Denim is fashion’s most inclusive fabric

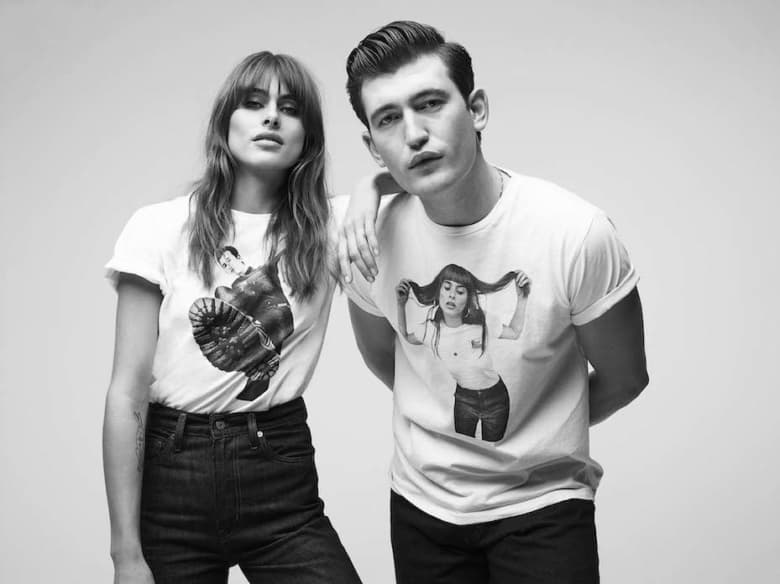

Whilst it’s gone through many incarnations, denim remains the one constant in our wardrobes. From the boyfriend jeans of the 90s to the drainpipes of the emo era, the fabric’s versatility has allowed it to ride the zeitgeist of every generation. Denim has stood the test of time, that’s for sure, but it’s also one of the few materials that transcends divisions of class and gender.

Fashion, as much as it’s about self-expression, can also be used to “read” your status according to classist norms or, through the divisions of “womenswear” and “menswear”, force you into subscribing to binary definitions of gender. Denim might have begun as workwear for miners and cowboys, but since then it’s become one of the few unisex styles we have, and even gone on to be spotted on movie stars, academics and even Prince William. When you embrace denim, then, you refute the idea that anyone should be able to slot you into a box at first glance according to your gender or perceived social class. Like people themselves, it transcends easy divisions and has its own, rich backstory.

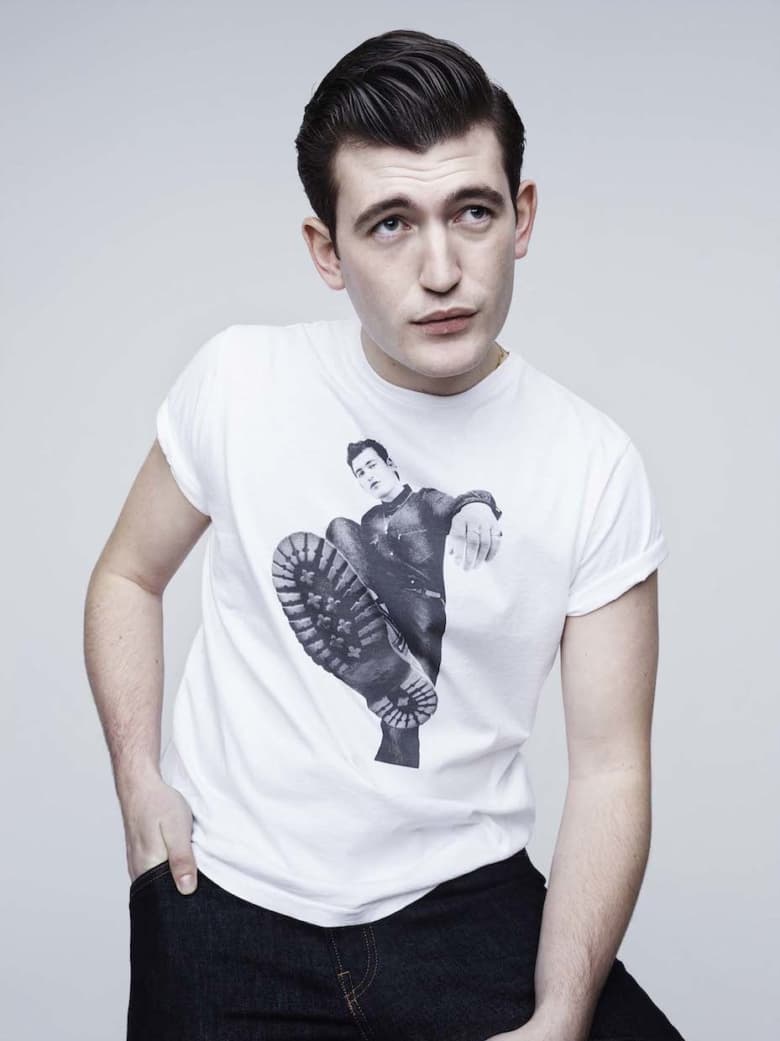

Nowadays, due to the universality that the fabric has attained, a good pair of jeans can take you pretty much anywhere. In the past, however, the fabric was intrinsic to specific subcultures. In ‘50s America, for example, blue jeans clothed dissident youth grouping together to escape society’s racism and classism. Within greaser culture (yes, this is what Grease makes reference to) adolescents of Mexican, Italian and Puerto Rican descent wore denim like an armour, embracing its proletariat connotations in order to celebrate their class identity despite the discrimination they faced elsewhere.

