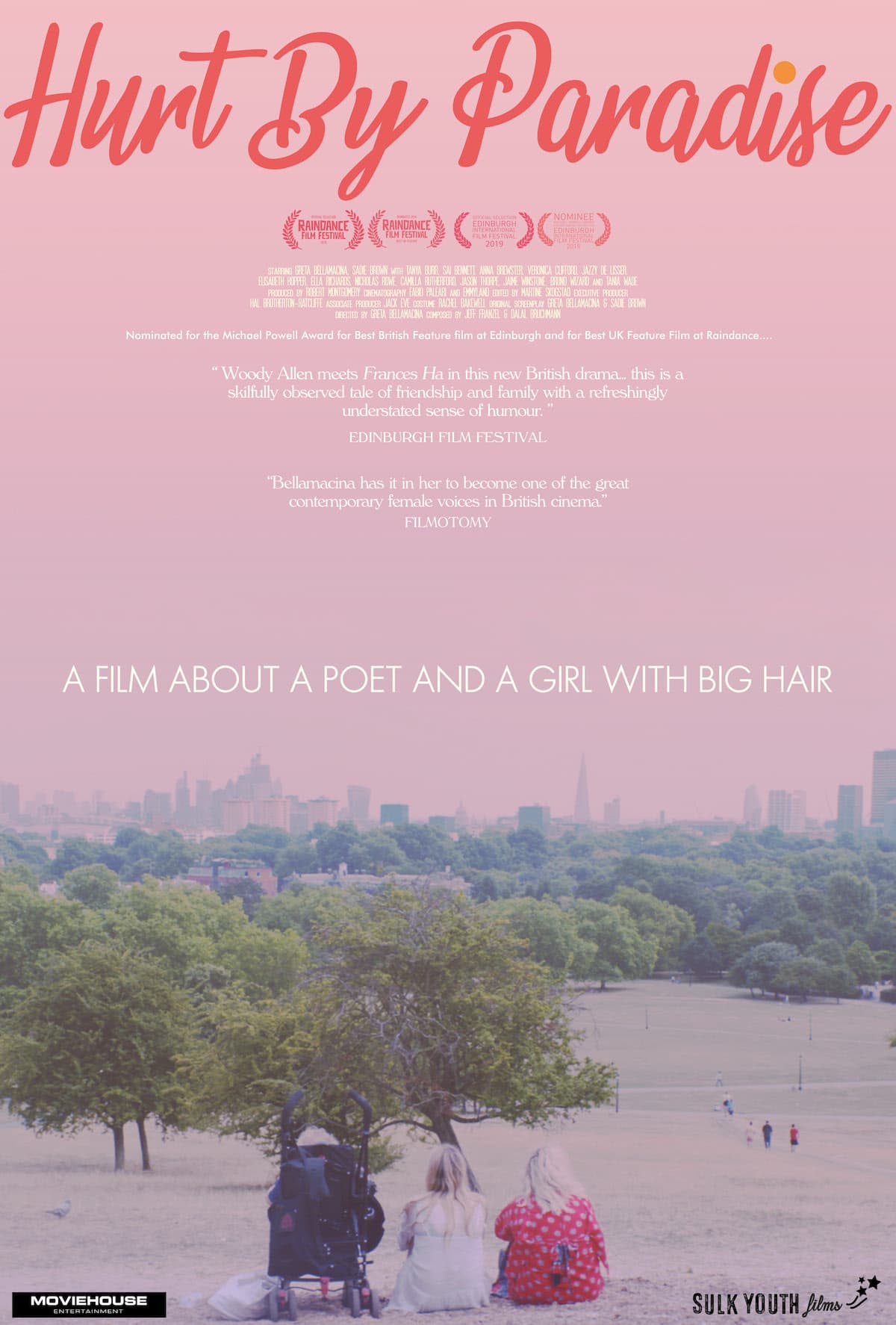

Family Affair: Greta Bellamacina on debut feature ‘Hurt by Paradise’

Wowing critics on the festival circuit, Greta Bellmacina’s debut feature Hurt By Paradise scooped up nominations for Best British Feature Film at the Edinburgh International Film Festival and Best UK Feature Film at Raindance. Shot on a budget of just £75,000, it follows struggling poet and young single mother Celeste as she grapples to get her work published and track down her estranged father, leaning on her babysitter-best friend Stella for support. With light and airy shots and ponderous, poetic voiceovers taking us inside Celeste’s innermost thoughts, Hurt By Paradise is both aesthetically gorgeous and a reminder to keep dreaming, no matter how much reality gets in the way.

Below, we talk to Greta about female friendship on screen, celebrating alternate family structures and what needs to change to support British indie cinema.

Can you tell us a bit about your creative background — you’re best known as a poet but I know you’re also a model and actor as well as a filmmaker.

I have always been interested in words as truth. Poetry is the language I feel most comfortable speaking in. It is complicated and profound enough to reach your soul in a few words. I sometimes walk around the Brompton Cemetery and read the lines of poems which have been buried in the stone for centuries. They get straight through to me every time. Acting and filmmaking have been a way to explore language and words in a different way. I think we are all acting most of the time, but poetry is when we stop and speak honestly and let the broken light pour out.

How does being a multi-hyphenate affect your creative process?

