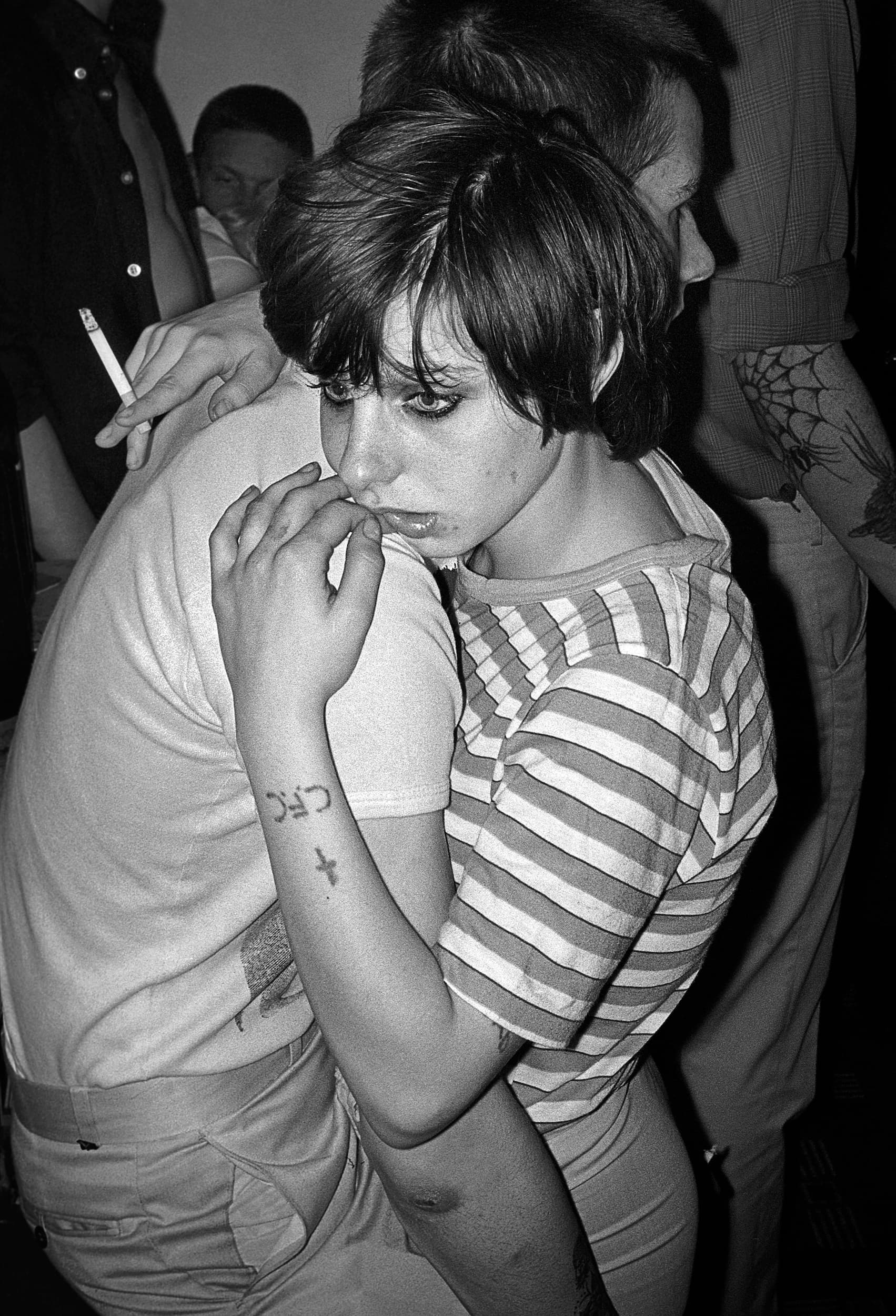

