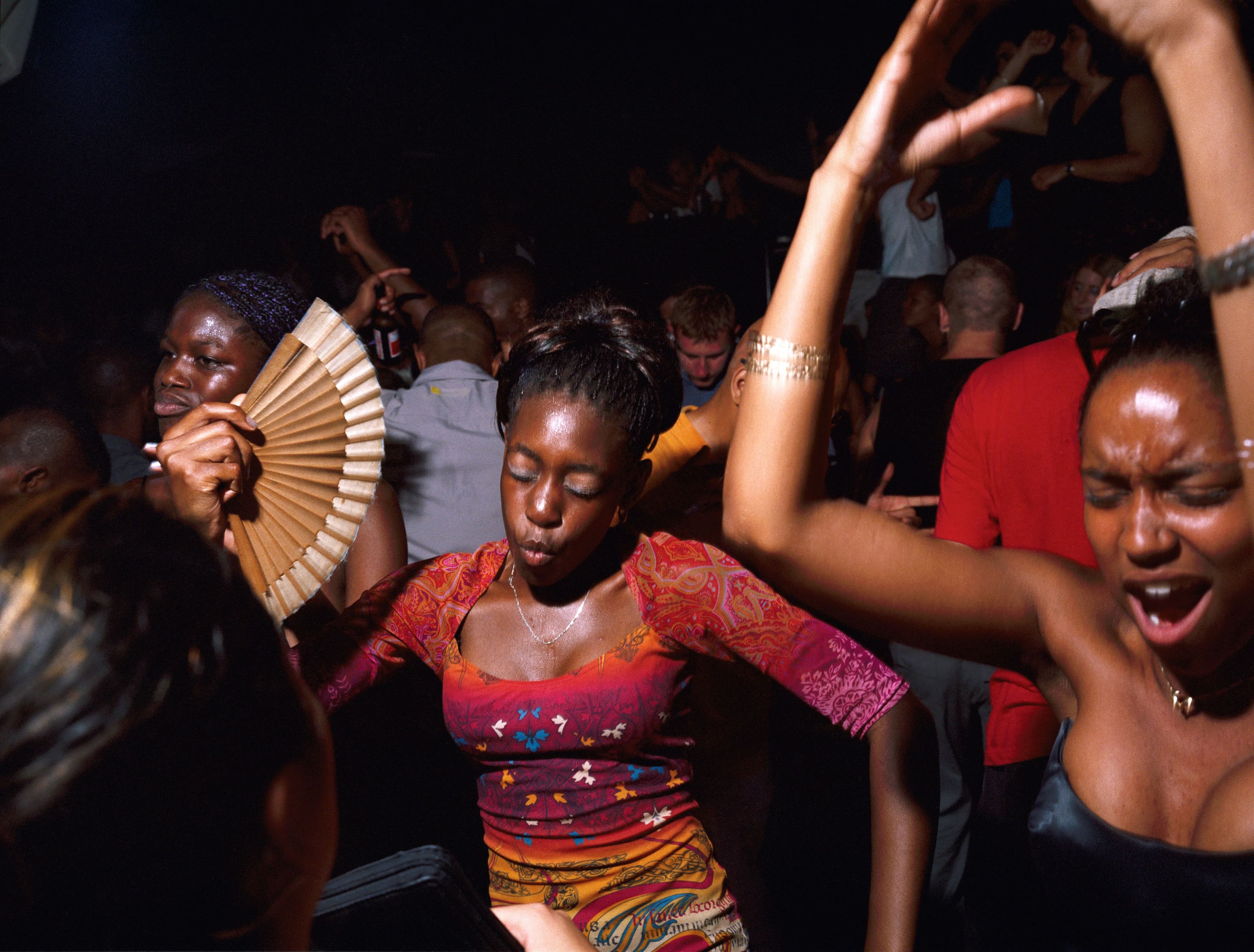

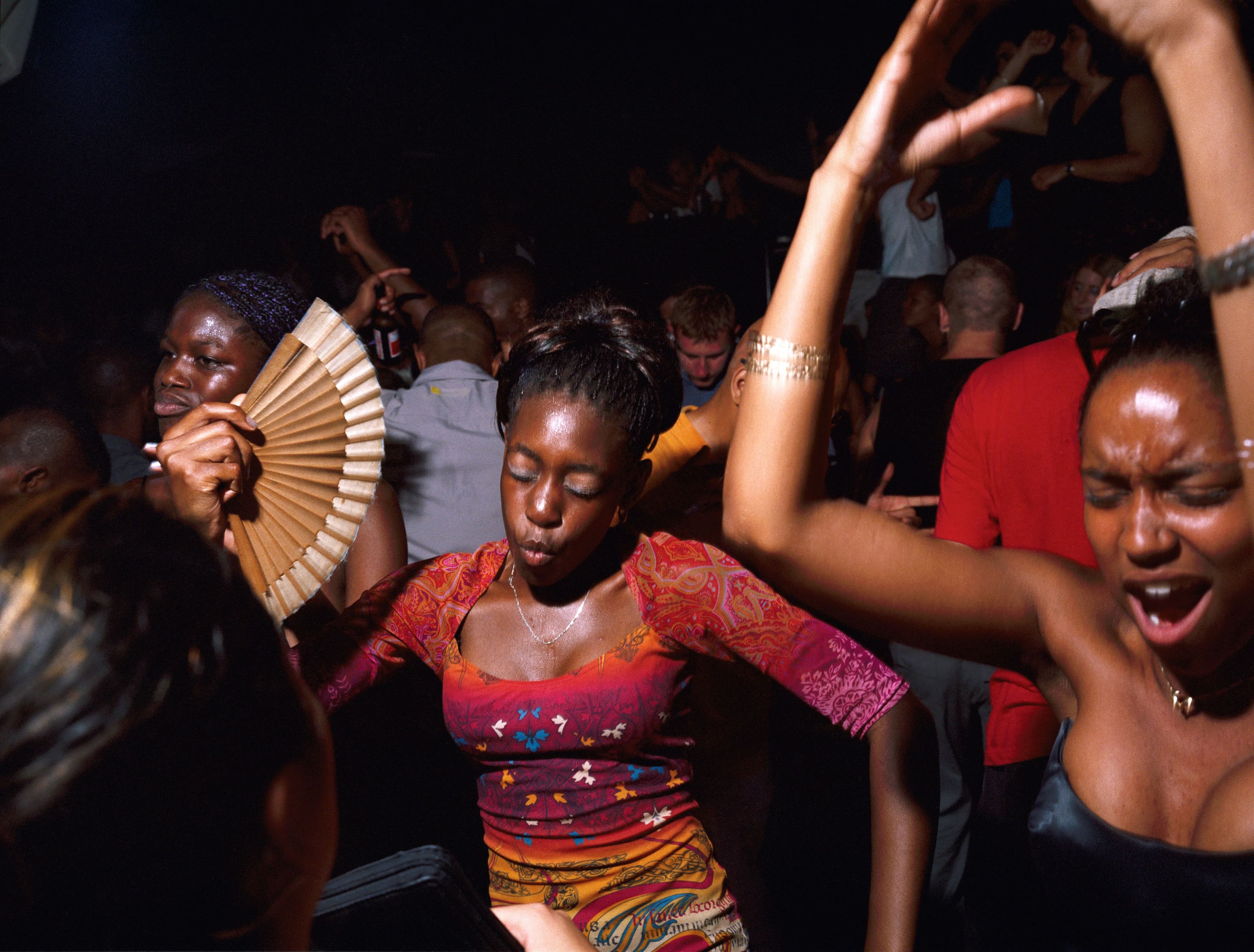

Ewen Spencer, the eponymous photographer of the UK Garage scene

Newcastle native, Ewen Spencer, has seen and photographed it all. Famous for his photographs of the beginnings of the UK garage (UKG) scene and its subsequent transition into grime, Spencer has been at the epicentre of youth subcultures for over the last 20 years.

From first picking up a camera in 1992 aged 21 at his art foundation course at Newcastle College to studying Editorial Photography at University of Brighton only a year later, it was obvious that Spencer had an instant affinity with the instrument – and to capture people.

Spencer started out photographing UKG and other nightlife scenes for Sleazenation, the 90s club publication, and quickly went on to have his photos featured in The Face and i-D magazine in the early noughties. Alongside covering numerous raves across the country, Spencer photographed a list of all-star music heads, from underground grime and garage artists to The White Stripes and more recently slowthai.

The UKG sound started to emerge on dancefloors in the early 1990s, DJs such as Tuff Jam began to play faster tempo remixes of vocal tracks from the US and Italy, it was perfect for the club scene and its popularity grew as quickly as the music spread across venues in London. By the late 1990s, UKG had developed its own influences and style, distancing itself away from the original US ones.

Queues of people in Versace and Moschino suits trickled down London’s streets on a Friday night. Along with the music a new style had emerged from Garage, people dressed up for the events and it was all about the brands –they would even keep the tags on the clothes to make them look brand-new. No-one could get enough of Garage, the scene quickly exploded from underground to mainstream. Jay Z, David and Victoria Beckham even showed face at one of Steve Gordon‘s notorious Twice as Nice parties at the Colosseum in Vauxhall.

