Five photographers reflect on the power of photography

Amalia Ulman

B: 1989 / N: Argentine-Spanish / G: Self-portraiture, installation, digital media

Using her existing Instagram account (@amaliaulman), Amalia Ulman began acting out the tragic story of a fictitious alter ego. Through the images on her feed, we saw Ulman supposedly break up with her boyfriend, move to LA, find a sugar daddy, undergo cosmetic surgery and become suicidal before finding salvation in the arms of a good man. Unaware that this was all an elaborately scripted performance, followers liked and commented on Ulman’s pictures, apparently revelling in her spiralling descent into a state of narcissistic desperation.

Ulman’s work reveals a disturbing truth about how the majority of people use and consume photography. By taking selfies and sharing them online, photography has given us what we all yearn for: an identity. Only, the identity it has given us isn’t ours. To a greater or lesser extent, it is a made-up character, someone we have created to be ‘liked’, envied and, in extreme cases, bought by brands. It means that, as a communication tool, photography is more powerful than ever because it has turned us all into marketers – and the product being sold is ourselves.

Richard Misrach

B: 1949 / N: American / G: Landscape

Beauty and photography have a complicated relationship. There are photographers who are content to make pretty pictures that are appreciated momentarily for their surface beauty. Then there are other photographers, like Richard Misrach, who use beauty to ask more of their audience. Yet this is difficult territory because, if handled wrongly, the seductive look of a work can add a layer of superficiality that dilutes its meaning.

Misrach’s ‘Desert Cantos’ series is undeniably beautiful. His compositions are classic: he photographs when the light is best and his large prints are pin sharp and rich with detail. However, he overlays this aesthetic on subject matter that would typically challenge our notions of beauty. Here we see the wreckage of what looks like an American school bus in a desert landscape. But this isn’t the aftermath of a homeland attack. In a perverse twist, the only aggressor here is the US military, who used this symbol of American values for target practice in the Nevada Desert. For Misrach, the most effective use of beauty is to reflect on ugliness.

Laia Abril

B: 1986 / N: Spanish / G: Fine art

For many photographers, particularly those working commercially, establishing a signature style is vital. It forms their brand and when that brand becomes so recognized, shoots become as much about the photographer as the subject. That, to put it bluntly, is great for business. However, in less commercial areas of photography, such as fine art, some photographers think about style very differently. And for Laia Abril, developing an overt signature style is something she purposefully avoids.

Here are three images from three different series by Abril. We could easily be looking at the work of three photographers: from one series to the next, Abril has adopted an entirely different style. Rather than put her stamp on the work, she is intentionally trying to remove herself. In so doing, her photographic ‘ego’ doesn’t interfere with her intended message. Instead, this helps the viewer to see past the photographer and focus on the work’s thematic concerns. And it’s in Abril’s thematic concerns where she is consistent because, as a whole, her work offers a probing insight into the important issues of female identity, sexuality and misogyny.

Maisie Cousins

B: 1993 / N: British / G: Still life

No matter what she says, Maisie Cousins does take nice pictures – just not the kind your granny might consider to be ‘nice’. This glossily grotesque photograph is both repulsive and intensely seductive. Emerging from the mash-up of shrimp heads, cut flowers and god knows what else is a distinctly girly colour palate. And when accompanied by the series title, ‘What Girls Are Made Of’, it becomes a playfully direct depiction of femininity.

Nice pictures, the kind we see in fashion and lifestyle magazines, are not challenging. They tend to reinforce stereotypes and tell us things we already know; this place is beautiful or that person is pretty. For Cousins, this approach to photography is unhealthily inoffensive and misrepresentative of who or what we are. In particular, her stance against conventional niceness in photography is a rejection of how women have been represented in the past. Rather than aim to idealize individuals for their surface beauty, Cousins reminds us that we are all products of nature. Regardless of looks, you, me and Taylor Swift are just lumps of meat kept alive by an acidic concoction of bodily fluids. If that’s the undeniable truth, then what is the point of taking a nice picture?

