Fashioning freedom

Fashion progresses at the peripheries of culture, in the spaces that steer clear of the mainstream and the commercial, until it’s eventually picked up by savvy fashion writers with their ears to the ground, then it transforms, morphs and subsequently breaks boundaries set by wider society.

Historically those spaces are often queer and hidden away from the general public. From the discreet areas of St Petersburg’s parks frequented by effeminate Russian male sex workers at the turn of the 20th century, as explored in Dan Healy’s 2001 book Homosexual Desire in Revolutionary Russia, to the U.S ballroom scene that emerged in the 1920s, to drag shows and raves, all the way up to the present day.

The current consensus is that fashion should be fluid, which has given rise to many gender-neutral brands such as Tanner Fletcher and Telfar, as well as endeavours by fashion giants like Stella McCartney, Marc Jacobs and Gucci. The demands for fashion to be this way have gone past individual experimentation and moved into a commercial arena.

“The gender binary isn’t just being unravelled right now for the first time. There are all kinds of moments throughout hundreds of years that we can pick out and think about in that kind of way,” says Zorian Clayton, assistant curator at the V&A, who worked on its Fashioning Masculinities exhibition. “All of the moments when men were more highly adorned than women, all wearing make-up or jewellery. I think it’s very important to keep reminding that there have been all kinds of styles and approaches to fashion that don’t fit today’s rigid idea of what the gender binary has always been.”

