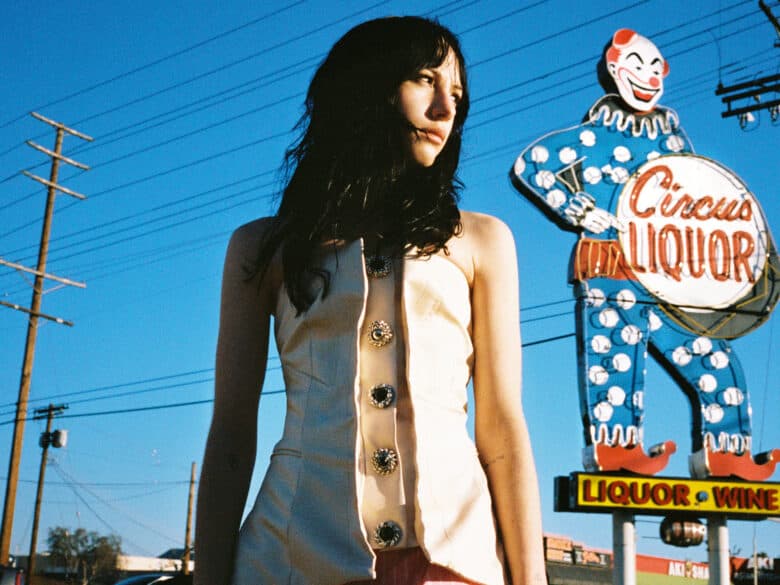

Fatima Al Qadiri is known for grime-infused compositions that quiver on a tightrope between music and conceptual art. Whether it’s inhabiting and scrambling Chinese stereotypes on Asiatisch, a 2014 LP that unpacks Western Orientalism through its own one-dimensional imagery; or the politically-orientated Brute, looking at US police brutality and neoliberal fascism; she approaches her primary medium with an ideological robusticity seldom seen in her contemporaries. Via deceptively airy arrangements she uses her craft to open up spaces of confrontation between entrenched ideology and more progressive modes of perception.

