Alba Zari: the photographer seeking her truth

Karl Lagerfeld once said: “What I like about photographs is that they capture a moment that’s gone forever, impossible to reproduce.” But what happens when, after 25 years, you discover that all those past moments you held on to are simply capturing a lie?

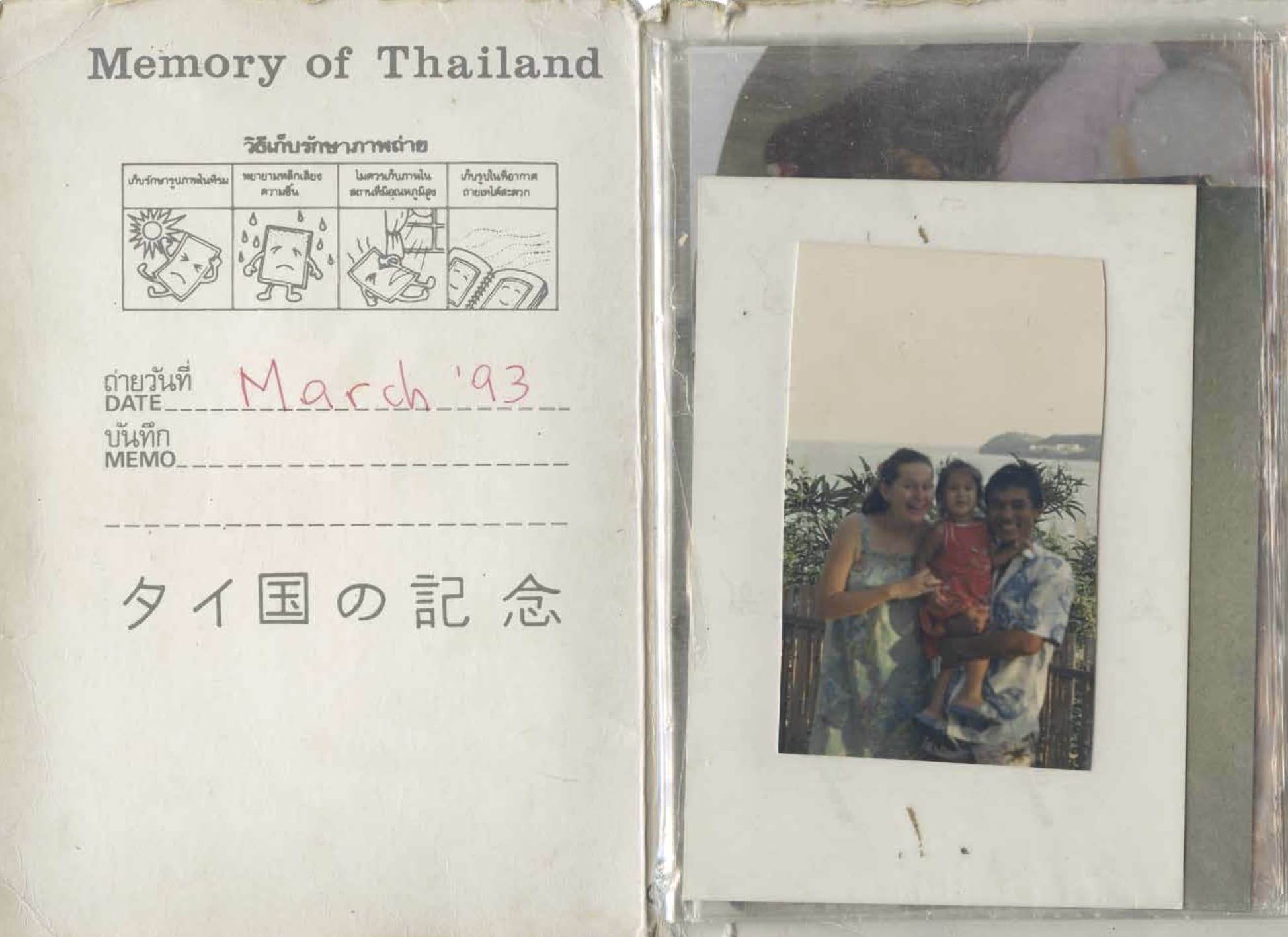

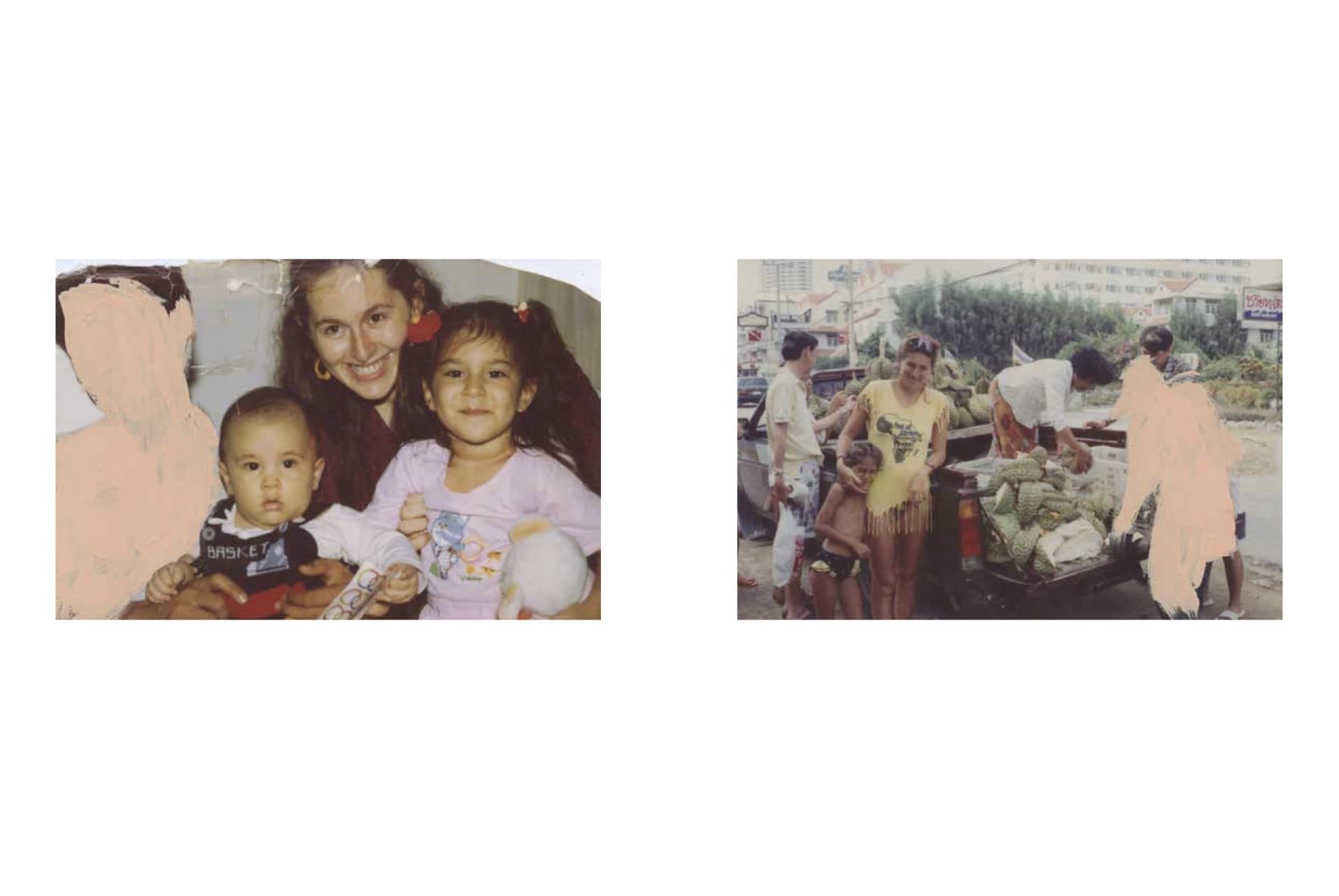

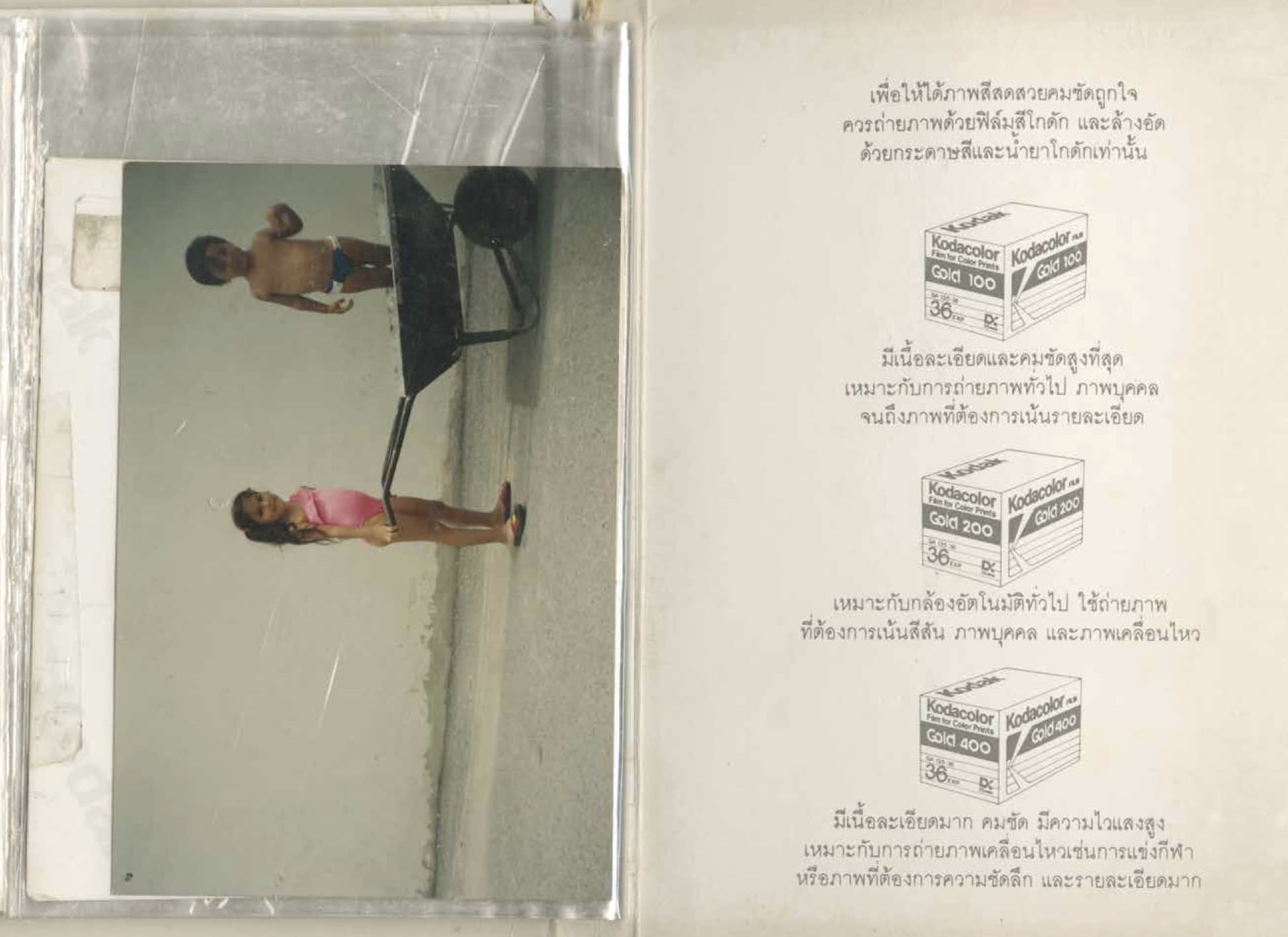

This is the story of Alba Zari. Born in Bangkok in 1987, she moved to Italy when she was only 8 years old and, 17 years later, she lost herself when she discovered the truth about her father. This is The Y, a never-ending scientific and photographic investigation with only one aim: the search for an absent father, someone capable to give Alba her identity back.

