The very existence or presentation of authenticity – so often not physical, but mental – is a rejection of the binary and heteronormative world we find ourselves grasped by. We know this as queer people. And so many of us face the uncomfortable and often untruthful reality on a daily basis. But within the struggles and refusal to simply tone ourselves down through fear that others can’t handle our greatness there is a grouping of spaces. A place, space, shop, gathering or even simply a location with no roof where we gather to live together.

It’s a concert that, to others, seems small but to us so mighty. But to get to a place where these locations are a thing of the present and reality, rather than just in our fantasy, takes time, progress and so often the lives of others. It’s the battles that are intertwined with the history of the queer movement. It’s the fighting against oppression to have a place of our own.

And it’s the ordinary lives of ordinary people doing extraordinary things that make these spaces possible. A reality. A real place of love. A place where love is the only light.

Captured by the photographer Jordan Rossi, some of the figures whose voices have brought us to this day discuss progress, problems and the beauty of possibility with HUNGER. It’s a snapshot of how the often small acts of resistance can lead to a world of great change.

This is 21st-Century queer liberation – told by those who got us here.

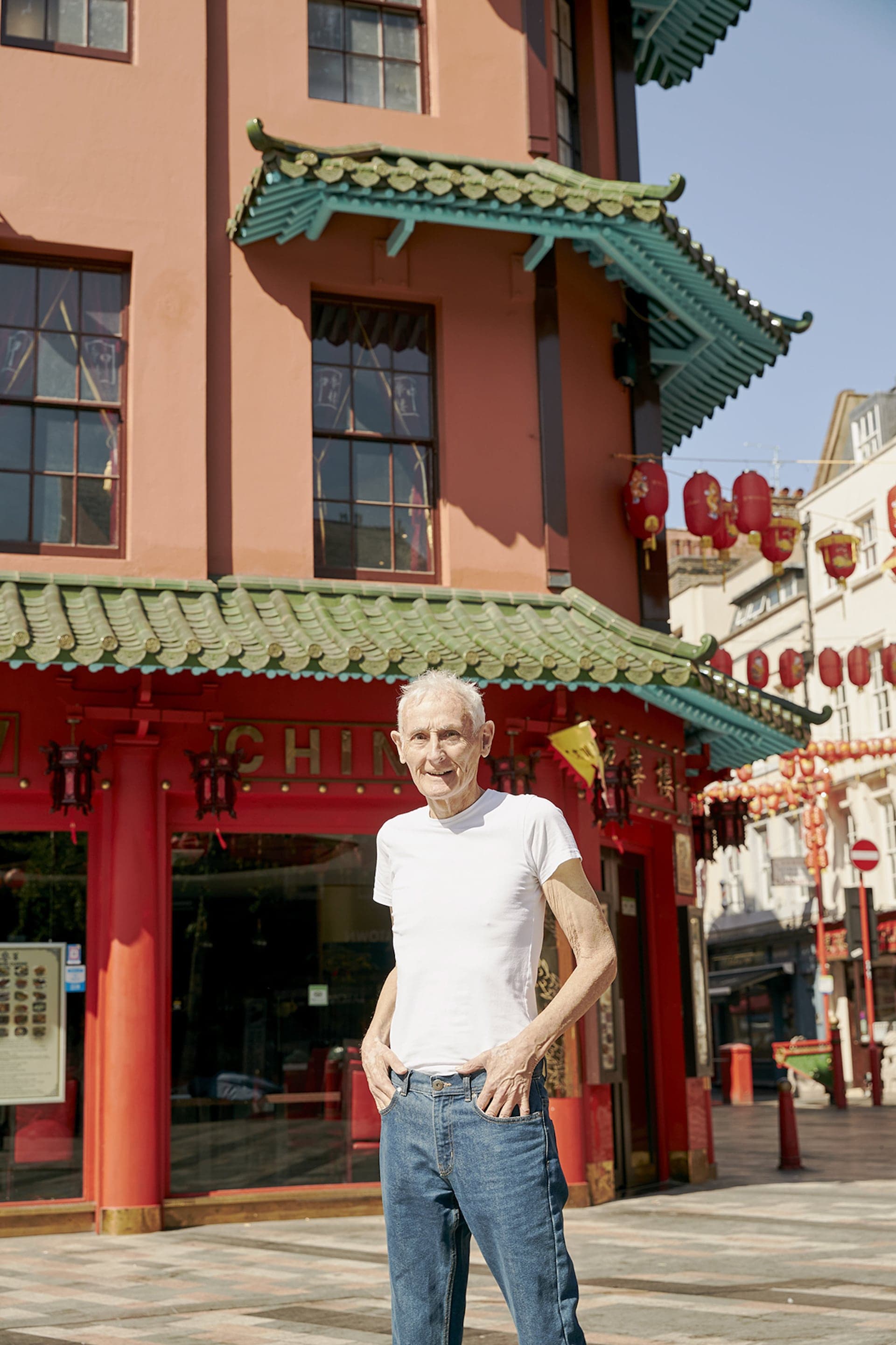

PETER TATCHELL

LGBTQIA+ RIGHTS AND HUMAN RIGHTS CAMPAIGNER

William J Connolly: Who is Peter Tatchell?

Peter Tatchell: I’ve been an LGBTQIA+ campaigner and human rights defender since 1967. Protest has played a central role in all the gains the LGBTQIA+ community has won and I’m proud to have been part of it. I’m currently the director of the Peter Tatchell Foundation.

WJC: What’s the greatest and heaviest threat to the progression of LGBTQIA+ rights in 2021?

PT: Organised religion and the far right, although the UK government comes a close second with its failure to reform trans rights and ban conversion therapy.

WJC: What is authenticity to you?

PT: Swimming against the tide, being true to my conscience and standing up for freedom and justice – regardless of what others say or do. I’ve often been ahead of my time and gone against the prevailing consensus on issues such as LGBTQIA+-inclusive sex education in schools, in 1971, gay equality in communist countries, in 1973, comprehensive equality laws, in 1978, and same-sex marriage, in 1992.

WJC: What does gay liberation mean to you?

