Fear and fantasy in Las Vegas: photography by Hunter Barnes

Motivated by the aim to understand and bring awareness to communities often ignored as well as misrepresented by mainstream America, Hunter decided to document them in as honest a portrayal as possible. Starting in his early twenties, the photographer began to immerse himself in the cultures he was intrigued by: from his Redneck Roundup series of Old West communities, to inmates in California State Prison, Hunter lets his curiosity carry him.

Whether it be months in the Appalachian Mountains or four years spent with the Nez Perce tribe, Hunter fully submerges himself into their spheres, actively engaging in the culture and finding the truth beneath. For his latest project, Hunter has delved into maybe one of the most preconceived places he’s explored yet: Las Vegas. Once the embodiment of the American Dream, built by the original dreamers, it has since evolved into Sin City, a place of broken dreams and empty wallets. Focused on the spirit of old Vegas, his shots capture an almost faded era, through the old timers themselves and the remnants of their world. A rare kind of artist, one who partakes as much as he takes in, Hunter commits himself to the reality and commits his subjects to film before it’s all just a fantasy long passed. As he promises us, it’s utterly worth the commitment, “I think real is out there, you just have to search for it.”

You shoot exclusively on film, is that a reflection of your perception of the modern world?

Yeah, I shoot only film, and then I print them in my dark room at my studio; I mostly enjoy the process of it. But I’ve always felt like film has soul: it’s a different style of shooting, a slower process. My whole process is slow compared to the digital world of shooting, I go and live with people for a long amount of time and get to know them. So I think there’s something relaxing about film cameras, the way they sound, the way they wind – it reflects the intimacy of my time with the people I shoot.

What has photography meant to your life?

It’s changed my life; it’s been an extension of my life for 20-odd years now. It’s opened up so many doors of experience for me: from places I’ve travelled to people I’ve met, all of that just would have never happened if it wasn’t for taking photographs.

How do you choose the communities that you immerse yourself in?

Strangely, nine times out of ten it’s something that occurs naturally. Somebody will tell me about a place they’ve heard of, or tell me about someone they know and I’ll be intrigued. It’s strange how that happens, but it just starts to open itself up. Sometimes I’ve just had to drive out there blindly, and usually when I do that I don’t even take a camera with me. I take some of my photos or some books and I explain to them what I have in mind. A lot of the time there are weeks spent without any photographs being taken, just so I can get my head around who they are and so that they can understand my intent.

What first attracted you to Vegas as a place to explore?

At the dinner table after my book opening with Tony [Nourmand] from Reel Art Press, somebody just casually mentioned Las Vegas, and I thought, “What would I want to do with Vegas, it’s so done”. To me then it was just an empty place where people went to gamble and binge drink. So that’s what I said, and this guy slapped my leg and he said “Char, man!” and I said, “What’s Char?!” He told me that his nephew Char owns a cigar lounge out there, and that lots of the real deal old timers hang out in the day. He said, “I really think you should just book a flight and see what you think.”

And so you did?

So I did. When I got out there sure enough it was like going back in time, a place full of all the old timers from Las Vegas just hanging out, smoking cigars. Now that they’re pretty much in their 70s and 80s, it hit me when they started telling me their stories that a lot of that generation weren’t around anymore, and they’d never had their photos taken.

Do you think that people outside of it have a warped perspective of Vegas?

Definitely. Although I guess it’s the same with a lot of places” people have judgments before they’ve even spent time with people there. That is why I research too much before I go into these projects, so that I don’t have preconceived ideas.

A lot of it is from pop culture, it’s changed a lot from Scorsese’s Vegas to now…

