SJ Fuerst: The American artist bringing surrealistic pop art to the island of Malta

- WriterNessa Humayun

I am standing in the airy, Gozoan home of the artist SJ Fuerst. Carved into white rock and dotted with sky-lights, it exudes a serenity that is emblematic of this quieter side of Malta — just a ferry ride away from the bustle of the mainland, Valletta. Gozo is nestled up to the sea, you can see primary-coloured boats bob peacefully year round, and the buildings are sun-drenched and sandy — it must be an idyllic place for a painter to work, I remark. It is, Fuerst concedes, but her art is anything but reminiscent of her bucolic new home.

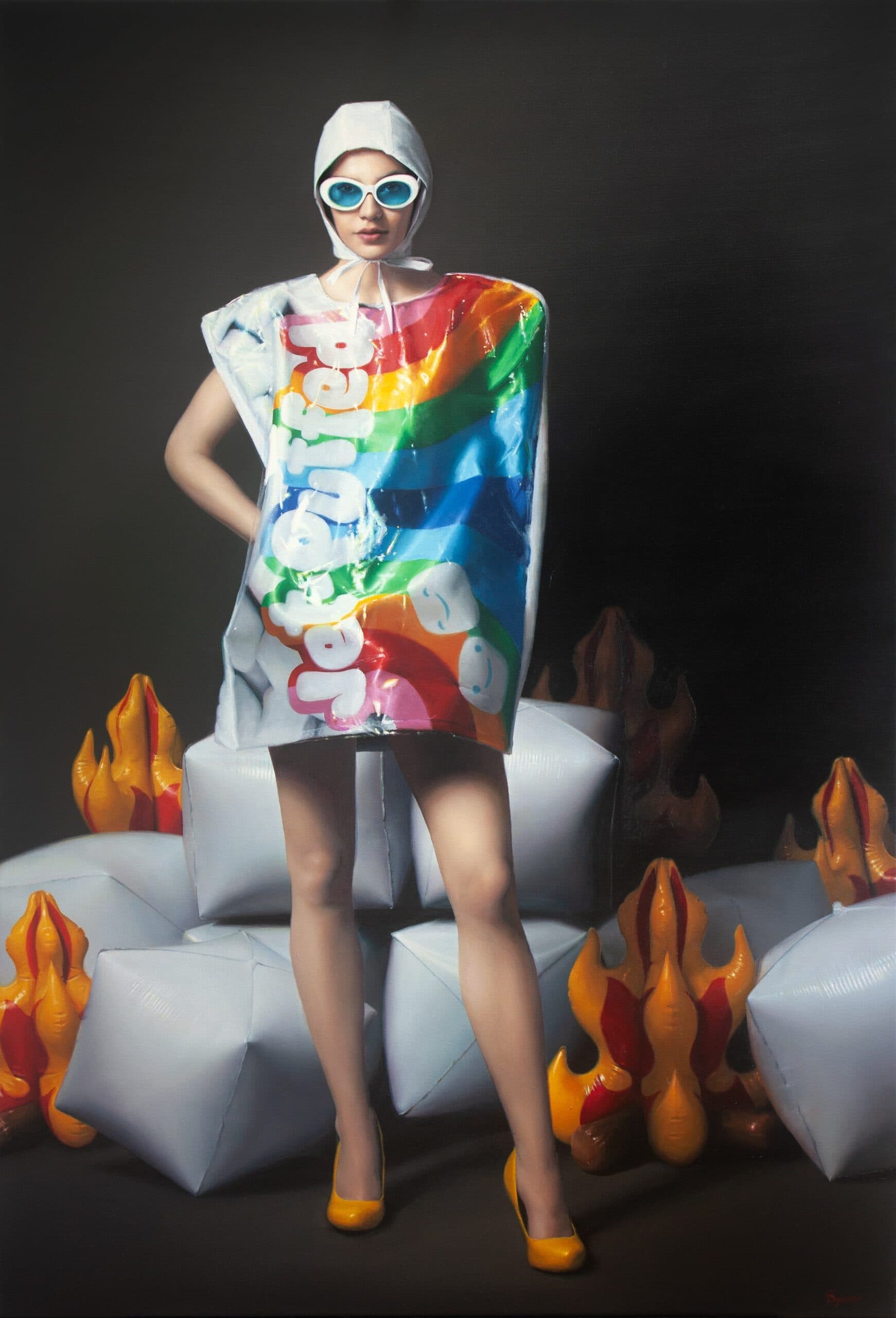

The figurative painter, who hails from New England, US, combines classical portrait painting with neo pop art to create hyper-realistic, surrealist works that certainly packs a statement. Bursting with colour and innuendo, she paints on canvases, but is also a fan of nostalgia-inducing mediums like children’s board games and floppy discs.

Peering around her home, which she shares with her partner, the acclaimed oil painter Luca Indraccolo, is a veritable treasure trove of delights. At first glance, their coffee table seems to be full of sweet boxes, marshmallows and lollipops wrapped in cellophane. They look good enough to eat but are, in fact, life-sized artworks created out of clay, resin and cardboard. On them, Fuerst has painstakingly painted tiny images of the models that adorn her canvases. Then, in another room, she unveils a fireplace made to roast the aforementioned marshmallows; it lights up and all, at first glance you would think it were real.

Fuerst and Indroccalo have been working in Malta for several years now, after relocating from London just ahead of the pandemic. The artist, who has a life-long love of pop art and its famous purveyor, Andy Warhol, began her career at New York’s Pratt Institute School of Art and Design and later, the Florence Academy of Art and the London Atelier of Representational Art. In the years since, she has been named by British GQ as one of the 15 best artists working today,

