did a musical bond form between the three of you?

GH: In Edinburgh there weren’t many options. You either had hardcore music or techno nights – I got jumped outside once, so it could be quite violent. The hip-hop nights were much friendlier. We bonded over the music that you could actually dance to – it wasn’t just fucking “put your hands in the air”-type stuff. We never really listened to the same kind of music, but there was always a unity in how we enjoyed music itself. The guys would come down to Mum and Dad’s and record in my bedroom. At the time, there was a lot of 8 Mile rap and hippity hoppity fucking shite. We bonded over making songs that were difficult and that’s what separated us from everyone else. The moment in which we met in those clubs still lives with us as a lesson in how to enjoy music – they were dark, dingy, sweaty clubs and there were people who were actually dancing and not just standing against a wall. That made an impression. Expression wasn’t really championed when I was growing up in Scotland, but those nights were a whole new thing. After I walked into those clubs, I never looked back.

NH: It must have felt like a dream when you were signed at 15, but that wasn’t the reality. What was that period like?

GH: We were signed as minors, and our guardians at the time of the first deal were told that we were going to be a superstar boyband and go on Top of the Pops. We were put into a certain situation and I think we’re extremely lucky to have been able to come out of that and stick together. We got to see the back end of the industry and the horrible shallow bits without having the one-hit wonder that can break some people – it gives them this huge burst of a certain

kind of lifestyle, but nothing ever comes from it because the creativity isn’t there yet. That would have soured our careers, so we went the other way. Making Tape One and Tape Two was where we cut our teeth.

NH: After your third album, Cocoa Sugar, at one of the highest points of your careers, you took five years off. A lot happened during that time – Graham, I know you had two kids. Why did you need that time and how did it influence the making of Heavy Heavy?

GH: We spent the best part of ten years working pretty intensively, and you do lose sight. The three of us have a thirst for trying to make music that you’ve never heard before. We’re always trying to make a sound, song, or idea that hasn’t happened. With Heavy Heavy, we didn’t really speak that much about anything in the studio – we just got straight to it. Quickness is really vital.

AM: That break period wasn’t that hectic for me. Covid was around, so I wasn’t seeing anybody because everyone was scared and fighting over toilet roll. We’d been touring so much that it was nice to chill with family. I started to really enjoy being at home with my mum.

Like I say in [the Heavy Heavy track] “Geronimo”, it really is about being a better son, brother and uncle – the simple things. You’ve got to appreciate the people who are keeping the world together in a nuts and bolts way. Sometimes, for me, music loses its magic and I need to find it again.

KB: Did I know how to walk into this environment of creation after being idle for a bit? The answer was yes, and it happened very quickly. On what Graham was saying about trying to make music that we haven’t heard before

– personally, it’s not something I try to do. But I think all three of us naturally zone into the bits that usually get ignored – the intricate emotions that you don’t really talk about or the sounds that you bypass.

GH: We don’t like when anything feels too formulaic. There’s this cringiness that occurs when it’s too close to something that already exists. I wouldn’t say that it’s anti-formulaic because we still love writing short songs with hooks.

NH: Is that why Heavy Heavy ended up being just 30 minutes? The album has so much propulsion that there almost seems to be a dramatic central argument. Did you have to drop a lot of great stuff to make it so tight?

AM: Absolutely. When we were working on it, the songs were too intense. We wanted to have six or seven songs, like albums did back in the day. We had a playlist with different variations of the album, but we found that when we added certain songs that each of us wanted, it took the album somewhere else and lost the communal aspect. We wanted “Shoot Me Down” as a starter for so long, but it was just messing with that flow. As soon as we let it go, and used “Rice”, the whole thing opened up. You have to risk stuff to allow the good things to follow. With great art or anything that makes you feel something, you want to go back to it… I think that’s what this record does.

NH: It’s interesting because the more I listen to Heavy Heavy, the more I see it as a celebration. One line that has stayed with me is “Brush your teeth, wash your face, run away” – I’ve been trying to figure out what it means since I heard it. Sometimes it feels like a battle cry and sometimes it’s an invocation to give up. What does it mean to you?