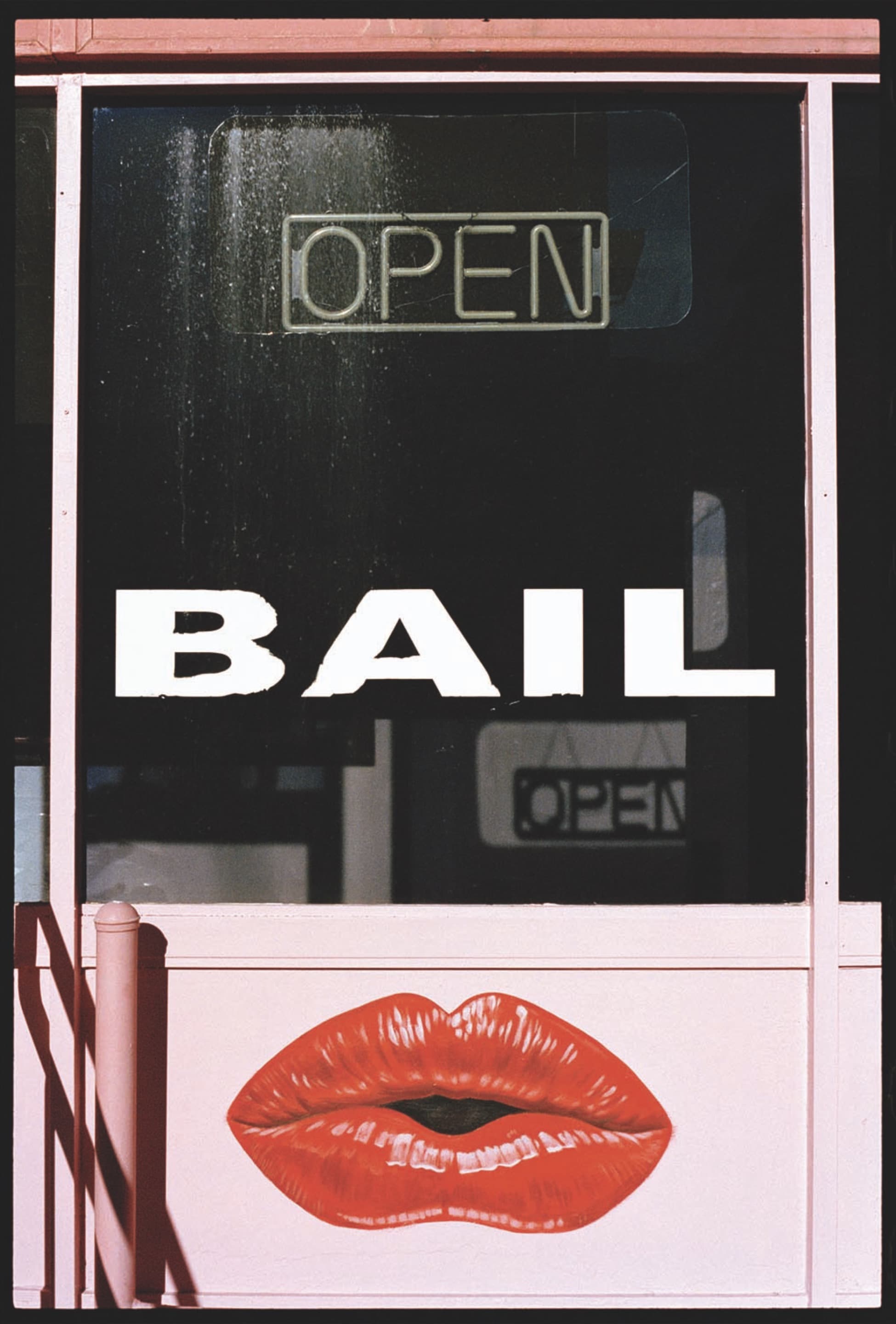

Oh exactly! It’s wild how completely different it sounds in the stories I was told. It was funny because I was just in their homes looking at their photographs, and you realise that these people are the real deal. They’re the ones who built Las Vegas, who made it into that pop culture stereotype of past. One night, they took me out and it gave me the idea of the title – Off the Strip – because originally all the casinos were off the main strip, now they’re all over and it really made me understand the difference. Casinos back then were independently owned, which gave them a very different atmosphere to now – it’s all so corporate now. It really is a different time: what was once a tight knit community where everyone knew each other, has changed into something very hollow now.

How did you capture both sides of the picture? The hollowness and the history?

