Drag is so much more than high-glamour queens

What football is to cis-het men, Drag Race is to queer people: meaning that its influence is practically inescapable for anyone under the LGBTQIA+ umbrella. As a result of its runway success (see what we did there?) drag race viewing parties and language like “bye Felicia” or “kiki” have all become commonplace in queer spaces. Out with the community, cis-heterosexual people are among some of the show’s biggest fans — meaning that the series has gained the kind of universal relevance that would have previously been unthinkable .

It’s great to see an art form so closely tied to the LGBTQIA+ community gain this kind of cultural significance and it’s hard to think of a cultural figure who has done more for gay visibility than Ru Paul — except maybe Ellen Degeneres, back before she started hanging out with war criminals. With the show spanning 11 seasons plus an “all stars” spin-off, even spawning “Drag Con” events across the US, its bankability arguably paved the way for the Queer Eye reboot, which we should all be thankful for. However, the show’s mainstream success has come with an uncomfortable side effect: a subsection of queer performance is being taken as representative of the whole, flattening a rich cultural history.

Since its inception, Drag Race has placed its emphasis on drag queens and a seamless, high glamour aesthetic. Whilst no-one’s denying the validity of this form of drag, it obviously doesn’t feature the drag kings whose contribution to queer culture should not be undersold — particularly as one of the most important figures in the Stonewall riots, Stormé DeLarverie, was also a drag king. Additionally, the form of drag popularised via Ru Paul doesn’t reflect the many different performers associated with the queer avant-garde. The “terrorist drag” of artist Vaginal Davis — one of her personas includes white supremacist “Clarence” — would not necessarily find a home on Drag Race, even if she is widely acknowledged as one of the most important living figures in queer performance.

The launch of Drag Race UK back in October consolidated the original show’s global reach, whilst championing a particularly British variety of camp (Kim Woodburn, anyone?). Yet to anyone who has first-hand knowledge of the scene, it’s clear that the show doesn’t reflect the diversity of the UK’s drag performers. Whilst there are plenty of cis male drag queens, there are also performers like drag ogre SHREK 666 pushing the boundaries of personhood, initiatives like Kings of Colour platforming outstanding performers despite wider programming prejudice and non-binary queen and artist Victoria Sin‘s Jessica Rabbit stylings. As performer Chiyo Gomes, writing for the Independent, has argued; “the UK drag scene is punk because of its authentic diversity”.

Drag turns subversion into an art and opens space to explore overlooked experiences — of gender and sexuality, but also race and class. As a result, any attempts at a mainstream crossover were never going to be seamless. Speaking to drag king Georgeous Michael, they confirm that the perception of drag promoted by the media is a one-dimensional one. “If you look at the kind of drag that gets picked up in the mainstream, it’s very focused on queens and, within that, on glamour drag which can uphold some pretty fixed (sometimes offensive) ideas about gender and femininity. Because that’s all they see, a lot of people assume this is drag, but in fact it’s just one part of a very diverse art form.”