PT: We cannot be liberated without transforming society. LGBTQIA+ equality within the flawed straight status quo is not liberation. Who wants to be equal in a fundamentally unjust society? I want a better, fairer society for everyone. The ultimate goal of LGBTQIA+ liberation is to make homophobia, biphobia and transphobia history. We should aim to secure this goal alongside the eradication of poverty, racism, misogyny and all other forms of oppression.

WJC: Where is the space or place you feel most authentic?

PT: Taking direct action in the streets for LGBTQIA+ liberation. I’ve been involved in over 3,000 protests and been arrested 100 times but have only one conviction. It was for the 1998 Easter Sunday protest against the homophobic Archbishop of Canterbury at that time, George Carey. I was convicted under the Ecclesiastical Courts Jurisdiction Act of 1860, formerly part of the Brawling Act of 1551, which has a blanket ban on protests in churches.

WJC: How progressive would you say the LGBTQIA+ movement has been?

PT: The LGBTQIA+ movement has, overall, been an inspiring and successful force for our emancipation. However, we need to do more to uplift trans, Black, female, disabled and working-class LGBTQIA+ people. And our movement needs to have a stronger focus on global solidarity with LGBTQIA+s in the 69 countries that still criminalise same-sex relations.

WJC: While every protest is important, which one had the greatest impact on the person you are today?

PT: The US protests against the 1963 racist bombing of a Black church in Birmingham, Alabama, where four young girls were murdered. I was only 11 when I heard about the bombing and the protests against it. But I was moved to follow and support the Black civil rights movement. When I began my activism four years later, that movement became my template. I adapted its ideals and methods to my own campaigns. They’ve been my activist lodestar ever since.

WJC: Which protest are you most proud of – and what effect did it have?

PT: My two attempted citizen’s arrests of the homophobic Zimbabwean dictator, Robert Mugabe, in 1999 and 2001. They got masses of media coverage and thereby raised global awareness about his human rights abuses. But they also left me with a bit of brain and eye damage. I have no regrets. Both protests made a huge positive impact.

WJC: You attended the first UK Pride march in 1972. Can you describe what that moment and day was like?

PT: It was exciting and a bit scary. Only about 1,000 people marched. Back then, most LGBTQIA+s were closeted. We were swamped with police. It felt quite intimidating. But we were defiant and determined to make our point. Public reactions varied, from hostility and abuse, to gawping disbelief that LGBTQIA+s would dare show their faces. Even so, much to our delight and surprise, about a third of the public were supportive. That emboldened us to repeat Pride the following years.