Not one to shy away from a good time either, Spencer spent his teenage years and twenties at numerous garage parties and raves throughout Europe: Ibiza’s Café del Mar, Goldie’s drum’n’bass event Metalheadz and of course Twice as Nice.

Probably the most notable reason for Spencer’s connection to underground music scenes was his own relationship with the subject, music was a big part of his life growing up, specifically the record covers of his favourite LPs. Spencer was introduced to Northern Soul music while he was a mod, it ignited a love affair with the genre still holding strong over 25 years later.

Scroll down to read the full interview:

When did you first pick up a camera and what drew you to photography?

Okay, the first time I picked up a camera was at my art foundation course at Newcastle College in 1992, I was about 21.

What happened from there to you studying photography at Brighton University?

I was 22 (when I went to University), I went to the college course in Newcastle – the simple process was that you’d then apply at universities and I got into Brighton, which took me by surprise. Within a year from starting that art foundation course I was in Brighton studying for a degree in photography.

Did you have one of those wow moments when you picked up the camera, like ‘this is what I want to do’?

Yeah, I had spent a lot of time in Newcastle city centre where I was working when I tried photography. It was part of the foundation course, along with lots of other disciplines like graphics and 3D, I tried photography and that was the one that bit. I took the camera that was loaned to us and two or three rolls of film, and I went and photographed people I knew in the city centre to characters, like the people in the shops where I worked. I liked the results and my tutor at the time thought they were really good – I pursued it, I just loved it and I got really involved in it and everything about it, reading about it, the technical side of it I obviously did that really quickly, I got to terms with that very quickly.

Did you have any photographers that shaped or influenced you? Or was it you creating your own style because you didn’t grow up around it?

I think we all grow up with it, I think its constantly there, photography. You’re aware of it or unaware of it. You’re unaware of how it’s influencing you unless you’re proactively thinking about how you want to use it in your life. I was looking at magazines like The face and i-D, just because I was interested in music and style. It’s not because I wanted to be a photographer, I didn’t even think about that, I never even contemplated the idea that I might be that person and then you know eight or nine years later I was, I didn’t imagine that could ever happen. When I started studying it the influences that most ran true for me were artists like Chris Killip, Tom Wood and American photographers like William Klein and Larry Fink, I looked at those people all the time.

Going from there, how old were you when you became aware of the rave revolution, did you attend any of them before you started working at them as a professional photographer?

Yeah, you know that picture by Dave (Swindells) which is part of the exhibition in Ibiza, I was living in the apartment above those guys where they were being photographed on the beach in Cafe del Mar. I was staying above the Cafe del Mar in the summer of ’89, I would’ve been 17. I looked a bit like that kid in the photograph reading The Sun newspaper, with the headline about the evil island. I was part of that movement, but from the North East, so probably wasn’t as progressive as some of the kids down south but we certainly made a go of it.

What drew you to actually start capturing the culture you were seeing around you and the nights that you were attending?

I just think I just photographed what I knew, Soul Music was what I photographed really, first and foremost The Northern Soul Scene while I was studying at University. The Northern Soul scene was part of my world from a very young age, so I just photographed that because I had a love for it. After I graduated, I began to photograph for magazines like Sleazenation and eventually i-D and The Face, that was my entry if you like, into that world. It was great, it was really good, I was beginning to be part of that photographic world and it’s not necessarily an establishment, but I sort of developed a reputation of photographing subcultures, style and kids out and about having a good time.

So how did you initially become involved with Sleazenation?

I blagged my way in, they were based behind Kings Cross. I can’t remember what it’s called now the street up there, but I went there and I just knocked on the door and someone let me in, I think it was Steve Beale, the editor of the time – It was just mayhem in there, it was brilliant.

So, I kinda blagged my way in, I saw one of the guys had my photos on his desk, I’d sent some photos out to a few different magazines. I said: ‘Oh well they’re my pictures there’ and he said: ‘Oh well I really like these’ and that was it from there on in. He just said: ‘Here’s some film, go and photograph this happy hardcore event on Saturday night in Tottenham, this is the address and bring the film back on Monday and we’ll get it processed for you.’ It just worked like that, it was kinda haphazard and it was wild as that.

From there on in I photographed for them every week, I was travelling up to Nottingham and photographing heavy metal kids, I was down on the South Coast photographing kids in Brighton and then I was partying. It went from strength to strength, became bigger and bigger until I found myself at the garage scene around ’98, and that’s where I felt more sort of at home as it were, because it felt like my people, really, garage.

Were there any inside scoops of what it was like to be at these parties first hand?