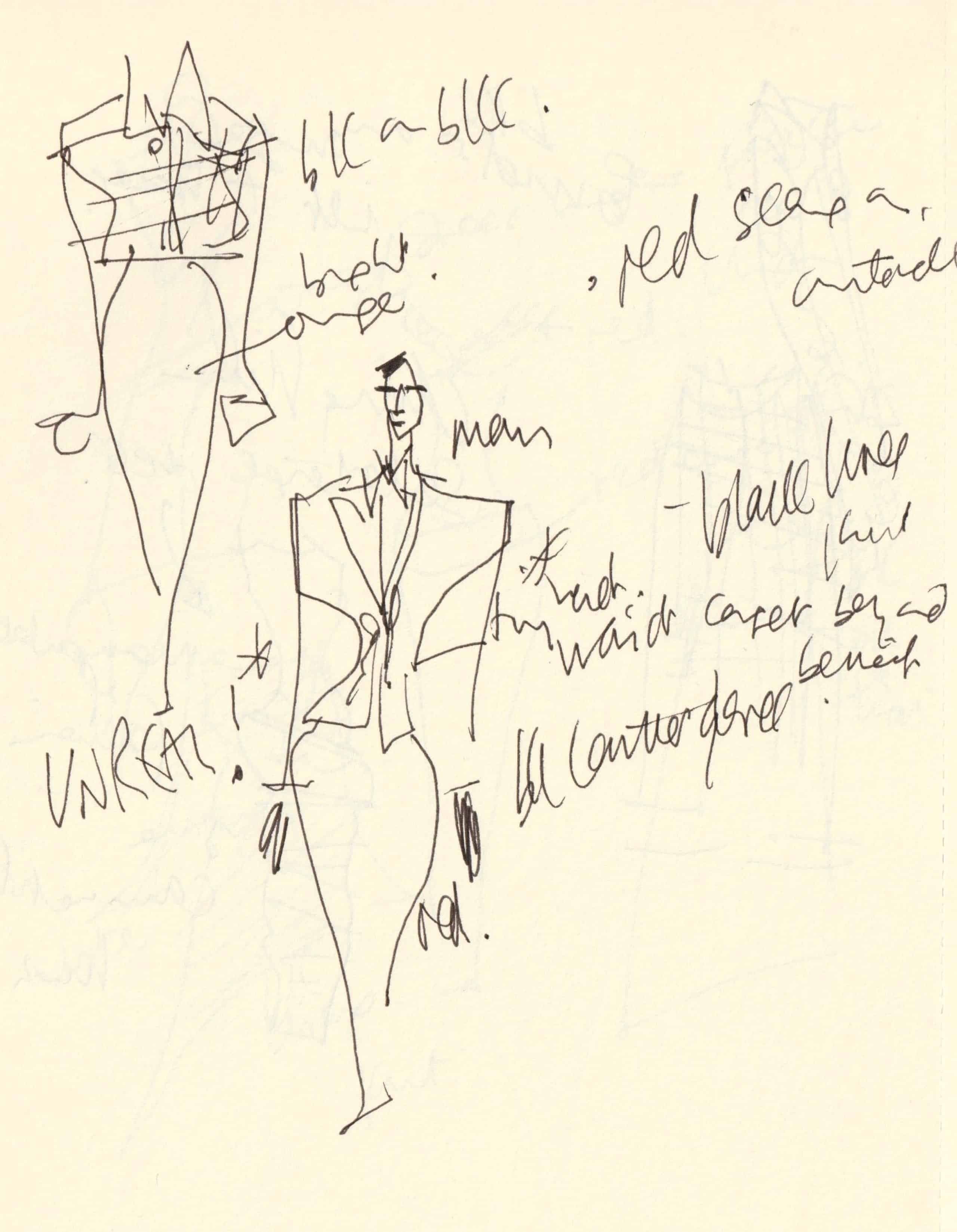

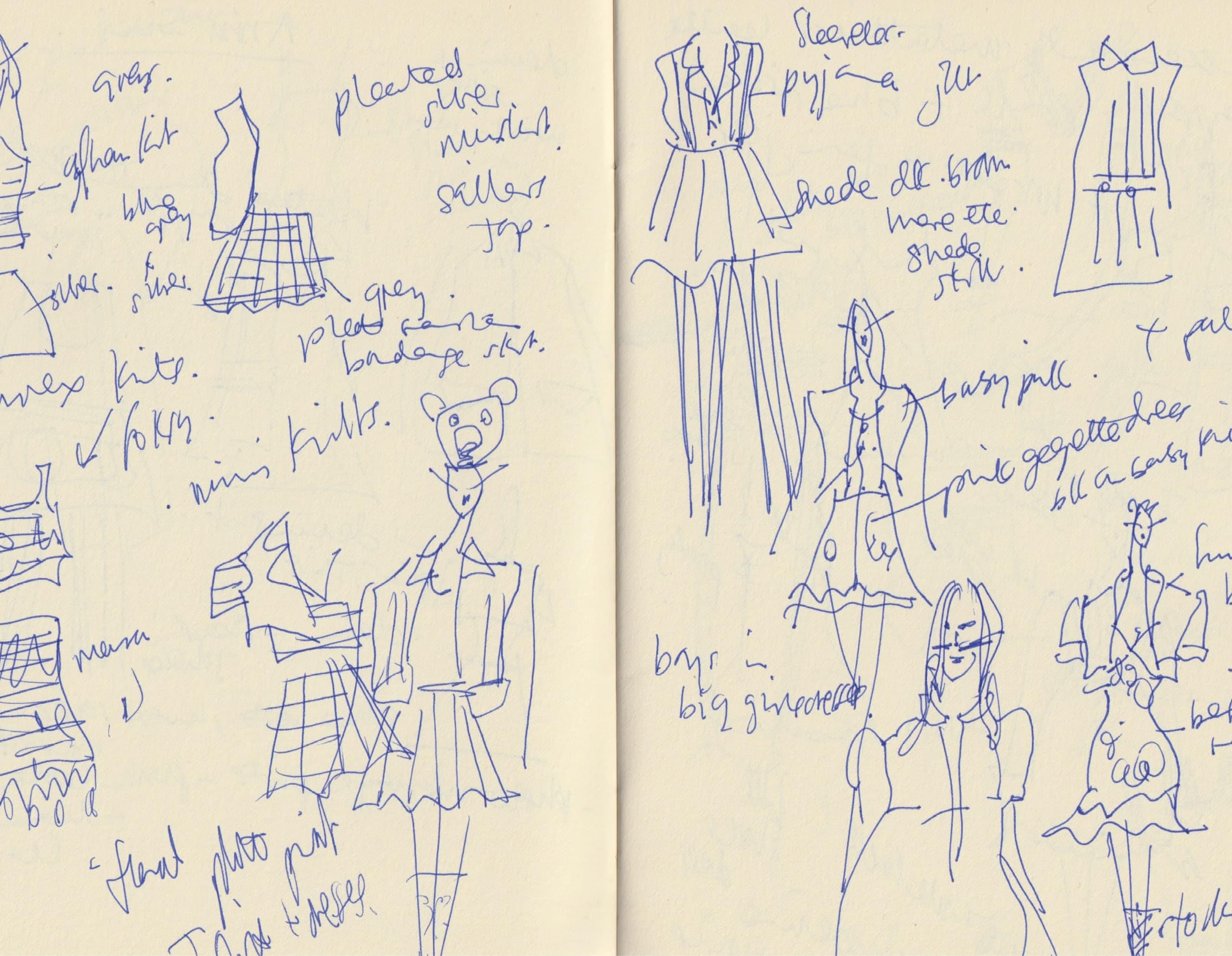

Iain R Webb, veteran fashion sketcher, writer and curator, agrees and pinpoints the moments in contemporary fashion history when the gender binary was being erased in the commercial arena. “The vogue for androgyny, as gender fluidity was then termed, began in the 1960s, when male mod ‘faces’ – the trendsetters – wore make-up, while some female mods favoured cropped haircuts, trousers and flat shoes,” he tells me. “In the 1970s, men scissored patterned chiffon and satin dresses from the 1930s and ’40s to wear as shirts. In 1975, designer Mary Quant even brought out a make-up box for men. From the 1980s onwards, Jean Paul Gaultier was a major inspiration and influence on gender fluidity. Right from the start his collections embraced difference and challenged established social norms – not least by putting men in skirts and ‘beefcake’ men in corsets. Ostentatious, opera-length evening gloves were a must for Gaultier’s man.”

And for years gender-fluid dressing and indeed queer dress has been used as a personal form of self-expression, but for a time, fashion and dress were tools of subtle reveal and more to discreetly present sexual desires rather than express an identity.

One obvious example of this is the Hanky Code, used by gay men during the 1970s and 1980s, and Shaun Cole’s 2000 book ‘Don We Now Our Gay Apparel gives quite an insightful explanation: a white hanky worn in the left-hand back pocket of a man’s jeans or trousers meant “jack me off”, but worn on the right-hand side meant “I’ll do us both”. A mustard hanky on the left meant “has 8 inches or more”, and on the right meant “looking for a big dick”. An orange one, worn on the left, meant “anything but top”, and on the right “anything but bottom”. You get the gist.

However, those methods of signposting aren’t needed nearly as much now in most countries. Fashion in queer culture is about claiming that sexiness and sexuality as part of what we wear and how we wear it, it’s not just a means for copulation and reveal.