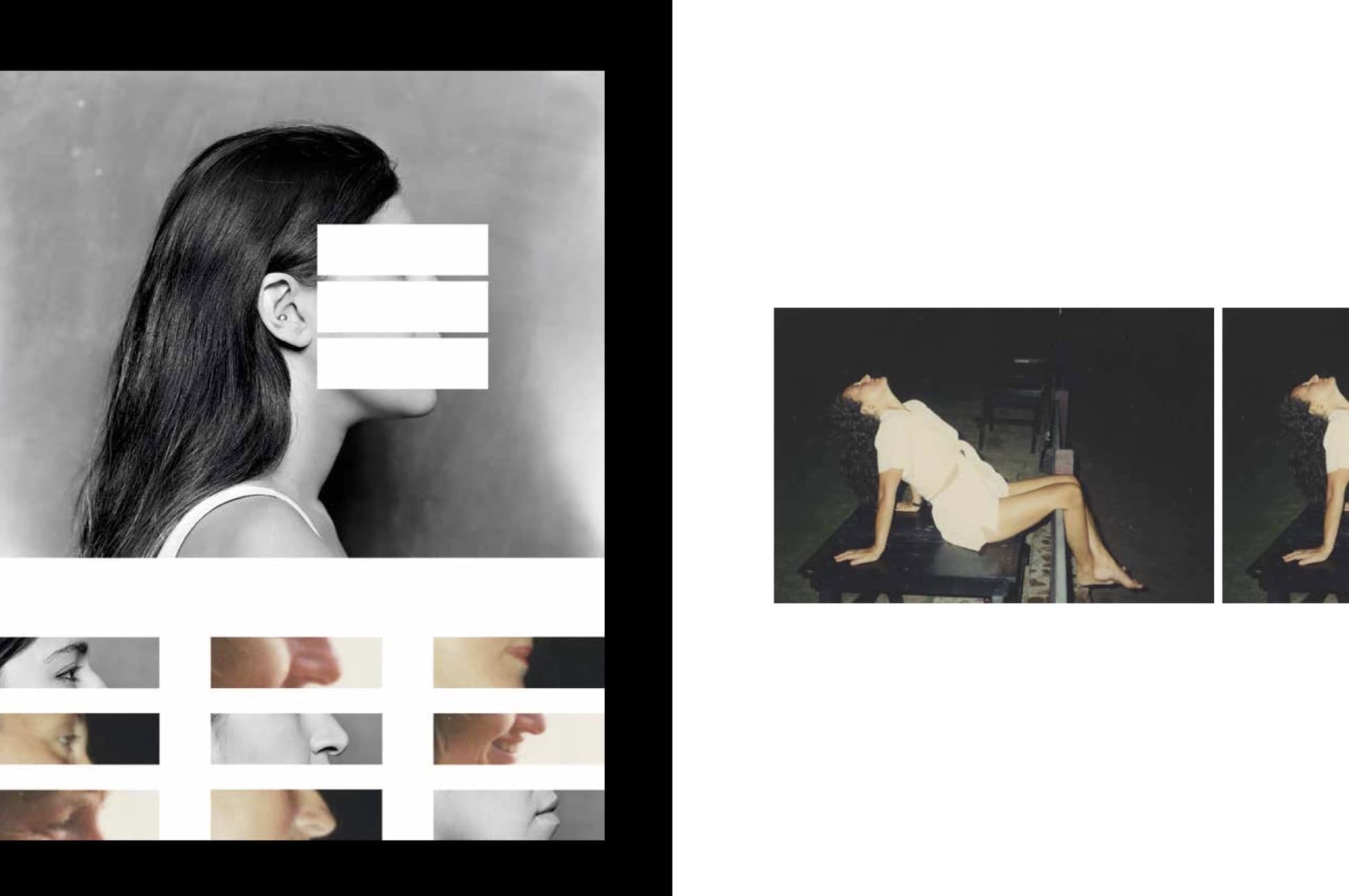

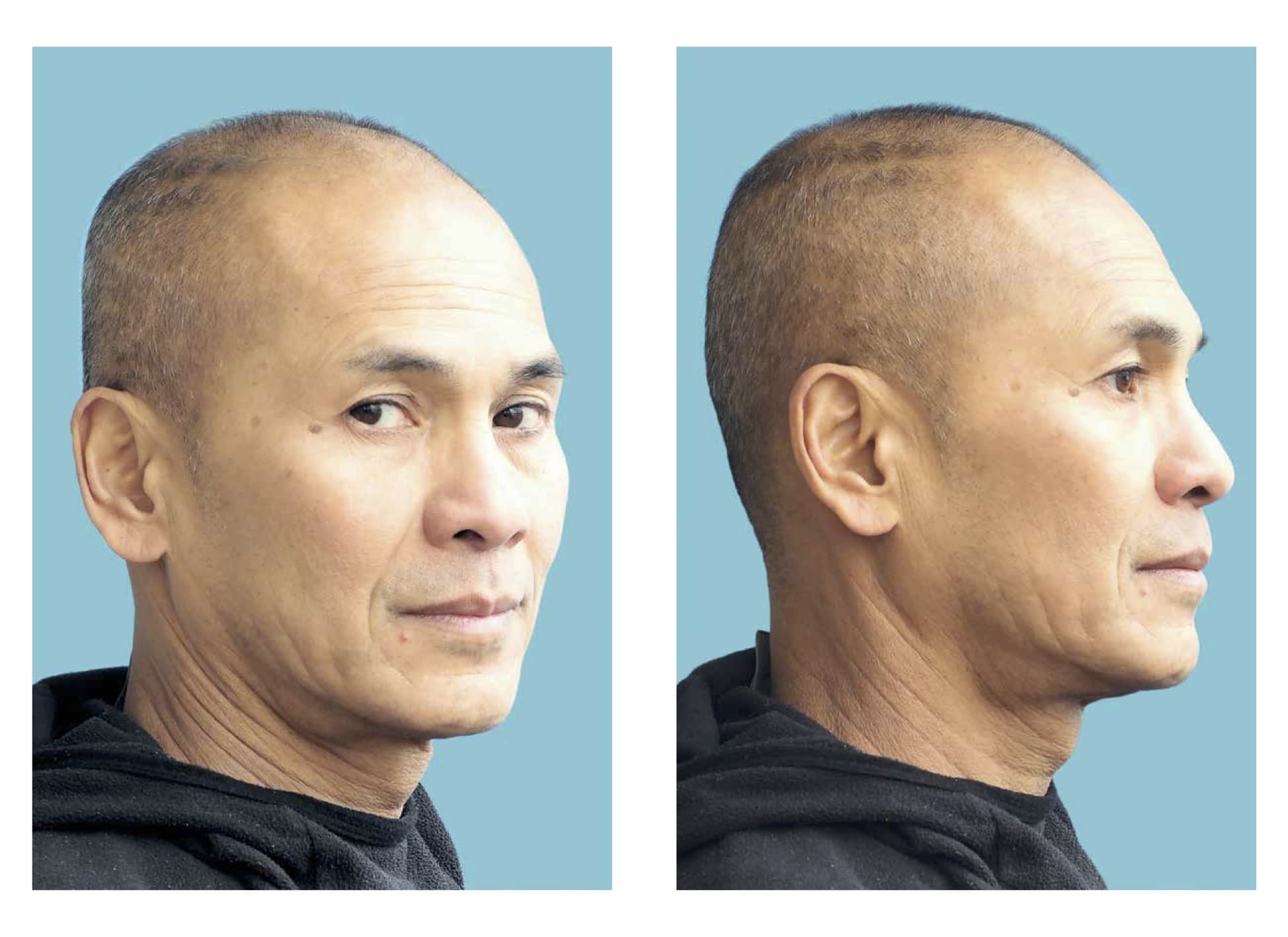

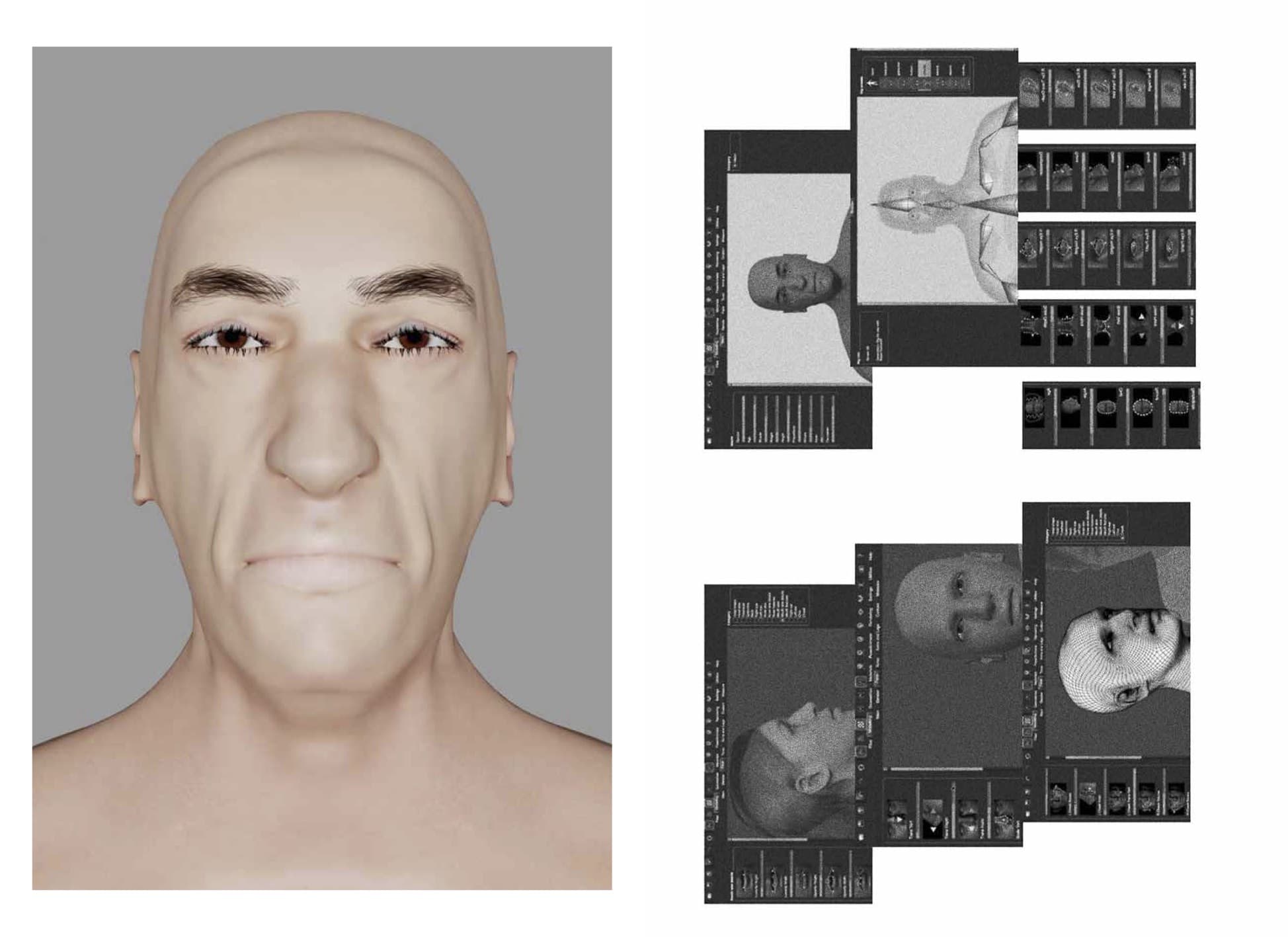

From DNA tests to photos and 3D facial reconstructions, Alba explores 25 years of unknown and documents her journey in the hope of finally find an answer to her questions.

Tell me about your story, how did you get into photography?

I studied cinema at the DAMS in Bologna and the first exam I ever did was with Claudio Marra on the history of photography. I immediately realised I was really passionate about visuals. My thesis was on the history of photography by sufferers of mental health and, in particular, following the Basaglia Law *, I did a mix of a history and a creative thesis as I went and shoot some pictures in the centres. I then moved to New York and went to ICP (International Center of Photography) for a year, I did my masters and had a more documentarist approach – which were my first works. I continued my studies at NABA in Milan where I learnt to have a more conceptual approach and a bit more materialistic, a bit freer, because fashion is a bit more documentarist, it follows schemes. So, this is part of my story, I started from cinema but we’ll see. I would like to go back to work in cinema now.