AM: It’s preparation for the unknown. What’s the thing that unites us all? Brushing your teeth is renewal, something so simple like washing your face is a routine. It’s these sorts of things that link people together as a sort of glue – it’s a precursor to something. I was trying to put in a reference to the mundane and my experience of being at home during that time and seeing things in a more magical way, the ordinary into the extraordinary.

KB: Just wash your hands, clean your ass and get on with it. Wash your ass!

AM: Yeah, wash your ass!

GH: That’s really positive. I thought the opposite – it’s purely about Brexit, man! For me, the end bit is like turning a blind eye. Just ignore it because no one’s got any time to deal with anything and secretly, or not so secretly, everything’s falling apart. It’s like, I’m just going to keep myself to my wee self.

KB: To me, it’s an attitude thing. The whole track embodies that “just get on with your own business” attitude. Everyone’s got their own interpretation though.

NH: You’ve spoken about how you don’t get the radio plays you deserve and why that’s partly because you exist in an industry that can’t define what is purposefully enigmatic. Do you think there’s a reticence from the industry to recognise you, in part, because you’re punkish, anti-establishment and stand up for things, like Palestine?

GH: Yes is the answer, but I suppose we just do what we think is right. The idea of making music that we don’t enjoy is not for us, and the idea of not standing up for the things we believe in is not for us. It’s laughable to us that we might be a problem. At times we’ve been so frustrated by how things work – we feel like we’ve made a pop song for everybody and then realise that there’s people in the rooms of every big media establishment that decide what the masses get and what they don’t. Why is someone like that deciding that this is too grating, aggravating, or too tough for people? People are always making decisions on whether your music fits on a playlist, or if your styling fits, or if your performance fits… Or if your accent fits.

KB: The more I think about it, it’s like, it’s dangerous for who? Who is it dangerous for?

GH: It’s the danger of offending someone. Everything relies on fucking advertising money and numbers, and they view it as a huge risk to lose audiences. We can’t upset them even just a little bit.

KB: If that’s the case, I would happily remain dangerous.

NH: I’m curious about how you’ll react to going even more mainstream – your views and morals could, sadly, end up closing doors for you. It’s a difficult question, but would you be happy for those doors to close?

KB: We’ve been doing it for fucking God knows how long, and our stance on humanity hasn’t changed. We have a huge affinity for fairness in every aspect. It’s part of our make-up.

GH: It’s just sad that having these opinions is considered dangerous – that saying “Don’t bomb children” is a point of friction. How blind are we at this point? Looking back to us losing the deal when we were younger, I’d say the doors have always been closed. We’ve learnt to enjoy ourselves in our own space, and we never wanted the doors open more than we needed. The priority is always going to be the songs that we want to make, or the things that we want to talk about, or the way we want to perform. What are we losing anyway? There’s nothing to lose that we would gain by compromising our values. What we talk about is reality and it’s not going to stop.

AM: It’s a funny one. I agree with all that, but at the same time, I’m still human. I don’t want doors being closed. At a surface level, they’re wrong for that, and we’re right. You know that’s the case, but everybody’s telling you that it’s not. You start to second guess yourself. If you have a family and other mouths to feed, it becomes even more complicated. Money gives you options, freedom, the luxury to actually pick and choose what it is that you want. That’s what being a human is. You have to make a decision and stand behind that. Are you willing to do that? The people who can afford to do whatever they want don’t care. Their ideals are different from someone from a working-class background. They can afford to close doors and not think about whether they’ve taken food from someone else. There’s a lack of space for our band and our ideas, so we’ve had to work hard. It’s that working-class mentality. It’s very easy to say we’re doing the right thing, fighting for the downtrodden. At the same time, we’re humans who get tired. That’s the overriding thing – we can all say “Fuck the Tories” but you have to look at the bigger picture too.

KB: I want to get to that place where we have the luxury of saying “no” more.

GH: You say “no” a lot.

KB: Not as much as I want, God damn it! We do say “no” a lot, but let’s not be disillusioned – it’s a luxury. I’ve got bills that need to be paid.

- PhotographerAlex James-Aylin

- WriterNessa Humayun

- StylistDetroit Law

- Art DirectorKat Beckwith

- Make-up ArtistMV Brown

- Hair StylistReece Phimister