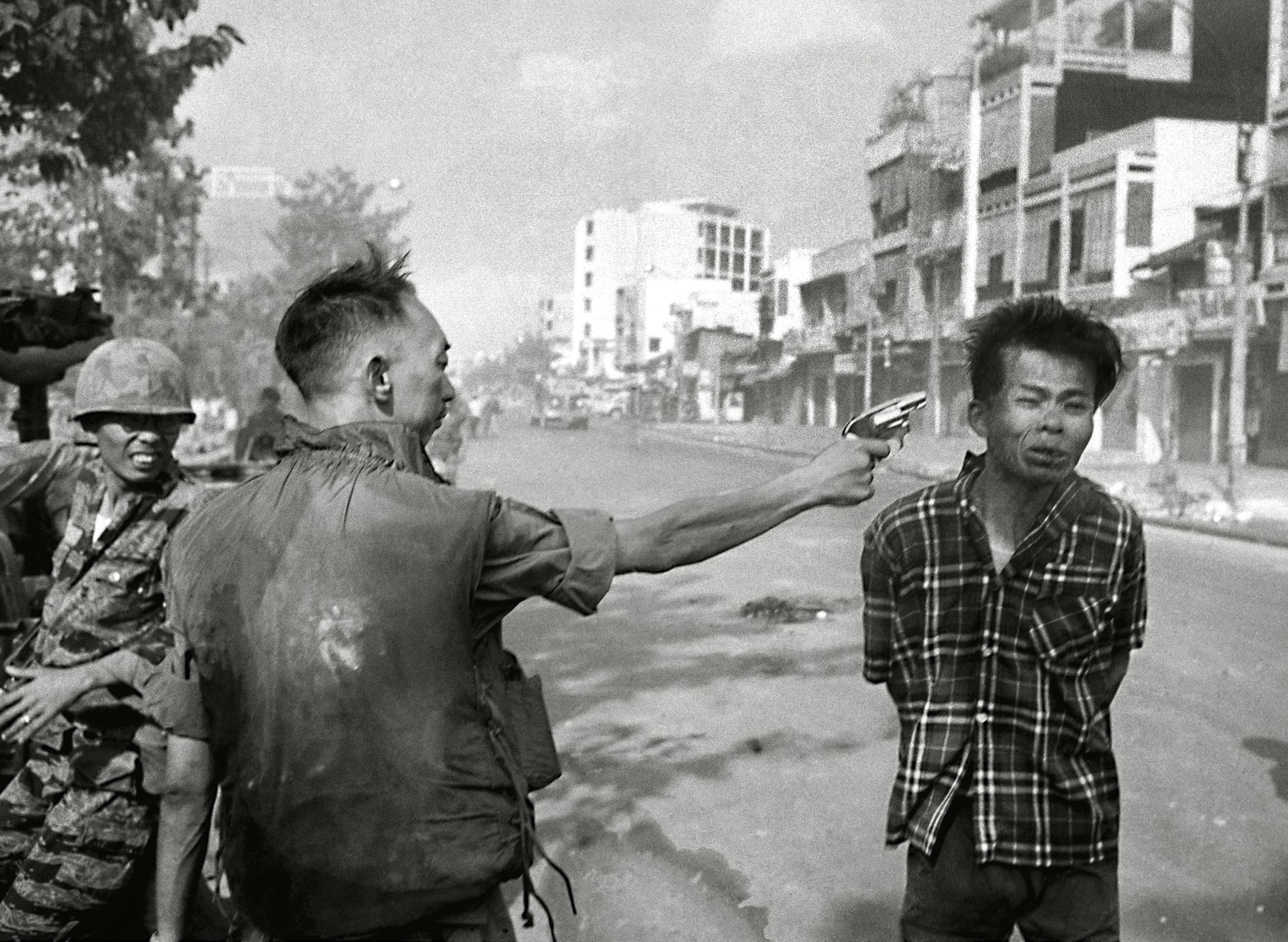

Eddie Adams

B: 1933 / N: American / G: Photojournalism

Captured by Eddie Adams on a humid day in Saigon, this iconic photograph shows General Nguyễn Ngọc Ngạn executing Nguyễn Văn Lém, the leader of a Vietcong terrorist cell. Unaware of what was about to unfold in front of the camera, Adams fired his shutter as the general fired his bullet. Lém died instantly, yet the moment of his execution ricocheted around the world, confronting people with the brutality of war in their homes and around their breakfast tables. It was a photograph that refused to be ignored and one that stirred enough public opinion to help bring an end to the Vietnam War.

Yet what is it about this photograph that makes it so powerful? What quality does it hold that affected so many people? The words used by Adams offer us a clue. He doesn’t just say ‘photographs’, he says ‘still photographs’. We can’t deny that the moment captured is shocking, but it’s the stillness of the photograph itself that makes what we are seeing so incendiary. The photograph insists that we linger on a single, brutal moment. Without sound, without movement, it distils the war into something that slots easily into our consciousness, like a ready-made memory. And once in our minds, there it remains, relentlessly unchanging.

Excerpted from Photographers on Photography by Henry Carroll (laurenceking.com)