How many times do you aimlessly scroll through social media, perhaps fantasising over a life other than your own? How many times do you think, “I want that”, or “I need that”? And when you give in to any of these temptations, does it actually make you feel any better? Momentarily, sure, perhaps it does – but are you really happier? What is enough?

If any of the above sounds like you then you’re an active member of Generation Wealth, and you’re not alone. Over the last few decades capitalism, rampant consumerism and the continuous, exhausting need for more, more, more has been a daily part of our lives, and there doesn’t seem to be any sign of slowing down. Look around, there’s a morally bankrupt tycoon running America, millions of us run up dangerous debt in the insatiable quest for fulfilment, sex, beauty and youth equates to success in women and technology and social media pits us against each other in search of #goals and #bestlife. But how did we get here?

It’s this exact question that filmmaker and photojournalist Lauren Greenfield explores in her profound new documentary, Generation Wealth. Twenty-five years in the making Greenfield, who grew up in Los Angeles and attended a high school frequented by celebrity rich kids, has documented our descent into mass materialism with shocking and often awe-inspiring results – from the parents hiring strippers for their 13-year-old’s Bar Mitzvah to plastic surgery for dogs. It’s no exaggeration to say that Generation Wealth will completely change the way you think about the society that we inhabit, how far you will go to get what you want, and at what cost. Masterfully put together Greenfield speaks to ex-hedge fund managers in exile, porn stars, bankers, celebrity offspring, night club managers and even turns the camera on herself while exploring the links between excess, addiction and insecurity that underpin our hollow society. Profound, probing and necessary, Generation Wealth is the most important documentary you will see all year.

This feels like a very apt time to discuss the idea of excess but you’ve been documenting it for 25 years for this project. What are some of the most sobering changes you’ve witnessed in that time?

Well this project definitely became more profound and urgent for me when Trump was elected. And it was a feeling that I’d had before, at the time of the financial crash in 2008. At first I was documenting the idea of wealth and excess with a critical eye, but not perhaps a full understanding of the consequences and when the financial crash happened it turned it into a morality tale, it was very evidently the price we were paying. And then when Trump was elected it felt like the ultimate expression of generation wealth, or even the pathology of it. He was the apotheosis of it in a way that legitimised my journey.

You don’t always know if you’re on the right track, and if I was attracted to these things that I thought were important but other people wouldn’t. I think there were times in my photographic career where people thought that what I was shooting was marginal or vulgar, part of society that they didn’t want to see. But when Trump was elected it felt like proof that we couldn’t turn away, that this was something that we needed to address. Towards the end of the film there’s a scene where Trump is at a rally and he says, “This isn’t about me, it’s about you,” and that is what I wanted to leave the audience with. He is the expression of what we have become and it has been a long time coming. He is the symptom and we need to look at the disease.

It feels almost like your work was a prophecy.

That was the interesting part about going back and putting the pieces together. An interesting thing happened with that idea and Kim Kardashian, I had been interested and struck by the Kardashain effect on different levels – from the materialism to the sex tape to the idea of ‘keeping up with the Jones’ – this classic American Dream and competition with your neighbour was akin to Keeping up with the Kardashians. When I went back and looked through the pictures it was miraculous – I went through half a million photographs – and when I was looking at the outtakes I found pictures of Kim Kardashian at 12, which I had discarded because she wasn’t interesting then, she was kind of a nobody. But now she has become this touchstone in the culture, and in a way that was the really interesting and profound part about looking back at the culture to see where these things started. I used my pictures as evidence and when doing the film they allowed me to look at it from a more historical context.

Do you feel like the aspirations of wealth and excess are stronger in the US than other placed, is it intertwined with the idea of the American Dream?