On that, you can’t miss the giant canvases that adorn their home. Fuerst works with models and inflatables — the house is littered with the latter, giant flamingoes, watermelon slices and all — and renders them into photo-realistic pop-art paintings. They’re tongue in cheek, and occasionally suggestive (Fuerst shows me a board game on which she painted giant, purple aubergines…) “My mom says she always feels like there’s something sinister lurking just off the canvas of my paintings. But that’s life, I think,” she comments with a laugh. “I do want the overall emotion to be happy, but if some people look at my work and they’re like, ‘ooh, that’s really messed up’, I also don’t mind that. It makes a more nuanced piece of art.”

These are decidedly adult works — a wink to the viewer, an invitation to look deeper into influences like capitalism and the male gaze; it’s not all sugar, spice and everything nice, as you may initially think.

Fuerst will be exploring all this at her upcoming exhibition, Gimme Some Sugar, at the Malta Society of Arts, now helmed by the curator Gabriel Zammit. Below, HUNGER chats to the artist about her solo show, her pop art roots and some of the more subversive undertones to her vibrant pieces.

Nessa Humayun: A few years ago, you moved over to Malta. It’s an environment that’s really different to your native Connecticut, and London, where you and Luca lived previously. How has this small island inspired your work? Pop art was obviously birthed in America, but now you’re somewhere that’s so European, so different…

SJF: It was when I moved here that I first started using nature printed backdrops in my work. I partly chose to move because of the transition from city to nature; wanting to be in the countryside and being a bit more secluded and away from the hustle and bustle of so many people. As you can see there are still a lot of people here, but it’s less than in London. The show after this one is going to explore that shift back to nature more, but this one is all sugar and candy, which I guess isn’t super Maltese. They do have amazing desserts here…

NH: When did you first discover pop art? Did it inspire you right away?

SJF: Initially Warhol; I loved his soup cans and the bright Marilyn Monroe prints. I also love the idea of popular subject matter; they resonate with more people, you don’t need an art history background to look at them and be like ‘I get it!’. And as an artist, you want as many people as possible to look at your work and be like, ‘I understand’ or ‘I connect with it’. That’s what I loved about his work — we always understood the Campbell soup reference because we had it in our cupboard.

NH: In that vein, you’re very inspired by certain objects. Did it come from childhood? There’s definitely an element of play in your work that can be harkened to nostalgia.