Take Lynn La Yaung, for example, freshly graduated from Central Saint Martins, who designs clothes for the dark, intense environments of techno events in London, the kind where the best nights are on a Sunday and cameras are banned. Before we call, I scroll through his Instagram (@l.l.yaung): his latest clubbing look shows him in a beret, shoulder bag and tank top, with his hips and V line leading into a miniskirt, revealing a bulge hanging insouciantly lower than the hem. It’s sexy, bold and fearless.

“I’d always wanted to dress the way that I dress now but I didn’t feel like I was in the right environment to do it,” he says, sitting topless in his bedroom-cum-studio, exposing his gothic spider web-type tattoos. “I think male and female is an old concept now when it comes to gender. I think every silhouette needs to be worn by everybody without it being so boxed. For my graduate collection 2.0, I wanted to redo it in a way so it doesn’t feel so masculine any more. I wanted to break down the silhouettes that I’d done and adapt to the current me.”La Yaung is just one of many young creatives whose view on their own self-expression has been shifted by the possibilities of different communities. Through frequenting events that have become safe havens for LGBTQIA+ folk, the ability to dress, design and wear whatever you want is not limited by anxieties about how others might perceive you. Instead it’s a celebration – a way of pushing your own fashion boundaries that has seeped into everyday life.

And so, in 2022, pearls and painted nails, previously considered to be staples of feminine attire, decorate young men around the world. Some of today’s biggest designers – those thought of as genuinely boundary-breaking – like Harris Reed and Grace Wales Bonner, create clothes that are fluid throughout. The actor Billy Porter was responsible for one of the most memorable moments in fashion in the past decade when he wore a Christian Siriano black tuxedo dress with a cinched waist to the 2019 Oscars, sending social media into a frenzy. US Vogue’s December 2020 cover – Harry Styles in a custom Gucci dress – had a similarly seismic effect. These are all examples of fluidity and queer identity pushing through from the background into the fore. But why now? What is it about the time we are living in that has propelled fashion into a period of ultimate freedom, giving us complete liberty over what we want to wear and how we want to wear it, and why has queer dress leapt out of certain spaces and into the mass media?