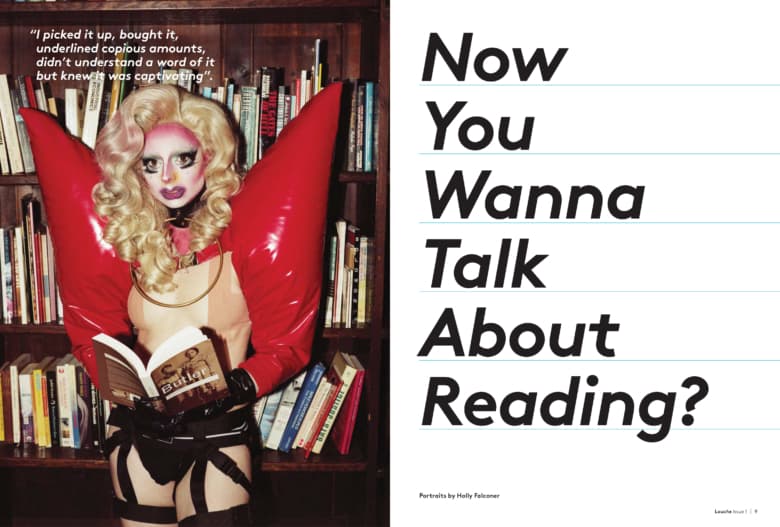

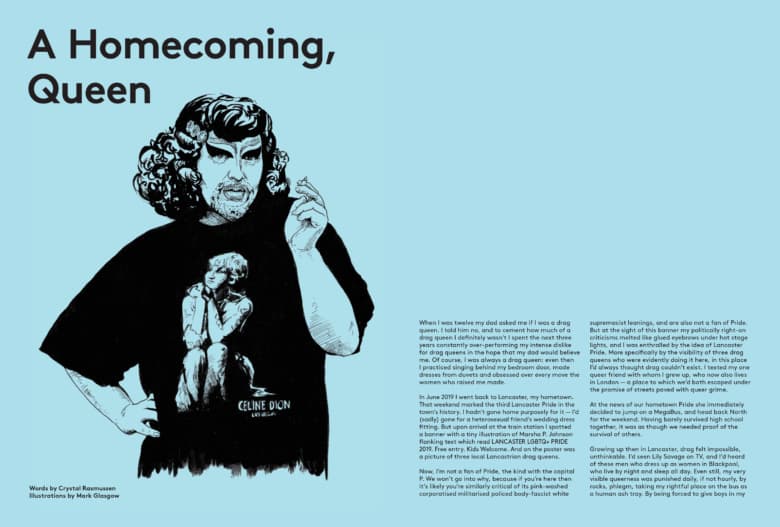

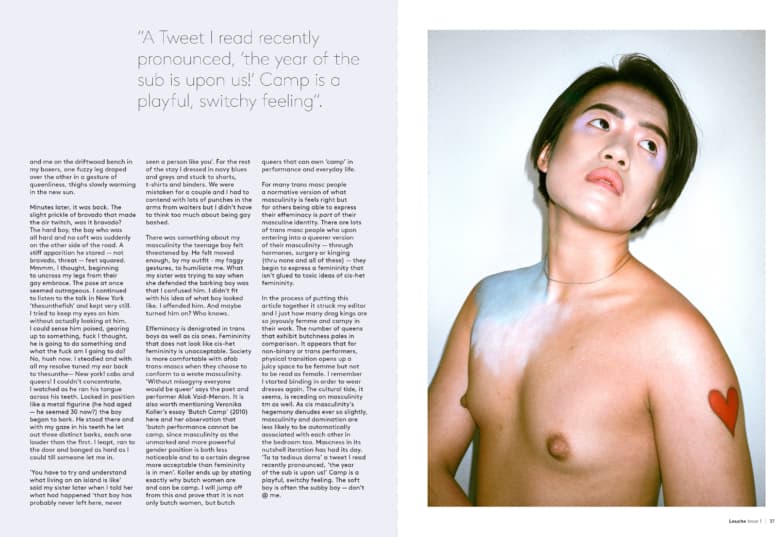

As Georgeous sees it: “The drag king scene in the UK, and London in particular, is really thriving, but you wouldn’t necessarily know it from what gets shown on TV or covered in the mainstream press.” So, in order to more accurately represent their drag community, Georgeous fathered Louche — an independent print magazine on the topic of drag and queer performance, with a focus on some of the UK’s most essential performers. “Louche aims to celebrate drag today, with an emphasis on the audacious and the radical,” Georgeous says, succinctly explaining the project’s guiding principle. A casual flick through the magazine suggests that it has been successful in its ambitions — it’s a veritable treasure trove of content. From meditations on masculine tenderness to an essay on classism in drag from author, queen and “full time Celine Dior fan” Crystal Rasmussen, Louche issue 1 is filling the gaps in the way drag is represented.

Yet the project isn’t just about documentation — it’s also about giving important ideas about drag and the UK’s performance community room to breathe. As Georgeous puts it: “The magazine is also here to interrogate. There are a lot of important conversations happening right now within the performance community — about representation, for example — and it’s great to be able to provide a platform for these discussions.” The magazine’s manifesto puts a particular emphasis on performers that trouble the binary between “king” and “queen” within their practice, a conversation that Georgeous is keen to see explored both on and off the page. “It’s great to see performers who not only test but explode these boundaries: those who problematise gender within their acts for example,” they say. “This might be through drawing attention to the absurdity of shaving like John Smith or playing with different gendered positions onstage through having both ‘king’ and ‘queen’ personas, like HarleyD.” Yet it’s not just about breaking down the gender binary in drag. “There are people using drag to think way beyond gender, into territory beyond what it even means to be human: this includes artists like Oozing Gloop, a green ‘drag thing’ interviewed in Louche mag Issue One.”

Overall, Georgeous hopes that they can create an archive that will reflect the vibrancy and diversity of the UK scene, allowing it to be preserved for future generations. “We hope the magazine also functions as a living archive, especially when so much of live performance is ephemeral, fleeting and momentary, and thus vulnerable to being lost from history.” By making its mark in this way, Louche should hopefully serve as testimony to the fact that the queer underground is alive and well — even if much of it doesn’t cross into mainstream media.

As part of Fringe! Queer Film and Arts Fest, Louche will be running a late-night, drag-along screening of The Little Mermaid at Rio Cinema on 15 November.

Check out some spreads from Louche’s first issue below.