SJF: Definitely, it’s because I tend to… What’s the word when you make inanimate objects into people in your head? I anthropomorphize things. I do that with everything, so I feel very strong connections with objects. The floppy disks were the first things I painted on because they popped up when I was sorting things out. I realised that I missed them. It’s like, ‘oh they’re obsolete now’, but I thought it would be so nice to have a way to still interact or play with floppies. So I was like, ‘let’s paint on them’. And it was also an excuse to work small, because I wanted to do some smaller things. But it was about enjoying the actual objects. It’s kind of like posterity. You’re keeping it alive.

NH: A lot of your work is a contrast of new and old. Why do you think that works so well?

SJF: Yeah, I guess even our house is sort of like that. I’ve always loved figurative painting in the romantic, classical style. They have all the correct anatomy and they’re so smooth and lovely, but then if you only paint like that, it looks like you’re trying to make work that could have been done 200 years ago. You can use those skills but make it relevant to today and interesting to what people’s tastes are in contemporary life. It’s nice to use the classical style but paint on really cheap, mass-produced contemporary objects.

NH: How much do you think that is inspired by your own American-ness?

SJF: A lot. We’re a shopping family. In the suburbs, there’s not too much to do, so growing up you’d just go to the mall with friends. Just to sort of walk around. Not even because you needed to shop, it was just the thing to do. Whenever I go into any store, I have to touch everything. Seeing the bright colours and how beautifully designed everything is, I find it inspiring. I think packaging is also beautiful; all these amazing graphic designers and a lot of research goes into making a box of candy as visually appealing as possible. Packaging definitely works on me — I’m easily suggested.

NH: I guess it plays into this idea of consumerism, right? I noticed that in your women. They’re very beautiful and conventionally attractive. Where do they come from? Who are they?

SJF: Yeah, they are. They’re fashion models. When I first started, I was working with friends, but then I began working with professional models because they’re more comfortable being photographed, and that made a huge difference for the paintings. It’s subtle, but there’s changes in expression and body language that we’re so good at reading. You know, if someone’s confident, if someone’s comfortable, if they’re happy. I really don’t want a painting where you can sense that she didn’t want to be there.

NH: Do you paint them in real life or do you use photographs?

SJF: Now, I work from photos. We trained exclusively through life drawing, so the poor models would stand there for three hours a day for six weeks. You’d always try to talk to them so they wouldn’t fall asleep. It was amazing to train in that way because now I know things to look for: how the light reacts and how the shadows behave, because the photos do flatten things out a bit. But now I couldn’t put a model in, you know, a giant heel, and ask her to stand there for eight hours a day for the next six weeks. I’ll come up with the concept for the painting and I’ll buy all the props and costumes — everything’s real. But then I’ll contact a model agency to see who would be up for it. They’ll come over and I usually do three costumes per shoot with the model, and we take about 700 pictures. I’m always so nervous before a shoot because it feels like there’s so much riding on it. I’ve normally had the image in my head for about three years.

NH: How is it with you and your partner both being painters?

SJF: I think it’s lovely. If one of us is having a day where something feels off in a painting, having a fresh set of eyes come in and look at it is amazing. It makes such a difference, especially since we’ve had the same training. Sometimes our creative ideas don’t align, so we don’t really conceptually brainstorm together, but we run ideas past each other. We just run with it. It’s art.

Luca : People ask if we have competition. Never. It’s absolutely important that my paintings look like my paintings and SJ’s paintings look like her paintings. If we had more creative input into each other’s work, it might start to pollute the pure art that you see.

Nessa: When it comes to the small objects, how is it kind of working with the textures? Is that a real lolly, for example?

SJ Fuerst: I made it out of resin. The other foods are made out of clay, and the candy boxes are real cardboard.

Luca Indraccolo: But even [the candy boxes] you prepare. Because otherwise – what happens if you paint on cardboard – the oil gets absorbed. So you seal it and paint over it.

SJF: Painting on the resin was difficult. I would do a first pass in acrylic, just to give a layer of paint that sticks a bit better, and then I’d start working on it with the oils. But with something that tiny, I have to try and do all the little faces in just two days. If the paint starts to build up too much, it just gets really clumpy and it hits a point where it’s getting worse rather than better.

NH: That’s insane. It looks like it’s been printed.

LI: Yeah, painting something on like that… I swear to God, if you’re half a millimetre off, you know, one eye’s over here, one eye’s over there.