In particular, talking about your project, The Y, and when you discovered the news about your dad. The constant search of this mysterious man in a period of your life when you were already an adult, how did it change you?

First and foremost, my identity changed. I found it out when I was 25 years old, so I was already formed as a person. I had already accepted a series of things, such as my dad’s missing presence – which is something I already elaborated on. The thing that stuck with me and the one I started working on is my identity. This changed because I thought I was born and bred in Thailand with a father, still absent, but who was still Thai and was still my brother’s father. I then found out I had this hole, this missing information which is half of who I am as a person. I had the necessity to find out who I actually was. This search for the truth, proof – the project is entirely based on facts because documents were the only thing that was going to tell me the truth. So, I structured it this way for a personal need to discover the truth.

How did the project affect the relationship with the other members of your family?

For the better, for sure. It’s a path of acceptance because I understood why this information was missing my whole life – so I understood where they were coming from and, on the other hand, I had this need to elaborate this information and to find out the truth. We got closer because I understood the reason behind their actions, and I managed to do this without asking them anything but doing it all by myself.

Something really interesting is that you used a scientific method despite the fact that this project is very personal to you. How did you manage it?

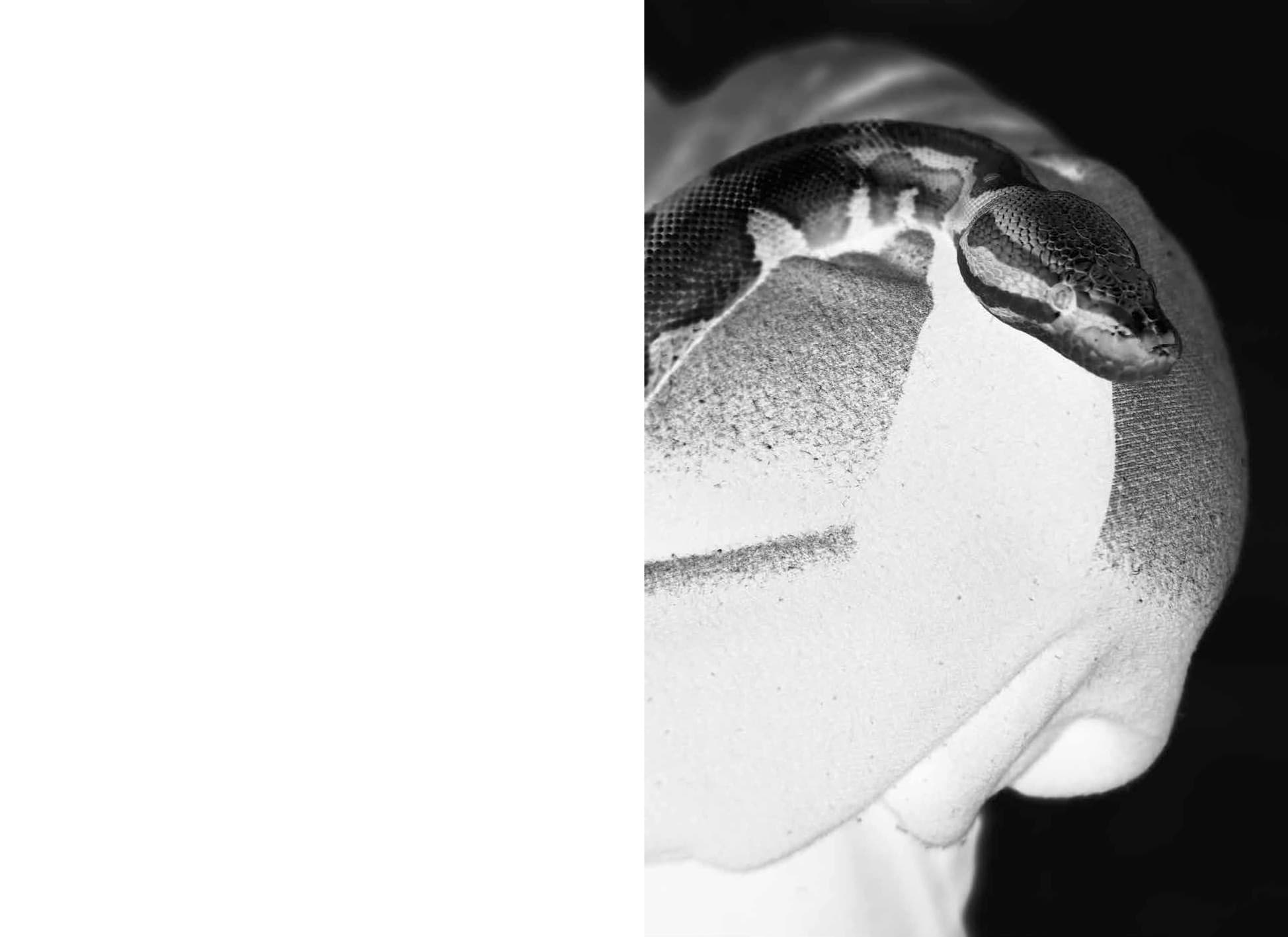

Because it was work. I used a scientific method to keep an emotional distance. I said, “okay these are the documents”, I tried to archive everything. And I thought of this as work, almost like a detective. By working this way, I managed to keep this distance – that obviously wasn’t always there. In my book that just came out with Witty Kiwi, there’s a part of the project that wasn’t shown: it’s the part in negatives. These are the images that have been left in negatives due to that lack of information and development. It’s the most evocative and emotive part of this journey where I often received bad news because I never found my father. I put him together with an image, with an avatar and physiognomy, so yes, it did help me keeping this distance. Although this was the aftermath of a lot of emotions, of the need of information. I wanted this to be an important work, not just for me but for other people as well, something that went past pain, past not having a father. There are a lot of families with a father that exists but that is absent, and maybe that hurts too. It’s the absence of a loved person that can unite people.