WJC: From your experience, how effective has the LGBTQIA+ movement been in changing laws in the UK?

PT: Until 1999, Britain had the largest number of anti-LGBTQIA+ laws of any country in the world, some of them dating back centuries. By 2013, with the legislation of same-sex marriage, all those discriminatory laws had been repealed. That was the fastest, most successful law-reform campaign in UK history. My huge thanks to the thousands of LGBTQIA+ people, and straight allies, who helped us win these victories.

LADY PHYLL

CO-FOUNDER OF UK BLACK PRIDE

WJC: Who is Lady Phyll?

Lady Phyll: I’m a queer Black African warrior woman. Mother. Lover. Friend. Sister. I am a woman of layers and complexity. I’m an activist by blood and by choice. I am an example of joy, persistence and tenderness.

WJC: How would you describe what UK Black Pride is?

LP: It’s Europe’s largest celebration for LGBTQIA+ people of African, Asian, Caribbean, Latin American and Middle Eastern descent. We produce an annual celebration during Pride Month, as well as a variety of activities throughout the year in and around the UK, which also promote and advocate for the spiritual, emotional, and intellectual health and wellbeing of the communities we represent. UK Black Pride is a safe space to celebrate diverse sexualities, gender identities, cultures, gender expressions and backgrounds and we foster, represent and celebrate Black LGBTQIA+ and QTIPOC culture through education, the arts, cultural events and advocacy.

Importantly, UK Black Pride promotes unity and co-operation among LGBTQIA+ people of diasporic communities in the UK, as well as their friends and families. In the words of Audre Lorde, “There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives. Our struggles are particular, but we are not alone.”

WJC: What’s the greatest and heaviest threat to the progression of LGBTQIA+ rights in 2021?

LP: It would be a mistake to look at LGBTQIA+ rights in 2021 as separate from every other year. Everything the LGBTQIA+ community is facing, including a rise in hate crime, including the ongoing transphobia that runs rampant in this country, is a result of a thin and exclusionary approach to LGBTQIA+ rights in this country more broadly. If we don’t tackle institutional racism, if we don’t educate people properly, if we don’t allow trans people the healthcare and autonomy they deserve, if we don’t fight against a healthcare system that continues to disregard Black life, no one will enjoy the freedoms that are allegedly so foundational to this country.

When the marriage-equality movement was happening, nothing was being done to tackle homelessness or racism or transphobia. And so it is perhaps our approach to LGBTQIA+ rights that is the threat. Our politics has to be one that is intersectional, that accounts for the many ways oppression is meted out to so many in this country. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again – there is no liberation for any of us without liberation for all of us.

WJC: Tell me about a place or space where you feel most authentic?

LP: I don’t care for “authenticity”. It’s very subjective. What’s authentic about me to you might not be what’s authentic about me to me. What’s authentic to me might be threatening to you. I feel most Phyll, most myself, most empowered, in two places – at UK Black Pride and at home with my daughter.

WJC: While we see challenges, we also see progress. How progressive do you feel the LGBTQIA+ movement has been?

LP: It’s not progressive enough. Many in our movement still don’t understand intersectionality or how to build an intersectional movement. We see a lot of people building brands and not having much impact. At the same time, we have some real fire starters, who are out there doing the work and working very hard to ensure LGBTQIA+ people, Black people and LGBTQIA+ people of colour have our rights. I’m thinking of Ryan Lanji, Tanya Compas, Chloe Cousins, Emmanuelle Drews, the volunteers at UK Black Pride – who do lots of work in community outside UK Black Pride – as well as elders like Ted Brown and Marc Thompson, who continue to share their wisdom with a new generation.

WJC: What does gay liberation mean to you?

LP: I think gay liberation is the wrong way to look at it. The movement for LGBTQIA+ equality relies upon its ability to interact meaningfully with other movements for equality and liberation. How do we stand up for refugees and asylum seekers and for young Black boys who are excluded from school? How do we call in, call out and stand against Islamophobia and the deaths of Black women in maternity wards across the country? What’s our position on the rights of the imprisoned, on homelessness and on education?

A great example of what our movement could look like is the collaboration and solidarity between the Black Panthers and the STAR movement, led by Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P Johnson. They knew in the 1960s that LGBTQIA+ liberation wouldn’t happen without Black liberation. And I think of people like Olive Morris, who stood up and spoke out using an intersectional analysis before intersectionality was defined. We need much the same now. Across time, we have the references, the knowledge and the work to build on. Our task is to bring our movement back to its intersectional essence.