NH: It’s a lot of work for something so tiny, but it must be so satisfying once it’s done, right? You’ve got this perfect little thing.

SJF: Yeah. And, I mean, two days compared to eight weeks feels fast. I can just tick those off. But that’s just how slow I paint. You would think you could paint two square centimetres in a lot faster than two days.

NH: With the hyper realistic stuff, there’s the idea of kind of perfection. That if you’re creating pop art, it has to be perfect.

LI: It’s a funny mix, isn’t it? Because it’s pop art, but then it’s painted like the old masters. That’s how she is in real life too. Like, she made Damien Hirst’s encrusted skull, but she used a Lego skull, encrusted it with diamonds and made a purse out of it.

SJF: It’s just so nice having something that’s creative to do, but that doesn’t have the pressure of it eventually going on sale. I don’t feel like it has to be so perfect. That’s why I love doing the little purses, because it’s just a release of the perfectionism that I put into my work. I’m always trying to move away from that because whenever I’m like ‘this has to be perfect’, it ends up going badly.

NH: What’s interesting about your work is the play between what’s real and what’s fake. Could you elaborate on that and where it came from?

SJF: I do like making fakes. It sounds like I’m selling fake IDs or something, but I just mean that it’s fun seeing something and trying to recreate it. It must also be a bit nostalgic. I love making the lollipops because I have such strong memories of coming out of the doctor’s office and seeing this basket of lollipops that I would take [one from]. And I love the challenge of trying to make it myself. Like, ‘could I make a lollipop?’ I’m obsessed with marshmallows too. I just had a happy day with my clay, trying to make it look as much like a toasted marshmallow as possible. We were roasting a bunch and I was taking lots of pictures and studying the texture and how they’re shaded. It’s just problem solving, which is fun.

NH: You could put anyone on your artwork, but you choose women and people. Is it because they’re the ones who interact with these objects?

SJF:I think so, yeah. I’ve always been drawn to figurative art because it sort of shows you how to connect with it. I think about this a lot with my big paintings. If it’s just a painting of an inflatable zebra, then you don’t see yourself in it as much as if you see another figure. You identify with the figure, and it makes the painting more relatable. You can identify with the expression or the mood, or a lot of people will see someone they know in the portrait.

NH: A lot of your work seems quite happy. Is that a reflection of you?

SJF: If I’m going to be making something and looking at it for so long, I want people to feel happiness when they look at it. I don’t want to make something that makes you feel like, ‘ew’. I don’t need to put more of that in the world. Like, let’s focus on something that people would want to look at. Or at least that I would want to look at.

LI: Sometimes you also make more of a social statement. With The David, there was a whole political thing. It was cardboard cutouts out of old paintings from the Bible and stuff. What I’m trying to say is, yes, they’re happy, but there’s always a bit of a girl power message.

SJF: My mom says she always feels like there’s something sinister lurking just off the canvas of my paintings. But that’s life, I think. I do want the overall emotion to be happy, but if some people look at my work and they’re like, ‘ooh, that’s really messed up’, I also don’t mind that. It makes a more nuanced piece of art, I guess.

NH: How much do you think your feminism informs your work?

SJF: A lot. I’m aspiring to that confidence of, like, ‘this is me, I’ve got this’. So with the women in my paintings, I make sure they’re always in control. Even though they’re dressed in ridiculous things, they’re happy to be there, and they know what they’re doing. They’ve got this. Most of the models actually do love their costumes. They do! That’s what I love the most! They really have fun. I’m always really looking for models with that sense of knowing who they are. Like, they’re stunningly gorgeous, but that’s not as important as the attitude within the painting. I mean, that might not always come across. There are probably a lot of people that just see the beautiful woman. I’ve had some people – because I go by SJ and really try to keep my gender offline – find out I’m a woman and make my art completely about the feminist angle. When people assume I’m a male, I’ve had so many complaints. Like, ‘oh, he’s such a misogynist’. It’s so funny how it can be read so differently.

SJ Fuerst’s Gimme Some Sugar will run from May 2nd – 23rd at the Malta Society of the Arts