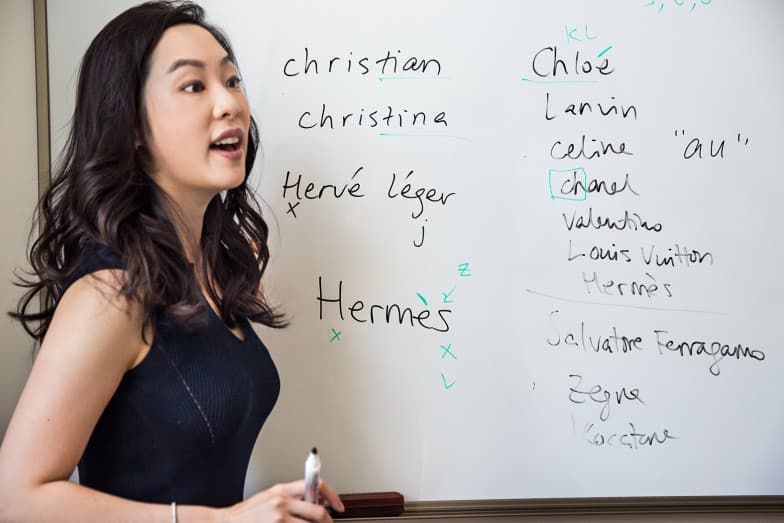

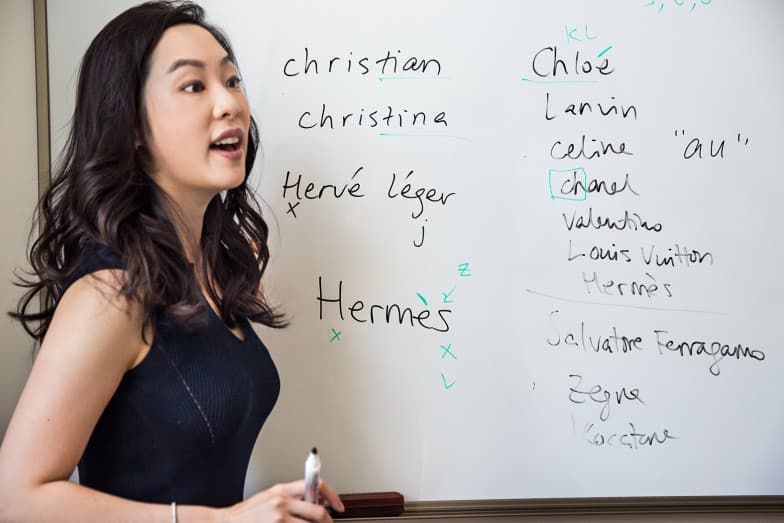

I do think a lot of it does come from the US and the American values, and even in the US I feel like it started in Los Angeles. When I was documenting in the early 90s I felt like LA was a strong part, but of course not the only part. There was Regan and Wall Street then too. But I think that a lot of the drivers – media, globalisation, popular culture and global brands – have made this an international phenomenon.

In my early work I looked at it through the lens of hip-hop and how hip-hop was driving values of materialism among kids from very different backgrounds – rich to poor, inner city to suburban, black, white Latino. But then I would photograph in Italy or Iran and see kids completely covered in hip-hop gear. In the film I tried to show that similar influence when a fisherman in Iceland said that one of the inspirations for how he decorated his home was by watching Keeping Up With the Kardashians. Those influences are not limited by borders. For me, China and Russia were the most powerful examples of that because these were post Communist countries where Communism had tried to level class and inequality and then once they were able to have privitisation and capitalism they had a mad grab for luxury and status in a way that was so visible. That made me realise that where there is pop culture, brands and global media this materialism grows.

You mention Los Angeles being a route cause, but do you feel like the veneer is slipping – from Trump to Weinstein to even the problems with Facebook – has the gloss worn off?

I guess I never really saw it as gloss. I’ve always tried to look at it from both sides where you can see the seduction of it but also the horror and consequence. What I try to do with my work is deconstruct the culture so that you can see the matrix that we’re in, and that gives us some power. I take hope in what has happened with Weinstein and the MeToo movement because, in the film, I ended up feeling like the desire for beauty, youth and sexuality was all an addiction and that the financial crash and personal crashes throughout are the result of not being able to stop. In that addiction analogy the only time you can have a chance for recovery is when you hit rock bottom and so in a way Weinstein makes me feel like that’s rock bottom. We wouldn’t have had MeToo if we didn’t have Weinstein. And maybe we wouldn’t have what’s next if we didn’t have Trump. It’s hard to tell because right now it feels like democracy is crumbling in some way, but I feel like that’s the natural consequences, the underside has to reveal itself for us to move forward.

What really comes through in the film is the idea of insecurity and how that is linked to addiction. How much do you think that people’s insecurity is wrapped up with their aspirations of wanting more? That seemed to be a key trait inherent in a lot of your subjects.

I am so glad you said that, and actually you’re the first person that has picked up on that. I think insecurity is at the centre of this and it’s at the centre of capitalism. If women, for example, are told that their bodies and their clothes are not good enough then they are wonderful consumers, as well as being very vulnerable and chronic consumers. Once they buy that thing that they think is going to fix their problem then there’s another problem, and that’s the way that capitalism works. And while a lot of my work and this film focuses on gender, it’s really about gender as a case study – girls and women as a case study for the exploitation of the human being as the ultimate frontier of capitalism. I think that’s really key. For me it all boils down to insecurity and having a void that we’re seeking to fill with things that can’t fill that hole, so we just keep wanting more.

That is also why I started delving into parenting and the shit that we inherit from our parents that doesn’t leave you and then what we in turn pass on. Everyone tries to do a little bit better than what was given to them but ultimately the baggage is still there and in a way, all of the subjects in the film, including myself, have some kind of trauma or issue from childhood that whatever they’re looking for is seeking to fill.

When do you feel that being rich, or youthful, or beautiful became more aspirational for people than being intelligent or compassionate?

That’s a good question. When I did my book Girl Culture one of the things that I was really interested by was the work of the social historian Joan Jacob Brumberg. She wrote this book called The Body Project in which she analysed girl’s diaries from different periods of time. In it she found that in the 19th century being considered a ‘good girl’ was all about doing good work, doing things for the community or the church. Then in the 20th century, starting around the 50s, being a ‘good girl’ started to mean looking good and making yourself better on the outside. Part of that is the culture of narcissism that has swept in, and in the 25 years that I’ve been working on this project, image has become so important. You can see that in my work in the 90s but then with the internet and social media that has just become so much stronger. I think it’s been a progression. The values of corporate capitalism – which is more about buying and narcissism, image and celebrity – have gotten stronger because the traditional values and institutions have gotten weaker. The influence of the church, secular values and community institutions – whether that be school or girl scouts – provided countervailing values to what we saw in popular culture. The time that we spend with those values has lessened and the time we spend with media has strengthened.