Whilst jeans became a symbol of youth rebellion in this era, further down the line it would become integral to different LGBT communities. Adopting normcore denim as a way of blending in with wider society, queer people of the ’70s would make themselves and their sexual preferences visible with the “hanky code”. In a time when they were still routinely harassed by the police, they would place a hanky in the left or right back pocket of their jeans as a subtle sign to other members of the community.

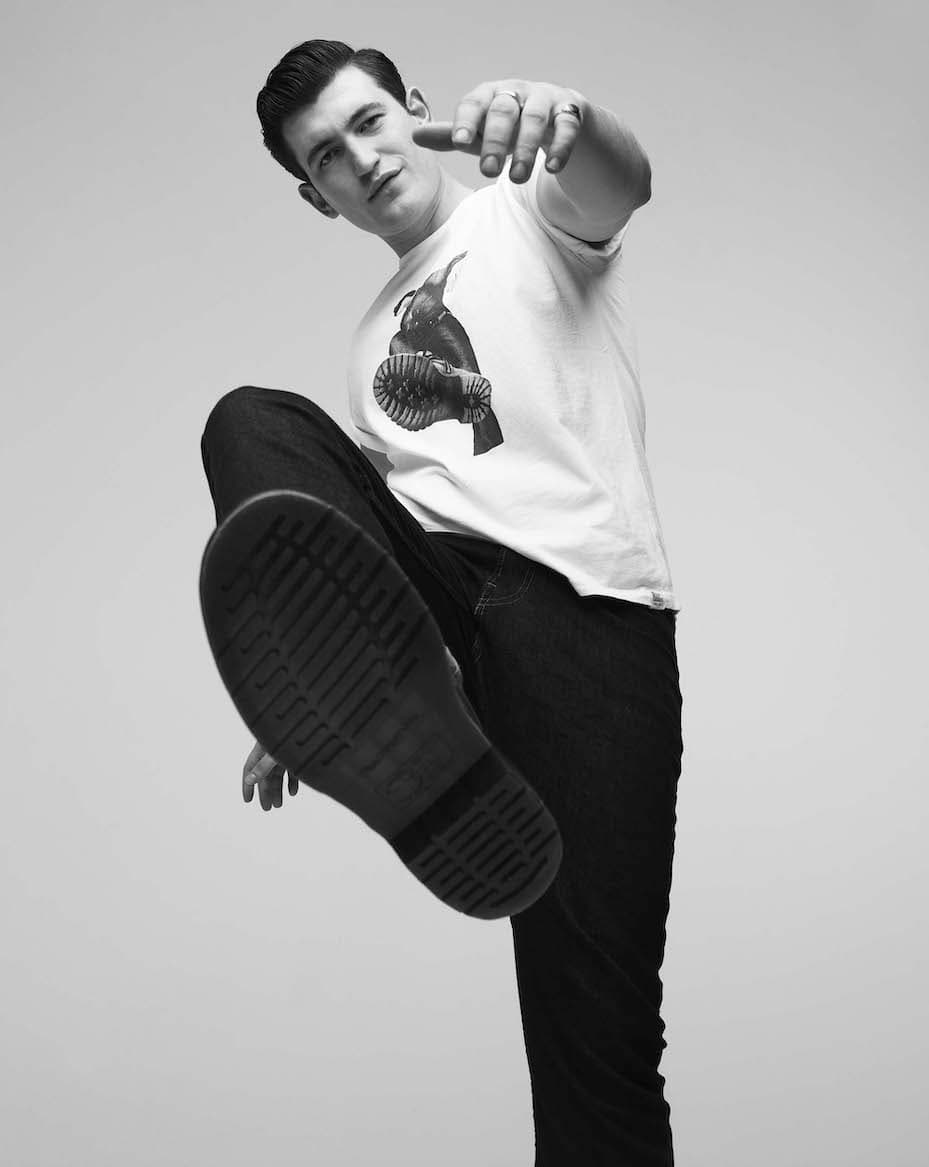

Denim’s mainstream appeal, which provided queer communities much-needed safety and camouflage, would later be subverted by the ‘90s grunge movement. In this cultural moment, young people spearheaded a backlash against the hyper-consumerism of the ’80s; embracing a prototypical normcore that rejected brands and trends. Thanks to this ethos, baggy jeans would become the go-to item for a sea of young people looking to stick it to the man and reject ‘more is more’ materialism.

When you wear a pair of jeans today, you carry the weight of all these stories – and more – on your skin. In the present, denim is one of the few truly unisex and unclassifiable fabrics. It’s this, when combined with the fabric’s rich history, that makes it into a canvas onto which we can project our hopes for a more egalitarian future.