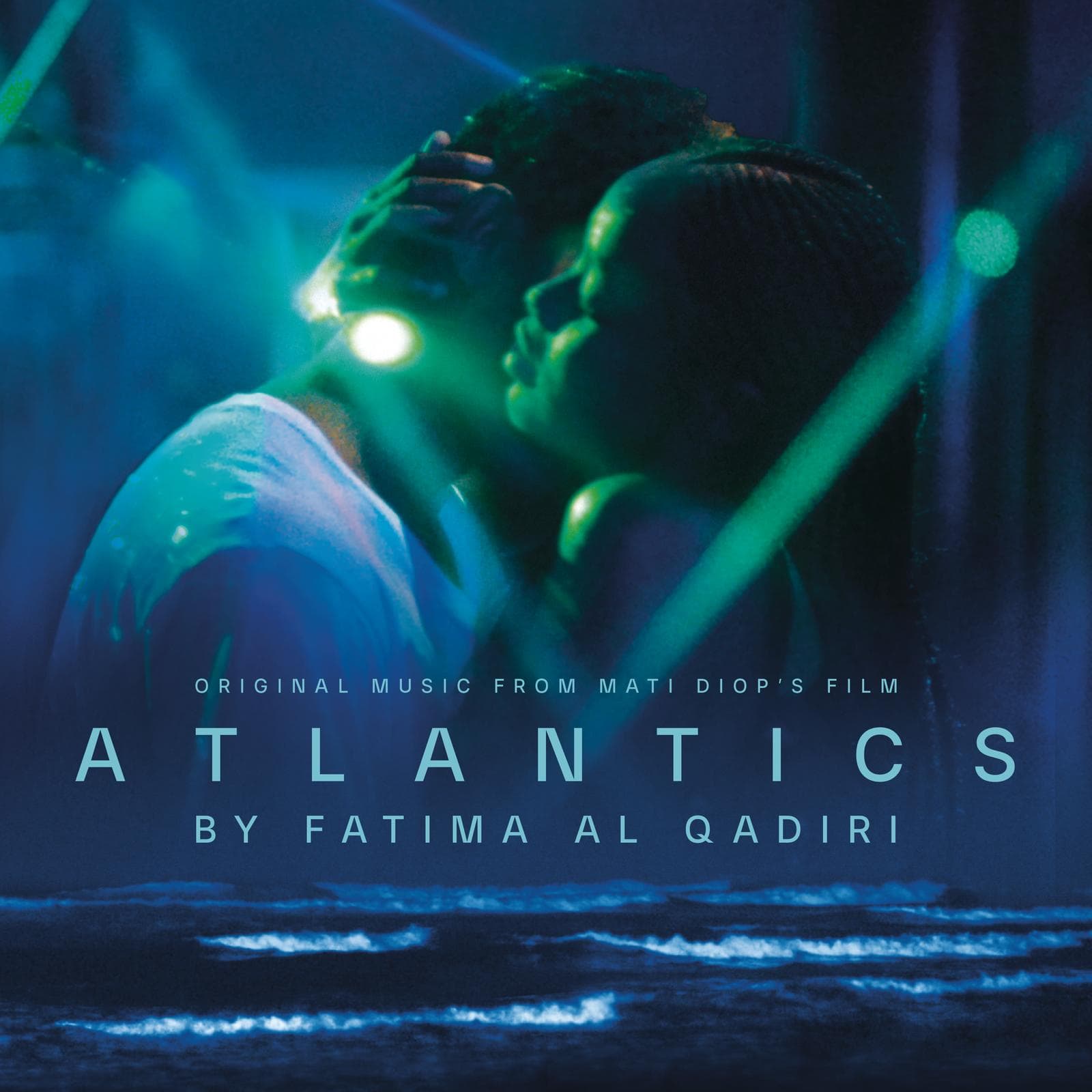

Most recently, the Hyperdub stalwart has been drafted in to provide the score for Mati Diop’s Atlantics, a paranormal drama that scooped up the Grand Prix at Cannes. As someone whose practice revolves around a close symbiosis between content and concept, the collaborative art form of film-scoring — an exercise where the composer simultaneously interprets and responds to a cinematic work — feels particularly well-suited to Al Qadiri. Atlantics itself, lacking the art world gloss we might associate with the musician, doesn’t automatically seem like a natural fit. However, on closer inspection, Diop’s blend of urgent social commentary and supernatural plot points seem to mirror Al Qadiri’s disorientating creations.

By Al Qadiri’s own admission, her involvement in the project was largely due to Diop’s insistence. “Mati was very persistent in her vision that I should compose the score,” she says. “Her insistence was endearing.” However, there was also an added connection: the Kuwaiti composer spent some of her early life in Senegal, where Diop’s drama unfolds. “I have to say the Senegalese angle was also compelling since I was born in Dakar,” she admits. Diop’s insistence paid off: Al Qadiri’s oneiric, brooding score settles like mist over the action of the film, its abstraction and discordant sounds helping to accentuate the paper-thin boundaries between the lands of the living and the dead.

As someone who’s previously admitted to a belief in djinns, spirits that roam the Earth, Al Qadiri was able to slip into Diop’s magical realist mode. “The tension between the supernatural and real [explored in the film] exists very strongly in Kuwait, which is where I wrote the score,” she says. “I find it difficult to put into words to be honest but I was writing between 11pm and 5am every day so the score was done in the spooky hours to get my head into that zone.” Immersing herself in the mood of the film, Al Qadiri drew on a background of musical improvisation for an instinctive scoring process. “I would loop the scene in question and watch it while improvising until I got the right vibe, then filled in the details,” she explains.

The artistic flair of Al Qadiri’s score — which provides another layer to the film, rather than limply existing on the background — is emblematic of a wider shift within the industry. Moving past lacklustre and (sometimes) cheesy scores, filmmakers are drafting in experimental composers to help elevate their work. Recent years have seen Mica Levi’s acclaimed compositions for Under the Skin, Jackie and Monos, Ryuichi Sakamoto’s heart-pounding score for The Revenant, and Oneohtrix Point Never’s anxiety-ridden soundtrack for Good Time. “I’m glad scoring is having a moment because it seemed for a while that scores were becoming an afterthought or the usual safe and bland palette,” says Al Qadiri. “Scores naturally have always been important but they ultimately reveal which director is a bona fide music nerd and which has other priorities.” For her, the best scores are ones which feel like an intrinsic part of a film’s fabric, no doubt explaining her approach to Atlantics. “Akira and Blade Runner are my two favourite scores of all time. You can’t imagine either film existing without their scores.”

Whilst Atlantics is notable at a sensorial level, both for its score and radiant cinematography courtesy of Claire Mathon, there’s also an undeniably political element. With documentary-like precision, Diop hones in on issues of social inequality and gender politics in Senegal and, most poignantly, explores the lost lives of migrants making the sea crossing to Europe and the impact on those they leave behind. With European and US governments taking an increasingly aggressive anti-migration stance, it is increasingly important for creatives like Diop to counter the views of scare-mongering politicians to demonstrate that migration is not only a humanitarian issue but also a natural facet of human behaviour. “I think it’s important for art to tell contemporary stories and perspectives that are not widely seen,” Al Qadiri says. “The politicisation of migration via ethno-nationalist perspectives is a fairly modern phenomenon. The thing with migration is it’s as old as humans.”

Atlantics streams on Netflix from 29 November. Al Qadiri’s score is released via Milan Records/Sony Masterworks on 15 November. Lead track ” Boys in the Mirror” is out now – listen below.