Social media has had a huge part to play in excess, how do you feel that it has exacerbated the problem? And what are some of the differences that you’ve noticed from working in a pre-social media age?

I think that social media has been an accelerant for the primacy of image. Everyone presents with an image these days. And then you use that to make friends, to sell things, grow your brand. Now there is the idea that everyone is the star of their own show, their own personal brand and social media brings that together. It also is an accelerant for insecurity because everyone is constantly comparing themselves to other people, often whose lives are quite fictional. Even the ‘real people’ are fictionalised. We live in an age when you can retouch your child’s school picture, so what used to be a fictionalisation used for celebrities is now little Joe’s school picture.

How dangerous do you think it is for the development of children to live in a society where wealth, sex and beauty are equated with success?

One of the things that struck me along the way is when you ask kids now what they want to be when they grow up, they most often say ‘rich and famous’ which is a dangerous aspiration. I think that staying on that path will only lead to dissatisfaction because as we can see from the film, fulfilment, happiness and satisfaction with life doesn’t come from chasing wealth and excess.

On the other hand, though, the children are the hope in the film, you see people like Mijanou who grew up in a very materialistic world where she felt objectified and yet she has made choices as an adult to unplug from that lifestyle and step away from materialism.

Do you think that the ideas of wealth and sex as currency are skewing what people perceive feminism to be?

I think that’s really complicated. One of the things that I came across in my work with sex workers and people in porn, or even just teenagers posing for social media, is that there is a kind of view that making money from your body, or being empowered to show your body in a way that makes you powerful – through money or fame – is a form of female empowerment. You see that with the strippers, porn stars and even teenagers that feel like if they can own it and use it for themselves then it’s a form of empowerment, but I try to puncture that in this film. For me, Casey Jordan – the woman who went on the bender with Charlie Sheen – is trying to puncture that narrative and show that there is a consequence for not just the women involved, but really for all of us as we become dehumanised in the exploitation of our bodies in whatever form that takes. That can be the little girl in a princess pageant that is seemingly innocuous or selling your body for money as a prostitute. I think that this idea of empowerment is a distortion of feminism, a myth. It’s a generational peak, this idea that as long as you’re using your own body then it’s a feminist expression, but I don’t agree with that.

What emotions did you experience towards your subjects? Was it empathy, pity or more of a judgement was about the culture that they inhabited?

Definitely the latter. I try to be really non-judgmental in my work, particularly because a lot of it is human nature and many of us in their situations might respond similarly. I’m indebted to people who open up their lives to me and make themselves vulnerable to allow us to see the matrix. Often they are the ones who are the most critical themselves – like Adam in the film who is at his own Bar Mitzvah and says that “money ruins kids”. The people in the eye of the storm are the ones that can offer the wise words. I do feel a lot of empathy too and that’s really why I ended up putting myself in the film. I have learned from this journey and these subjects and I hope that that is what the audience takes away. Sometimes a photograph can feel very ‘other’, very voyeuristic and that’s why I wanted to do a film, it has the ability to get you emotionally involved.

Was there a side of you that didn’t want to put your life, and your children on show?

In the beginning I was not planning on being in the film with my family. It ran counter to my instincts as a photojournalist and I had never done it before. But when I was starting to put together this film I realised that my journey had to be the connective tissue between all of these very different subjects. Even then I didn’t want it to be personal, that part just evolved as I was making it, the same way that my interviews evolved. What bubbled up was this niggling thing that I was hearing from Florian (the hedge fund manager) about the cost of his work on his family and when he said “how could a 100 hour work week not effect your family life”, and that hit home. At that stage I’d been on the road for two weeks and was on my way to Iceland to do more filming. I had been connecting with my kids through FaceTime but I couldn’t help to see some parallels that caused me to consider my own passion for work as an addiction. I was completely consumed by the project and that made me question why I’ve been following this for 25 years, and what drives me. As I was going deeper into the subjects lives to figure out what was driving them it felt natural to also look at myself. My work depends on people being honest and vulnerable and I realised that I needed to be willing to let the camera be turned on myself too.

Generation Wealth has been 25 years in the making, and the idea and study of Generation Wealth is definitely not over in a societal sense, but is it over for you as a project?

I feel like the Generation Wealth project is over for me. I put everything into it and left nothing unturned. It took 30 months to edit, the book is 500 pages long, getting the movie out was the last piece of the puzzle. I gave it everything and it was definitely cathartic so I feel like this chapter is now finished. The photographic chapter has changed now too. A lot of this work was driven by magazines and by print and that source of inspiration is not the same any more. So in this form it is done but on the other hand one project has always lead to the next and I’m sure that whatever I do next will have it roots, somehow, in this work.

Generation Wealth is in cinemas nationwide from today, distributed by DogWoof