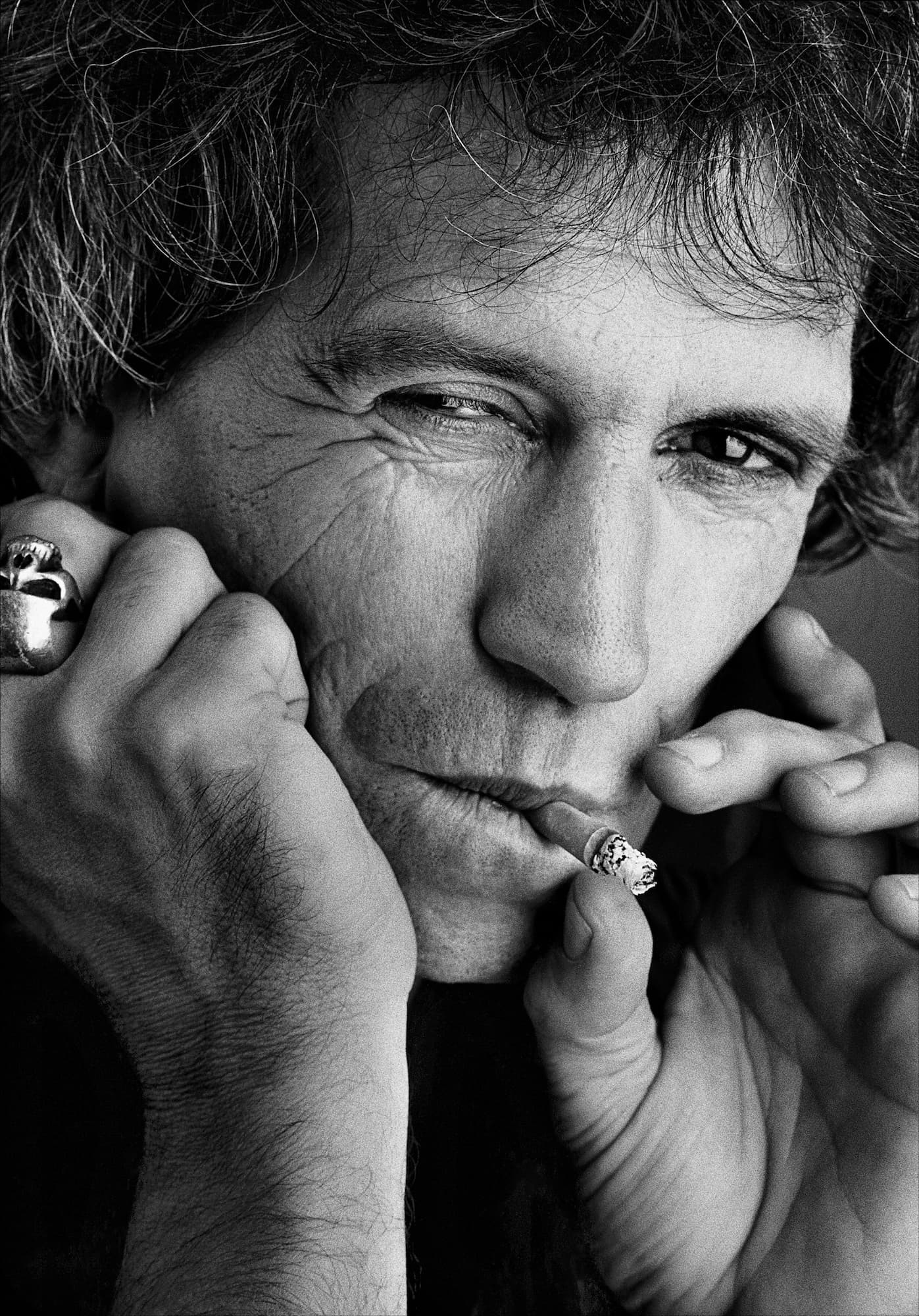

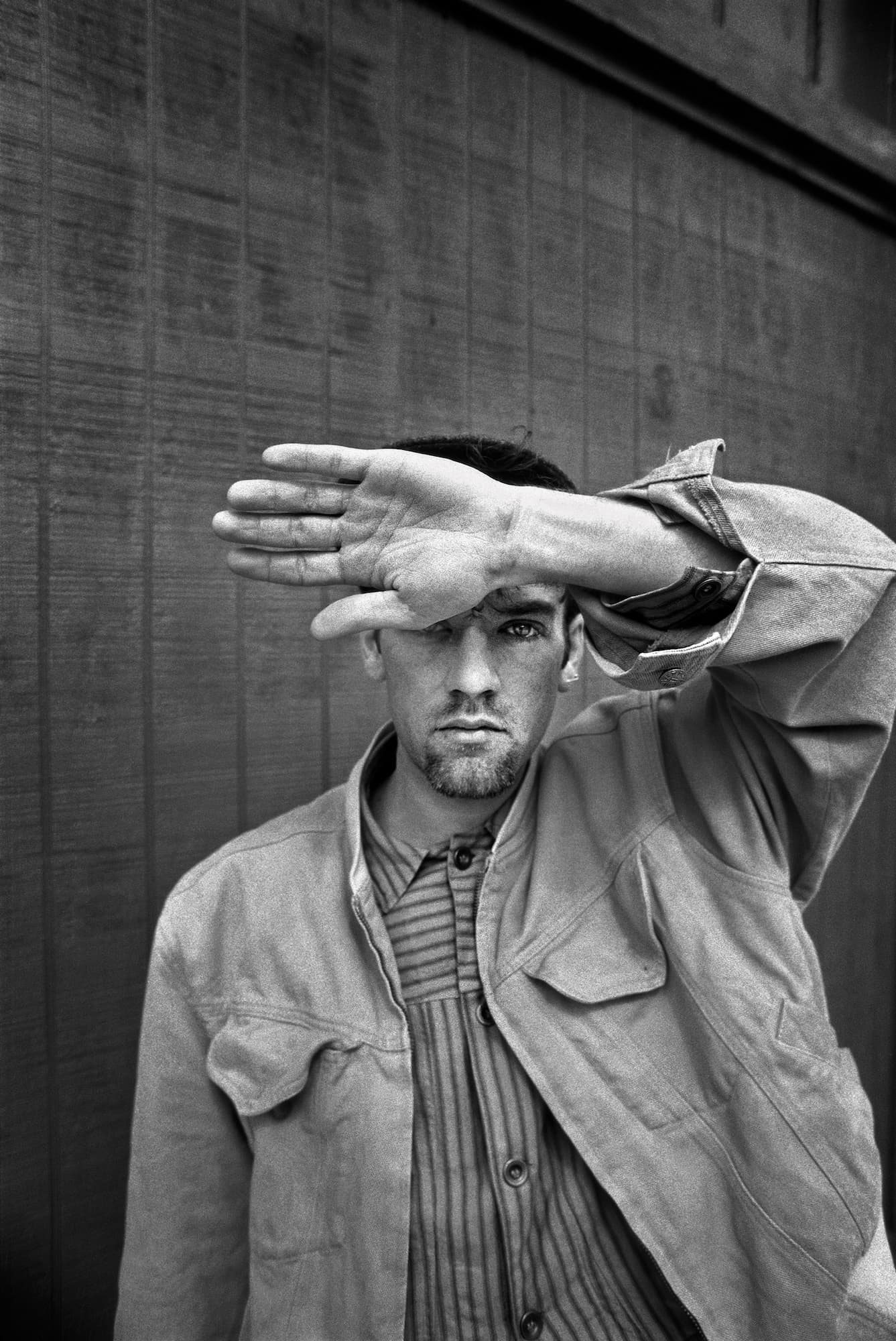