How do you feel now that this project is over?

The project isn’t over, I did everything I could to find him, so it’s a bit like I am at peace with it. But it’s still an ongoing project because, maybe, it can’t be over until I find my father. It’s something I will always carry with me. Life is strange – I often ask myself if I will ever meet him, if he’ll ever get in touch, because it’s someone that exists. It’s life, right? So, I don’t think I will ever be able to finish the project until I get an answer in my personal life.

Do you feel better now compared to when you started it?

Yes, absolutely. The more you face it, the more you see it, the more you elaborate it, the more you can let it go and be at peace with the past.

Absolutely. Talking about photography in general. As this project was so personal, what usually inspires you on a daily basis?

People’s stories. I don’t think about photography as a “I have a camera; I will shoot some pictures because…”. Sometimes I see someone that looks interesting and think “I’d like to take some pictures of them” but I don’t bring my camera with me. I think photography is like a story, a concept, so if I find an interesting story I write and research before shooting it.

By documenting stories, what is it that you hope to communicate to people?

A feeling of closeness to the story. To elaborate some things, we feel inside and that maybe we are not used to think about. It can be family; it can be identity. To reflect about who we are, our identity, our concept of family, through a story that isn’t our own. I think these are things that affect everyone, especially nowadays.

What do you have planned for the future?

My next photography project; it’s called Occult. I did a little exhibition at the Museo D’Arte di Ravenna for a photography exhibition called Looking On with other young, emerging Italian photographers, and it’s something I just started. I started researching archived material and the project will be on the propaganda of this cult, which is called Children of God and are a hippie cult that started in 1968 in California. They go around the world and believe in free love, that the body of the sacrificial woman belongs to God. I’ll do the research in London and I’ll shoot the images in Berlin, India and Thailand – which is linked to my personal story anyway. In a way, they are connected to my mother’s family so I will go to these places where my family was and take photos of these cults.

* Basaglia Law is the Italian Mental Health Act of 1978 which signified a large reform of the psychiatric system in Italy, contained directives for the closing down of all psychiatric hospitals and led to their gradual replacement with a whole range of community-based services, including settings for acute in-patient care.