TED BROWN

GAY LIBERATION FRONT ACTIVIST

WJC: Who is Ted Brown?

Ted Brown: I’m a Black gay activist who would like equality for everybody.

WJC: What’s the greatest and heaviest threat to the progression of LGBTQIA+ rights in 2021?

TB: Complacency and corporation. When I think of what we’ve achieved with our rights since Stonewall, they could still be taken away from us. And this includes ignoring the threats posed against LGBTQIA+ people in places like Poland and Hungary. They need our support, because if people succeed in attacking us there, then the same will be brought back here to the UK – and we may find ourselves fighting another Section 28 in Britain.

WJC: Where do you feel most authentic?

TB: There are two places that I have. One is in New York in Sheridan Square, where I joined early Gay Liberation Front marches. I think that was the 1972 or the 1973 march. And the other is in London’s Greenwich, at the Trafalgar pub, where we used to hold meetings as what was called the Kiss Me Hardy group. And that’s because the Trafalgar had a picture of Nelson, whose last words famously were “Kiss me Hardy”. So we held meetings there for the LGBTQIA+ group underneath that picture, which unfortunately I think they might now have moved. I felt very at home there because it was also close to the first place that I ever came out, which was to my mother when we lived in Greenwich, in Delany House in Thames Street.

WJC: How progressive do you think our movement is today?

TB: From my experience, it’s been inspiring how quickly the LGB community has taken on support for trans people. For years, they were considered peripheral or superficial to our movement, but in fact they are probably challenging the heterosexual norms more than even lesbians and gays are. I think it’s wonderful that we are working together to fight against the transphobia that’s surrounding us at the moment.

WJC: We talk of authenticity, but what does the term mean to you?

TB: It means realising who you are and pushing for recognition of your definition of who you are, which is why I think the trans movement is so critically important to us all.

JONNY WOO

DRAG QUEEN AND OWNER OF THE GLORY, DALSTON, LONDON

WJC: Who is Jonny Woo?

Jonny Woo: It was a nickname from school and became my stage name and, to an extent, a persona. The outrageous, provocative, show-off, dressed-up side of me. People still call me Woo off stage so it’s still basically who I am, toned down, regular, blending in. I guess I’m becoming more comfortable with who I am and that comes with age. So when on the stage, the costumes are the character, and when off the stage you get much less of the “Woo”.

WJC: What’s the greatest and heaviest threat to the progression of LGBTQIA+ rights in 2021?

JW: Gentrification or accelerated urban development is a huge threat to our spaces, our bars and our clubs. We have the right to places to mix, dance, kiss and be with our own queer kind. We need spaces in which we can celebrate our cultural importance. Without space, we can’t be a community. Without community, we are lost.

WJC: Where is the space or location you feel most authentic?

JW: I take myself with me wherever I go. Apart from being alone at home, I always have to check how I react to those around me. It’s in my nature. It’s a constant process of trying to be my authentic self. I find it easier nowadays to be my true self with just one or two good friends.

WJC: While we see challenges, we also see progress. But how progressive would you say the LGBTQIA+ movement has been?

JW: The LGBTQIA+ movement? I think the community is being set against each other by right-wing groups and a right-wing media at the moment and we need not rise to their provocations and should remain supportive of everyone under the LGBTQIA+ umbrella. Sexuality and gender identity are intertwined and we need to stick together and lift each other up.

WJC: What does gay liberation mean to you?

JW: It means not forgetting how far we have come and knowing that the fight is not over. It’s about those on the front line. It’s the courage of non-binary and transgender people, gay men, lesbians and all within our acronym being out and living our lives how we choose. That encourages others to do the same.

MARIA BATHER

FOUNDER, FRIENDLY SOCIETY, SOHO, LONDON

WJC: Who is Maria Bather?

Maria Bather: I’m Maria Bather and I am what I am – and need no excuses.

WJC: What is the Friendly Society and how did it become part of your life?

MB: The Friendly Society is a wonderful Soho institution full of wonderful avant-garde people who make every day a pleasure in the workplace.

WJC: While we see challenges, we also see progress. How progressive would you say the LGBTQIA+ movement has been?