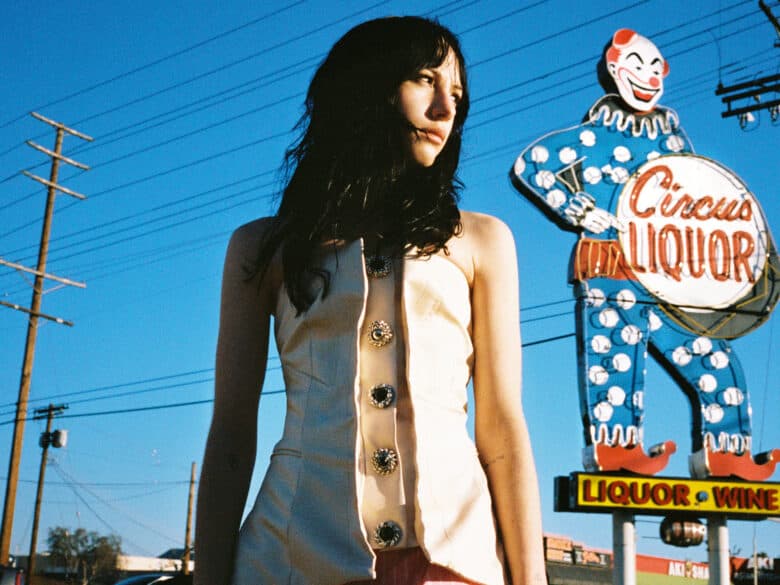