“I think there’s just an accumulation of confidence now,” says Claire Wilcox, senior curator of fashion at the V&A and co-curator of Fashioning Masculinities. “There’s also been an accumulation of confidence in areas beyond fashion – visibility, agency. Social media has really – OK, it has negatives – helped to encourage bravery.” And her V&A exhibition, which was five years in the making, journeys into the far reaches of different masculinities, displaying clothing and identities through centuries divvied up into three categories: Undressed, Overdressed and Redressed. It has been praised for its commitment to trans visibility on the topic, but has been described to me by a number of queer people as “one-dimensional”. It seems that exploring masculinities essentially through more of a queer lens overlooked numerous areas of potential interest, like the role of hip-hop, baggy jeans worn hanging off butt cheeks, and what the likes of NBA star Dennis Rodman did for fluidity. But inevitable critiques aside, the mere existence of the exhibition is testament to this new age of putting fluidity and queer identity at the centre of contemporary fashion.

“Look at how far non-binary identities and understanding and discussion have come in just five years,” Clayton says, “like the rapidity with which so many of the designers and the artists have come out with different, new identities that perhaps weren’t so widely understood even five years ago.”

“What’s happening today is that it’s being celebrated. It’s not threatening and it can coexist alongside tough denim or leather or whatever,” Wilcox adds. “And I think that was the aim of the show, just to show that there are many, many interpretations of masculinities. And within that there are infinite possibilities of permutations, and it’s really down to designers and wearers and society to have to embrace and welcome this but also to understand, so it’s not new.”

At the heart of Fashioning Masculinities isn’t just an exploration of masculinity, it’s fluidity and the role that queer culture and identity has played in allowing fashion to open its boundaries throughout history. Speaking with the curators, it feels as if right now is a time of total celebration and freedom. However, outside the conversation, it surely can’t be said that fashion is fully free; maybe it’s all a bit of romanticisation. For example, you go out on a Friday night, as Clayton mentions, and the gender binary isn’t being thrown out right, left and centre – there’s still plenty of work to be done before fluidity isn’t seen as alien or out-there in society.

So even if this is a time of celebration, a lot of celebrations are characterised by some form of hardship. This time of fluid fashion that we’re living in now is only becoming joyful because of historic pain; you don’t have to go much further than the door in an LGBTQIA+ space to find someone who has been verbally or physically assaulted for the way they dress. Fluidity has been a risk and queer subcultures crossing wires with the commercial and wider culture has been a dangerous act – one that can get a queer person beaten up, but will simultaneously feature in some of the biggest magazines in the world.

Still, even though it might feel as though queer identity has one foot firmly in culture and the other plunging in and out of abuse and inequality, what right now does symbolise, if it isn’t celebration, is budding visibility. For example, at the end of this high-brow, meticulously curated exhibition at the V&A, the final piece of writing reads: “Don’t be scared to embrace the femme/whether you’re he, she or them.” Drag queen Bimini Bon-Boulash’s adored quote from series two of RuPaul’s Drag Race UK, as well as her own eminent presence in society, are emblematic of the developing trajectory. Drag queens aren’t just staples of piss-up brunches on a Sunday anymore, they’re renowned figures and celebrities. Designers creating gender-fluid clothing are no longer creators for a niche market, they’re on the covers of fashion magazines around the world. And fluidity is not constrained by those – mostly LGBTQIA+ folk – who want to experiment with self-expression in safe spaces like raves. Now, even cishet men aren’t afraid “to embrace the femme”.

Hoping that one will lead the other, queer culture’s developing intrinsic relationship with men’s fashion and how it has been liberated by queer dress will knock the remnants of anxieties about shifting fashion into submission. And soon, fluidity may not just be at the centre of the conversation, but will sit firmly at the centre of how we live. “I’m truly excited about the future of men’s fashion,” Webb concludes. “There are years of catching up to do with womenswear… so many tremendous possibilities.”