I don’t know, I can’t really explain that because I’ve been partying all my life, I just got back from partying with my friends. So, I don’t know, I’m not a massive cainer or anything, but I’ve spent a long time on the Soul Scene, I was there in Ibiza in 1989, we were involved in house music when I was 14/15 in Newcastle. I’ve always been interested in music and that movement, style and how it all brings people together. Garage was just a lovely moment, where it all just made sense. I was like yeah this is a bit of me you know, we can get along me and garage, so this is great. That really worked well, and I’m really grateful really for the time spent on that scene – it was mega.

What was the best garage rave you went to?

Oh, Twice as Nice is always the favourite for me, I always loved that, but probably one of the first Twice as Nice sessions down at the Colosseum, Colosseum ’98 Twice as Nice. Another good night, I wasn’t necessarily into Drum’n’Bass or Jungle, was Metalheadz on a Sunday. There’s too many to mention, but for me, the biggest nights were the soul nights at Blackpool Mecca reunion in ’90, that was a highlight.

So how do you think British youth culture has changed from when you first started photographing it?

It moves a lot faster because people are more aware of it through digital and social media, people are more aware of what’s going on and are more connected. We had to go out of our way to find each other to connect if we were into certain a style or type of music. You might see people knocking around town that had your kind of look, or were a mod or something, but you might not know them, so you’d think ‘oh my god he’s a mod too, that’s great! One day I’ll pluck up the courage to say hello’, or sometimes you’d connect straight away or there was a kid at school who was a mod and you’d just got on.

Now, you can probably read a million articles on Northern Soul or the mod movement and understand what it is very quickly, where we had to pass around a rare book or something – To learn about that scene and the history of where it came from, what it meant to be a mod and then you could get excited about it and find out more about style, and let your style develop and then you met a like-minded group of people and then you all started doing it a bit more. Now it happens a lot quicker, it manifests a lot quicker, sometimes it probably doesn’t have as much time to develop, but in other instances, things bubble under and people retain their autonomy and it might last a bit longer.

You were saying about the excitement of seeing someone and thinking ‘yes they get me to’, do you think that’s what created the shared explosion of love for the rave and UKG culture?

Yeah, I mean with rave it is probably something a bit different because house music had been bubbling under for quite a while since the mid-eighties, and that’s when soul music was also very popular on the dance floor. It was a very contemporary soul sound and the sound of black America at that time, so Garage was born out of that, but it became more British. I think it was that British sound, the post-soul to soul sound that helped develop people like MJ Cole and helped to develop the sound like Mike “Ruff Cut” Lloyd and Tuff Enuff used. The sound developed into something that was post-house music, something that was more British with a driving bassline and that amazing sort of skip of the high-hatch and the sampled locals that we all love. Show me someone that doesn’t like Garage, I can’t think of anyone and if they don’t like garage we’re probably not going to get along.

It the last ten years, in London especially, music venues and clubs have been butchered –

Good, fucking close them, close them down. Close them down because the world is changing, and that’s fine. What’s going to happen when they close down is that you’re going to get something more interesting popping up elsewhere, I mean yeah big established night-clubs and bars they’ve got a shelf life haven’t they? Do they have to stay around forever? You know nothing lasts forever, that sounds like death to me I’d rather have something new popping up, finding a different location somewhere else that we’ll all have to try and have a look at and learn about. Going to the same place all the time stinks doesn’t it, I never want to do that. You’ve got to find something new, let them die out and let’s have something new, show us what you can do and British kids are good at that – they’re good at reinventing and finding something new and creating something, and long may it continue because I don’t want it to be like the same place every time you go out, its crap.

Basically from what you’ve said about how kids are very good at finding things to do to avoid stagnation of nightlife, do you think this is why there has been such a resurgence in the sub-culture, for example like The Rave Today exhibition, because people are going back to the past to look for something new to happen again?

I think they’re always are, kids go raving at festivals now don’t they. If you want to go every week then I’m sure people will find a way to do that, we did, you don’t want to be vicariously living it out in the past either do you. It’s nice to see these moments, and these times we’ve done already, but I’m always looking towards the future really, and I’m old enough to know better.

How did you find the transition from UKG scene to Grime?

I kind of ignored it really, and then Mike Skinner who I was working with reintroduced me to it, and said check this out you should be looking at these kids and then I started photographing them, their big brothers and sisters had been at the garage raves, and they were trying to do something different.

What are you most excited about for the public to experience at The Rave Today Sweet Harmony exhibition?

Hopefully, they’ll have a rave! The pictures are going to be fantastic, I’m looking forward to seeing all the artists involved obviously, there’s some really great people involved and some great photographers and artists, I can’t wait to see Dave Swindles, Derek Ridgers among others. I’d be interested to see some events where we can hear people talk and also get involved with how the music is made and maybe even do some after-hours raves and stuff like that, that would be more like it.