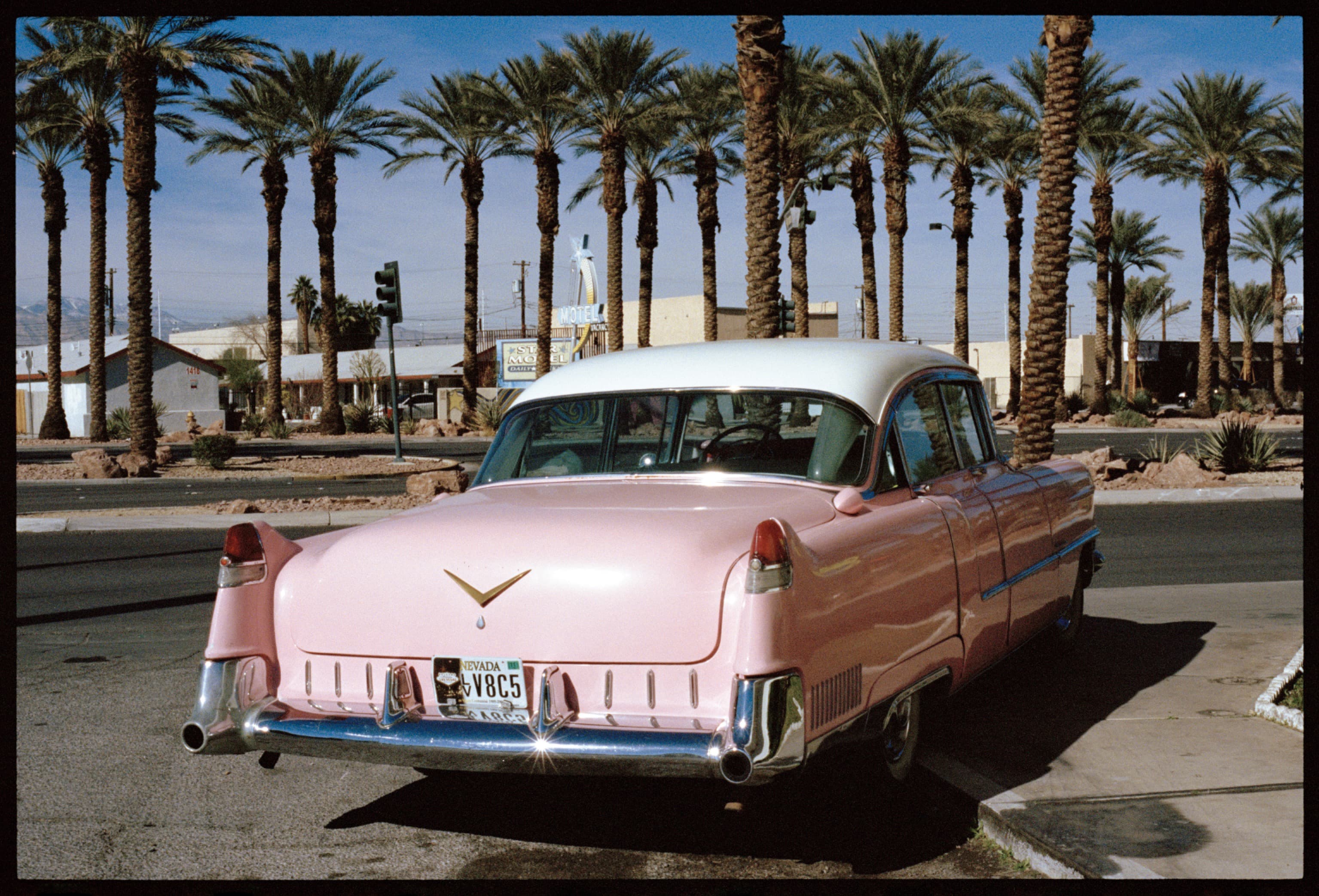

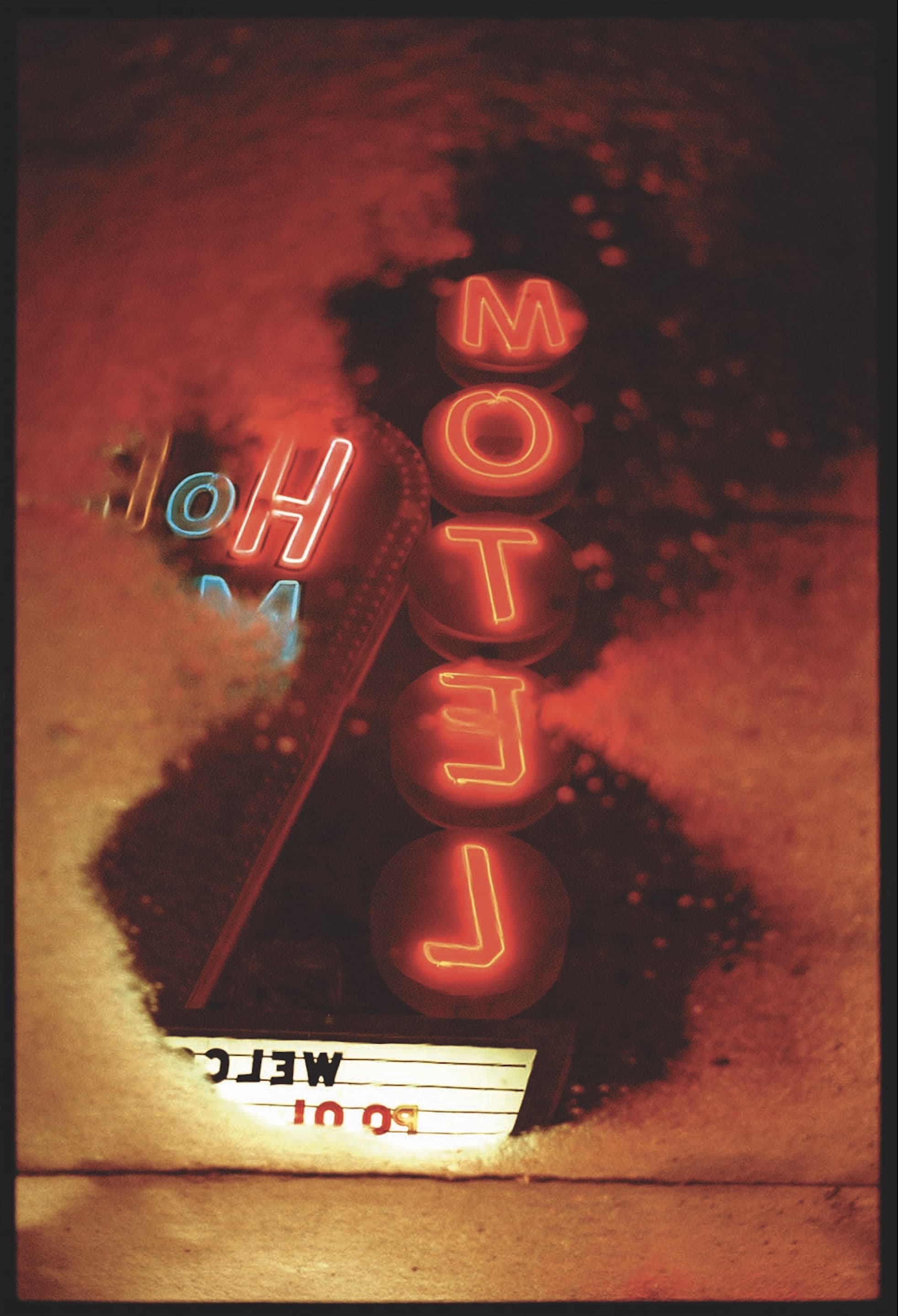

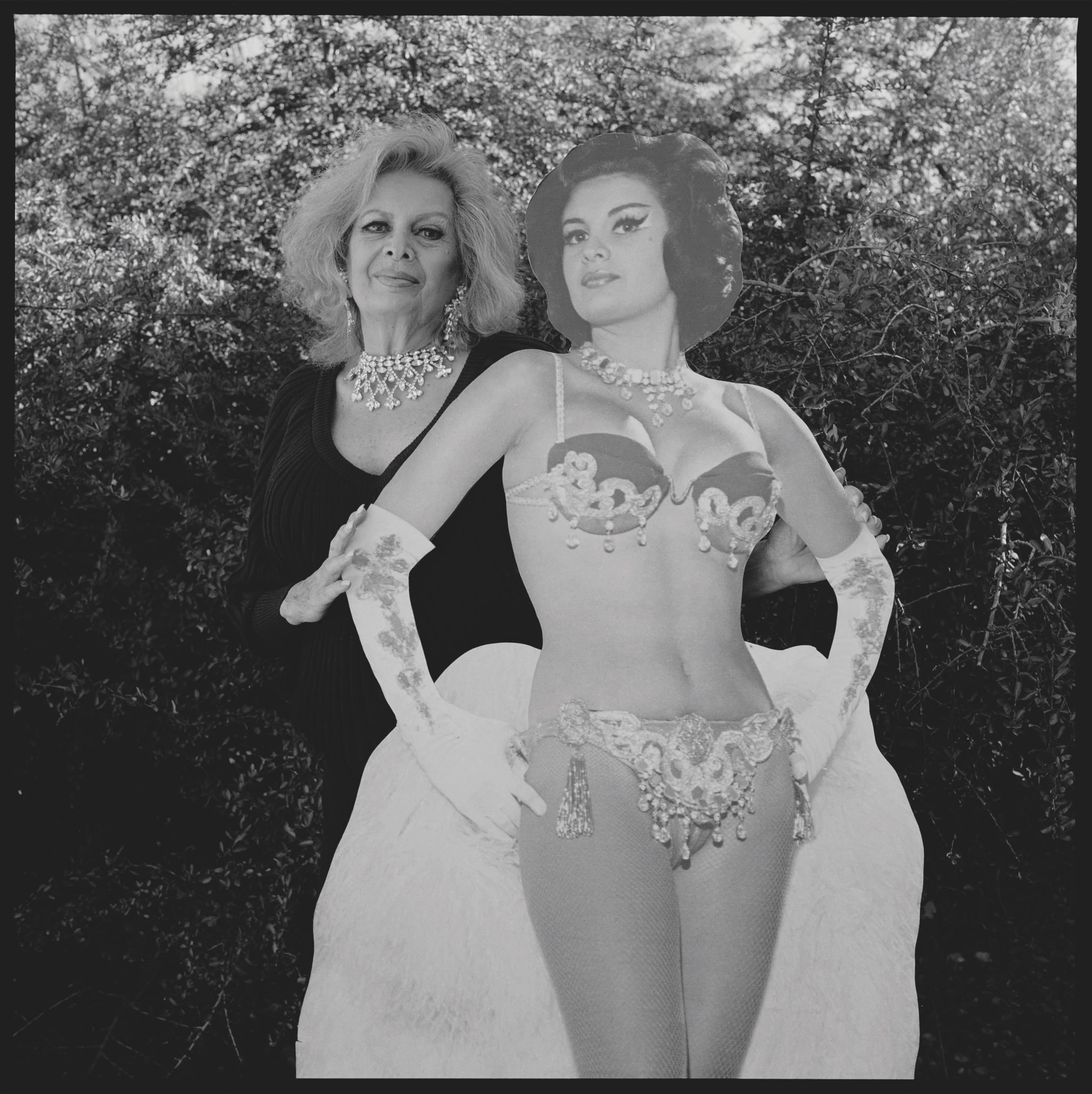

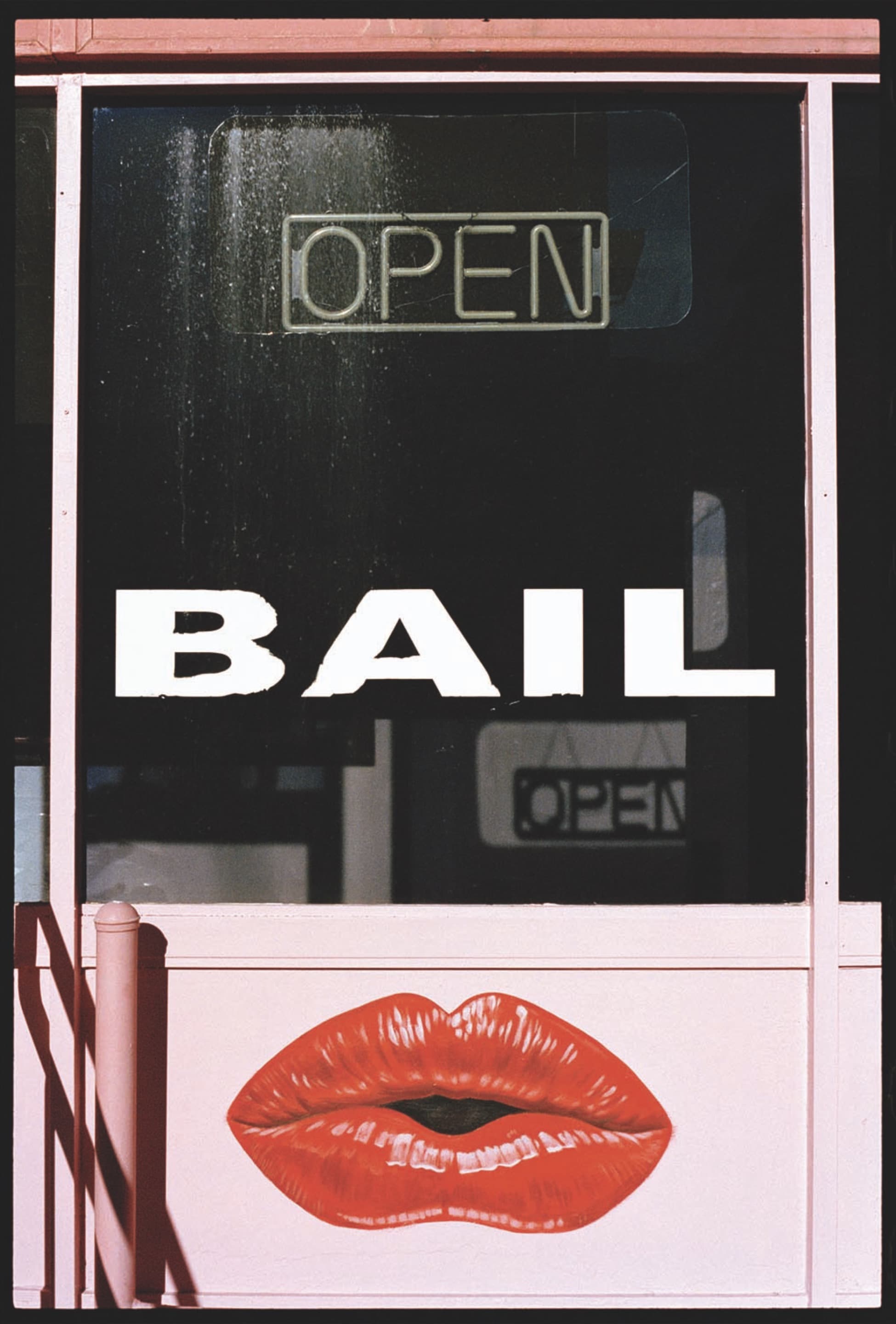

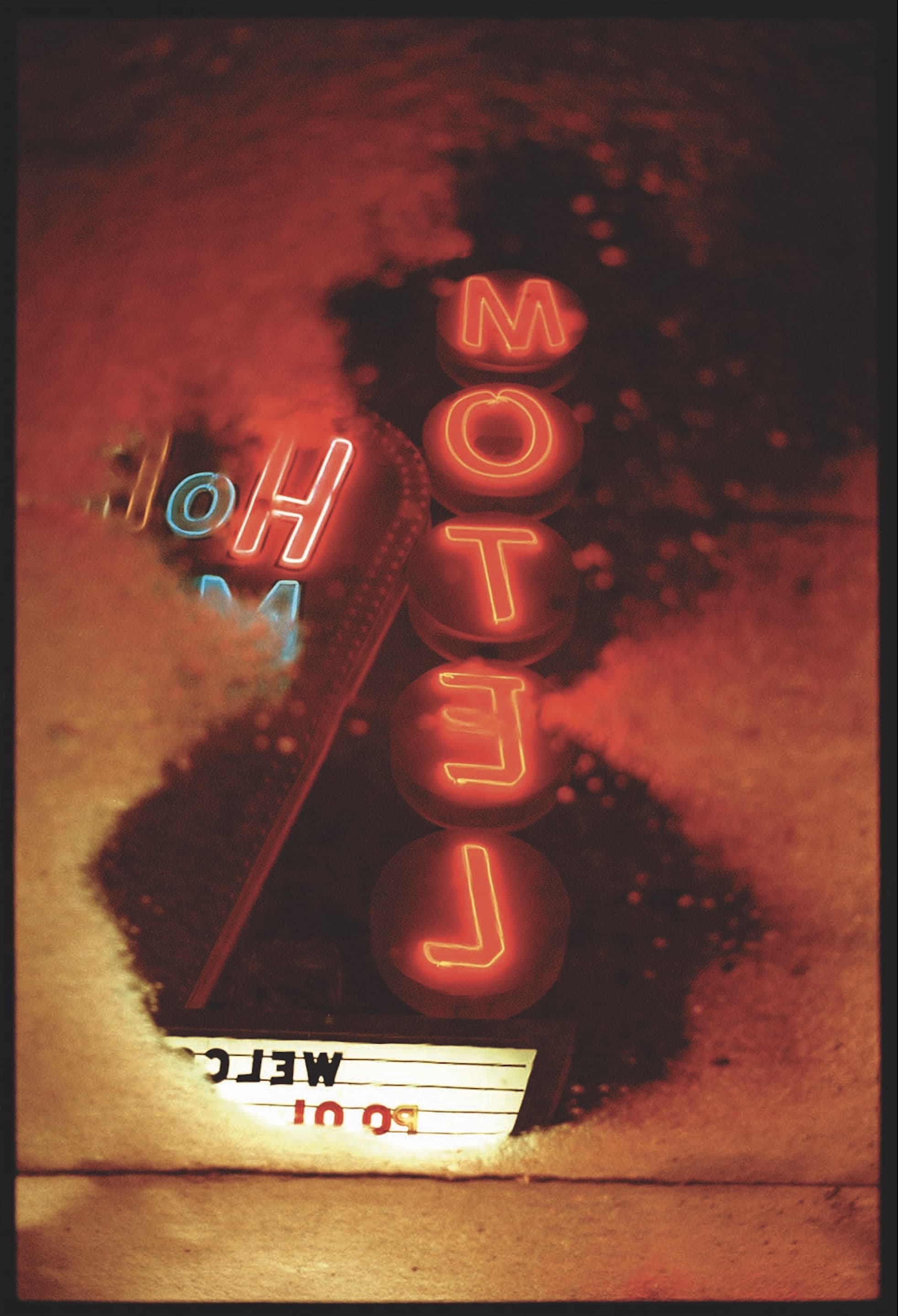

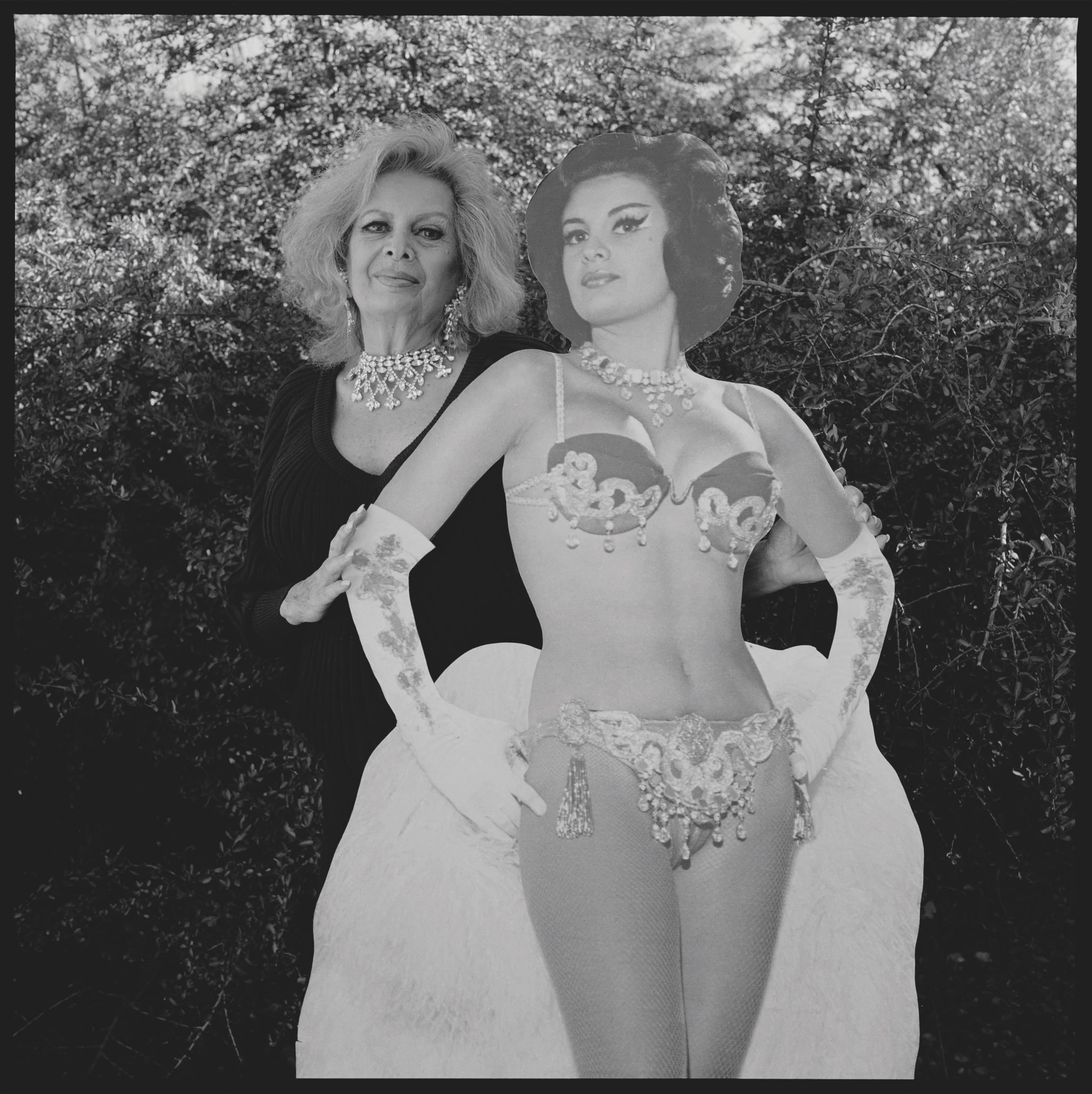

My journey didn’t take me to much of the despair, but it did seem present. I captured some of the decay and broken dreams in the old signs, which