MB: I believe that we are in the best place that we have been in history, though as with all minority communities, one must always be aware to constantly look over one’s shoulder. Currently one cannot ascertain what may be around the corner politically, so we must remain on our guard and ensure that we don’t take our rights and the supporting laws for granted. We must always move forward and push for an even more inclusive and tolerant world – for everybody, regardless of where they sit geographically. We’re in a great place, though one must keep moving forward.

WJC: Where do you feel most authentic?

MB: A wild night in the West End surrounded by my beautiful friends and acquaintances. These are the times and places where I get to smile, laugh and live with people who celebrate the beauty of life and all it has to offer. It’s here where we can talk over our worries and ensure that everybody is in a place where they hopefully feel happy and real.

WJC: We talk of authenticity, but what does the term mean to you?

MB: Always be true to yourself – it’s the most vital and important part of who we all are as people. Authenticity is key to our progress together. So being true to that authenticity is something I love and encourage in everybody, no matter how difficult I know it can often be.

WJC: What advice would you give to younger people who are struggling to find their way?

MB: Life is akin to travelling up a downward escalator – “If you do not move forward as quickly as possible you will of course quickly descend to the bottom.”

WJC: They say that life is a great teacher, so what has been the greatest lesson you’ve learnt?

MB: Always treat others as you would be treated yourself. Remember when you call a call centre and are left hanging on the line for 20 minutes, it is not the operator’s problem, it is probably yours – you could have gone online!

WJC: What does gay liberation mean to you?

MB: Things like the Stonewall Riots of 1969 and how the community has moved on since those dreadful days of hurt and oppression. The Friendly Society is a perfect example of where all communities are in harmony together and having a wonderful time – while also ensuring nobody is left behind. And long may it continue – and I feel sure that it will, long after we’re all gone.

ANDREW LUMSDEN

GAY LIBERATION FRONT ACTIVIST AND CO-FOUNDER OF GAY NEWS

WJC: Who is Andrew Lumsden?

Andrew Lumsden: I’m a ground-dwelling ape with restricted sight, hearing and perhaps intelligence compared with other species on our planet.

WJC: What is the Gay Liberation Front and how did it become part of your life?

AL: It began in New York in summer 1969. Two young white students, Bob Mellors and Aubrey Walter, got themselves to America to find out what it was all about, attended a Black Panther Revolutionary People’s Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in September 1969, and were back in London spreading the news of Gay Liberation by October. I heard of it in November 1970 and rushed to be part of it.

WJC: In what ways do you think the Gay Liberation Front has had an impact on your life?

AL: It calls itself a “revolutionary” front and it revolutionised my life. No other politics had really seemed significant to me before. I was a soft leftie and a 29-year-old journalist at The Times newspaper before.

WJC: Can you imagine a world without the influence of the Gay Liberation Front?

AL: I can imagine such a world for I lived in such a world. I was born in 1941, when male homosexuals were in Nazi concentration camps, marked out for special scorn with pink triangles sewn on their prison uniforms. Lesbians were in the camps wearing the black triangle patches of troublemakers – a most honourable sign! – and trans people were given black or pink according to how the guards chose to understand them. I can remember such a world.

WJC: What advice would you give to younger people who are struggling to find their way?

AL: I’m shy of giving advice because ten years of a British government by the oldest authoritarian party in Europe – the Conservatives – has left young people grossly impoverished compared to how it was for young people in the 1960s. All I’ll say is, when everything’s against you, remember the illness – homophobia – is theirs, and that you are the sane and healthy one.

WJC: Do you feel a new sense of hope and change in the hearts and minds of the younger queer people you meet and work with?

AL: Yes! An evolution, something new, a transformation – something wonderful.

WJC: How do you feel about the term “queer”?

AL: When I first heard it five or six years ago, it was actually a shock, but I’ve come to see it as a friend.

WJC: So do you understand why some people are against using it to describe themselves or others?

AL: Yes, for older people, because if you’ve been verbally abused with the word during your life, in prison, confronted by police, confronted by queer-bashers, it arouses terror within you.

WJC: When do you feel most authentic?

AL: I feel most myself when I’m anywhere with my partner.

WJC: What does gay liberation mean to you?

AL: Gay liberation in the West will be the day when men who are friends or family walk in the streets holding hands and people are pleased to see it.

This feature is taken from our Taking Back Control issue. Order your copy here.