Artist Romily Alice Walden talks post-internet culture and neon nudes

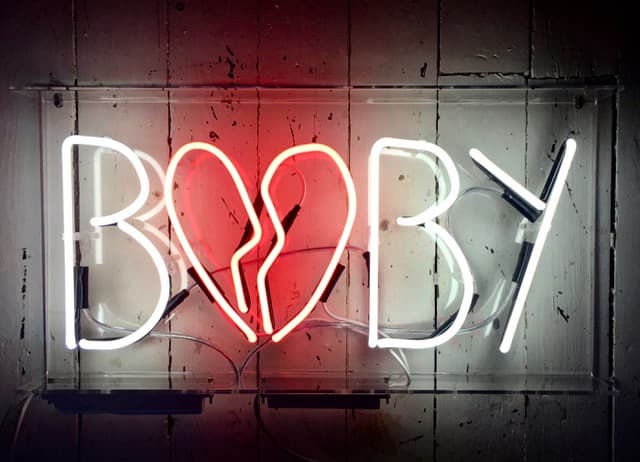

Romily Alice Walden’s work is the exemplification of how the form can be used to create art that is powerful and Instagram-able in equal measure. Concerned with gender and “its interplay with other social categorisations and power differentials”, Walden’s most iconic creation is Utopias (IRL//URL) where she took neon off the walls and onto sculptural stands. As she explained her work, “questions modern society’s relationship with looking, being looked at, gendered hierarchies, pleasure and the body”, and Utopias is the embodiment of this. In the world of post-internet culture, Romily Alice Walden seeks to work hard in the digital age of instant gratification, and so we caught up with her to find out how it’s working out…

How did you start creating your neon art?

Whilst I was at art school I did a one day course in neon bending at Neon Workshops in Wakefield. I immediately loved the process, its very hands on and very precise. You’re bending tubes of glass in custom-made fires and then bombarding your finished shapes with noble gases. There’s a lot to learn and its not an easy process but when I realised that I wanted to work with neon I didn’t want to go down the route of having someone else fabricate my work for me so I found a mentor and went to Berlin to study glass bending with him. For the past few years I’ve been focused on getting my bending skills up to scratch and now I’m getting to the point where I can step back from neon and start to expand my practice again to include other elements and push the possibilities of how the material can be used. With the work at AAF ‘Utopias (IRL//URL)’ that expansion has meant taking the neon off the wall to create these free standing sculptures and adding a coded element to the work to allow the neon to interact with the environment.

You’re interested in presenting “the value of labour in an age of instant gratification”, how do you feel art has been affected by these changing times?

Our digital lives mean that everything feels instantly accessible; most artists and galleries have social media accounts that allow you to feel like you’ve seen a piece of work without having been physically in front of it. I think there’s a lot of good that comes from that in terms of the democratisation of contemporary art – galleries and white cube spaces can be very intimidating so if Instagram etc. help people to connect with art I think that’s a positive. At the same time as an artist I think it can feel quite alien to devote so much time, energy and money into acquiring a traditional skill, when the cultural norm is to pay someone else to make it for you and in that way instantly get what you want. For me the physical labour that goes into a piece of work is an essential part of the process so it feels important to take the time to do that myself wherever possible.

Do you think social media can promote real life change?

Yes. I think we’re past the point where we can create a clear division between our online and offline experiences, the one has blurred into another. I think there was a time where as a culture we tried to hold onto these compartmentalised ideas of ‘real’ and ‘virtual’ or online and offline, but I think that time has passed. The impact of what is said and done online is felt in a very real way offline – you can see that in an extreme way in examples of online shaming or trolling – Jon Ronson wrote a very interesting book about public shaming and the internet which is definitely worth reading. I think in a positive sense social media has the capacity to mobilise people. Protests can be organised instantly and messages can be spread more widely and quicker than ever could have been imagined pre-internet.

What would you say defines post-internet culture?

“The postdigital asserts that computational technology is now (or once again) ‘post-screenic’ (Bosma 2014), that it has broken out of the confines that divided it, as new media, from other media technologies, and has now come to saturate the everyday enviroment.”

Dieter, M., Berry, D. and Cramer, F. ed., (2015). In: What is ‘Post-digital’?. United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan.

I think the quote above is useful in terms of understanding this idea of internet culture moving beyond an optional technological tool and becoming a function of our day to day existence. The academic Nina Lykke talks about the use of the word Post as meaning both something that moves past the referential (in this case the internet) and is still tied into and living amongst it. Post-Internet to me describes this strange time where we as a culture are trying to adjust to a radically altered way of living where one of the primary modes with which we communicate as a species has altered beyond recognition.

Why do you think neon is so big right now? What about the form appeals most to you?

Neon feels like an old-school television, it has the same capacity to draw the eye. We want to look at a neon in the same way we gravitate toward a screen. I love the alchemical quality of it, the hot making, the injecting of gases and mercury, the electricity arcing between the two electrodes. I think there’s an electro-chemical quality to it that looks a lot like magic in a way that LEDs and other lights can’t recreate.

Do you find creating portraits of the female form affects how you perceive beauty?

I’ve always found our cultural standard of beauty to be insufficient; my own feelings about what is beautiful are a lot wider than those perpetuated by our mass media and I think that’s part of the reason I’m so fascinated by the body and keep coming back to it within my work. I don’t want everyone to look the same, I think what makes the body so interesting is its inherent individuality and I think there’s always going to be a beauty in that.

What can we expect from your work at the Affordable Art Fair?

The work at AAF is my latest installation ‘Utopias (IRL//URL)’. It’s a body of work I developed whilst researching female sexual agency in connection with digital culture. I’m interested in the way that the female body functions as a sight for the perpetuation and contestation of fantasy. The installation mixes neon with concrete and living plant-life; I wanted to create a visible collision between the digital and the natural.

How did you come to work with AAF?

I was approached by Cassie Beadle of Cob Gallery who is curating the ‘Recent Graduates’ exhibition at the fair and I was obviously very excited to take part.

Who are your must follows on Instagram?

@unityskateboarding, @arttechspace, @hebe_konditori and @plantsonpink

What’s next for you?

I have a couple of exhibitions lined up for next year that I’m pretty excited about so I’m going to be holed up in the studio for a few months creating a new body of work for those.