I’ve always found comfort in performing, growing up I spent all my weekends in youth theatres. I used to write and perform plays for The Hampstead Youth Theatre. I would spend hours trying to understand all of it: writing the words, planning the stage exits and trying to understand the characters. At drama school, I had endless notepads of scribbled character notes. I would watch all the old stage footage with the characters I was trying to convey hoping to discover something new, so that was all the weekends of my youth. Poetry was always something I did privately. It was another sort of freedom. When I write a poem I usually speak it aloud. I say it as if I were performing it, under my breath, like a little musical melodrama. Hurt By Paradise is very much a meeting of these two spaces.

Has growing up in London influenced you?

I guess it has subconsciously. I wanted the London you watch in this film to be very much the one you see when you walk home from a night out. The picture of the streets and houses at the back of the night bus home. The London that feels familiar but also far away and mysterious. A lot of the poetry you hear coming from [lead character] Celeste’s head is spoken in these moments, moments of dreamlike wonder.

I’ve read that you’re interested in John Cassavetes — what other filmmakers have inspired you?

I am a big admirer of Joanna Hogg’s filmmaking, her last film The Souvenir was playing at Edinburgh Film Festival the same time as Hurt By Paradise. I think there is an intense realism to all her films. She also uses actors and non-actors within her films, which I like. Jim Jarmusch does it in Coffee and Cigarettes. We wanted to do a similar thing in this film, by bringing together a team of great character actors such as Jaimie Winstone, Camilla Rutherford, Veronica Clifford along with people we have known and admired for a while, people who inspired us and held enough of a character to make them fit the world we were trying to create on camera. I have always loved Terrence Malick films— to me they are utopia.

Before Hurt by Paradise, you directed The Safe House: A Decline of Ideas, about the threat to public libraries. Why are public libraries so important to you?

I grew up going to my local library. It was a place of sanctuary and quiet riots. I wanted to make a documentary about the history of the library movement but also tell the stories of so many people who have benefited from these places. It was really heartbreaking seeing so many libraries around the country being turned into luxury apartments and gyms. Taking away a library really changes the face of a community and its ability to grow and self-educate and dream. We went back to the first public library in Scotland built by miners, in a small place called Wanlockhead. There was something very church-like looking up at this small library on the top of a mountain made out of wood from the hands of workmen for their children to learn and better themselves.

What were your inspirations for Hurt by Paradise?

We wanted to make a melancholic comedy about two women who keep failing to achieve their dreams but give their whole heart every day because that’s all we can really do. To show two women who are flawed and complicated but also innocent and big dreamers. To show the fantastic and the ridiculous in the everyday. There is a line in the film which Stella’s character says; “a failure is a winner who tried one more time.” We didn’t want the film to be driven by a major plot but by the hearts of these women instead.

There have been a lot of comparisons between Hurt by Paradise and Frances Ha. What are your thoughts about that?

I am a big admirer of Greta Gerwig especially her last film Little Women, I cried throughout the whole film. I guess there aren’t that many films centred around big cities where the two female protagonists are the main subject. The love story is the two women. Not the city, not the men but the women. The women are enough without any big grand effects and sweeping love stories. We consciously wanted to show a snapshot of these women’s lives and the city is sort of a part of their loneliness, but also their determination to fulfil their dreams. I wanted the characters to be a reminder of the early dreamer inside of all us in a new city no matter the age.

Why did you want to show what it’s like to be a single parent today?

I was keen to show a picture of a mother whose downfall wasn’t her situation as a single parent. I wanted this film to be the opposite of that. I wanted the film to be a bit more gentle and to depict a woman who was just doing her best coping without it being her main storyline. We wanted the two friends to sort of take on the responsibility of parenting this child without it being a huge drama because that’s what women have done for generations. There is a line in the film which says; “I don’t actually think you need a man to look after a child, but you definitely need two women.” It’s important to be positive about the idea that families come in all different shapes and sizes.

Your son Lorca appears in Hurt by Paradise and your husband produced it — how does this family dynamic impact the film?

Because we made the film for such a low budget this meant that we could have a bit more flexibility with the crew. We wanted them to feed into the creative process as much as us. Having Robert involved helped bring a more poetic vision to the film. A lot of the times when I was acting he would be on the monitor directing me. I think working with the person you love, means you are always trying to bring a certain amount of realism into the project with the protection of the other person. By the time we shot Lorca the crew felt very familiar we worked in small closed-off sets so it felt more like a strange game that being filmed. It was a privilege to work as a family, to have these memories together and keep close.

What do you want to see change in the British creative industries?

I think we need more support for independent films which are made for a micro-budget like Hurt By Paradise. We shot our film for just £75,000 but in cinema these days the phrase “indie” very much refers to a million pounds or more, whereas there are a lot of films made for much less which don’t stand a chance of being released. I think this is because there isn’t enough support from the industry to platform auteur films. There needs to be a new distribution model to release truly indie films in a fair way, because if not we are letting a whole load of unseen talent fall by the wayside.

What’s next for you?

I have a film coming out next year called Venice At Dawn where I play a sort of Bonnie and Clyde-type character directed by Jamie Adams, which we shot just before lockdown. It’s the second film our production company Sulk Youth has produced. We are also in the pre-production stages of a new film which I will co-directed with Robert Montgomery called San Valentino based in Italy about a mother and her three daughters. I am also working on a new poetry collection.

Hurt by Paradise is out in cinemas now. Check out screening information here.