felt intense in the colour photography. What I found instead was an opposite side of Vegas that barely exists anymore, and that’s what I wanted to be able to memorialise in my work. I photographed one woman, called Cathy Triffon, who was a showgirl from 1956 to 1981: she took me to her home and she even put one of her old outfits on which still fit her! Showgirls now don’t exist, you’ll only see someone who’s posing outside as a showgirl and you can take your picture with them for five dollars. That era is long gone.

That seems to be the fantasy of Vegas now.

Exactly, that’s why I was so grateful that they could share their time with me and let me document them – this fantasy is fading.

What constitutes fantasy for you?

Just showing the real character, who it really is. You capture the fantasy element, but it’s the reality of what that person truly is that’s captivating.

So for you fantasy is unveiling the reality?

It certainly seems that a lot of the places I’ve travelled to are like that for me. I stayed on a reservation for some time, where we joked about the perception that every Native American you’d see would be adorned in eagle feathers with braided hair. Obviously in reality that’s just for ceremonies, but every day life doesn’t fit the stereotype.

How does it feel to wholly immerse yourself in a community, only to eventually leave it? Do you find it lonely?

No, I think it’s really beautiful to meet all these people. I keep in contact with a lot of the people I’ve met and I try to keep relationships with the people I’ve photographed. It always becomes part of you life and always will be, like with any friend that you meet. I’m always really honoured that they appreciate what I’m doing. The main thing for me is that the people in the photographs are happy with the pictures. If that happens, then all the rest of it just falls into place.

Off the Strip by Hunter Barnes is available worldwide September 2018.