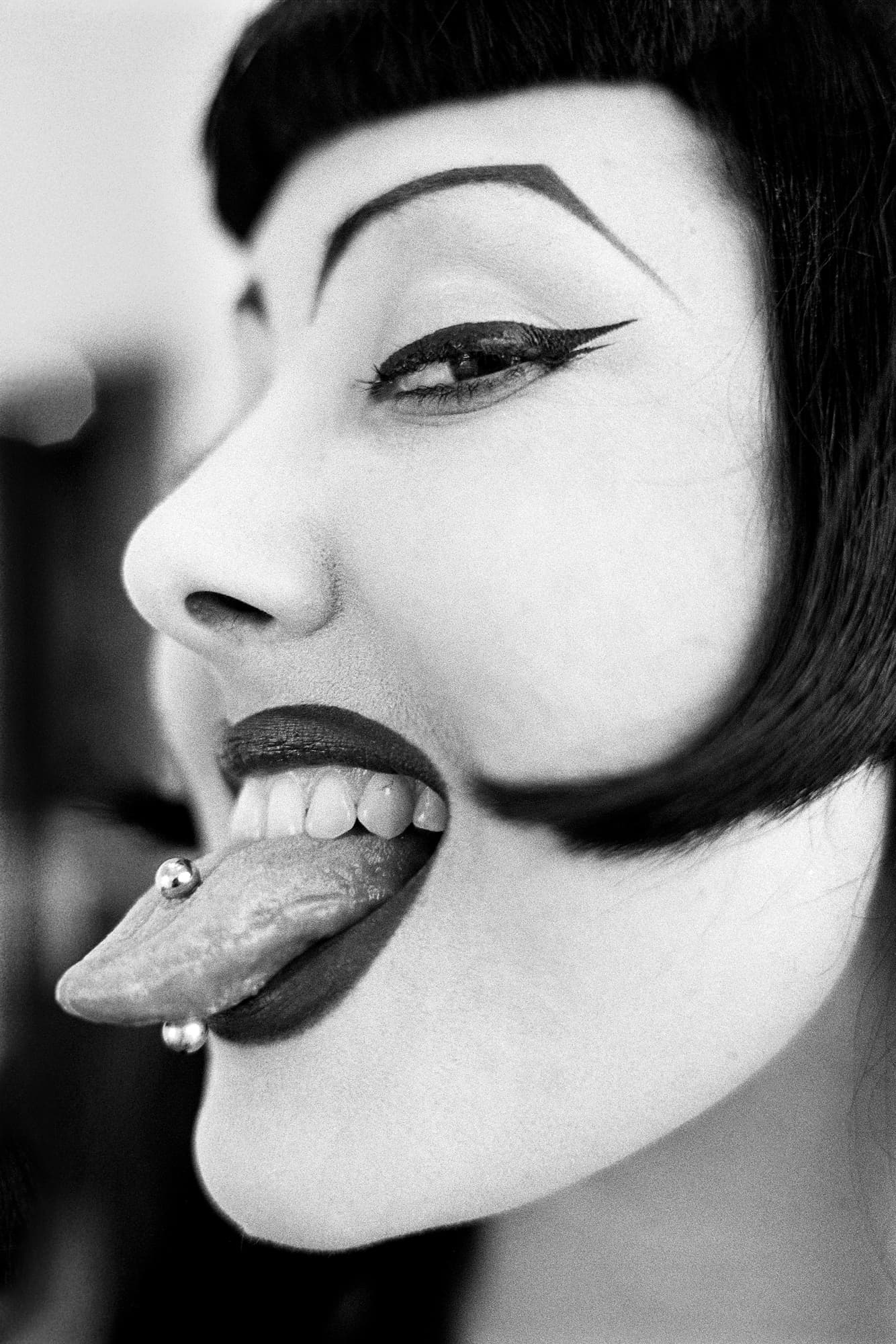

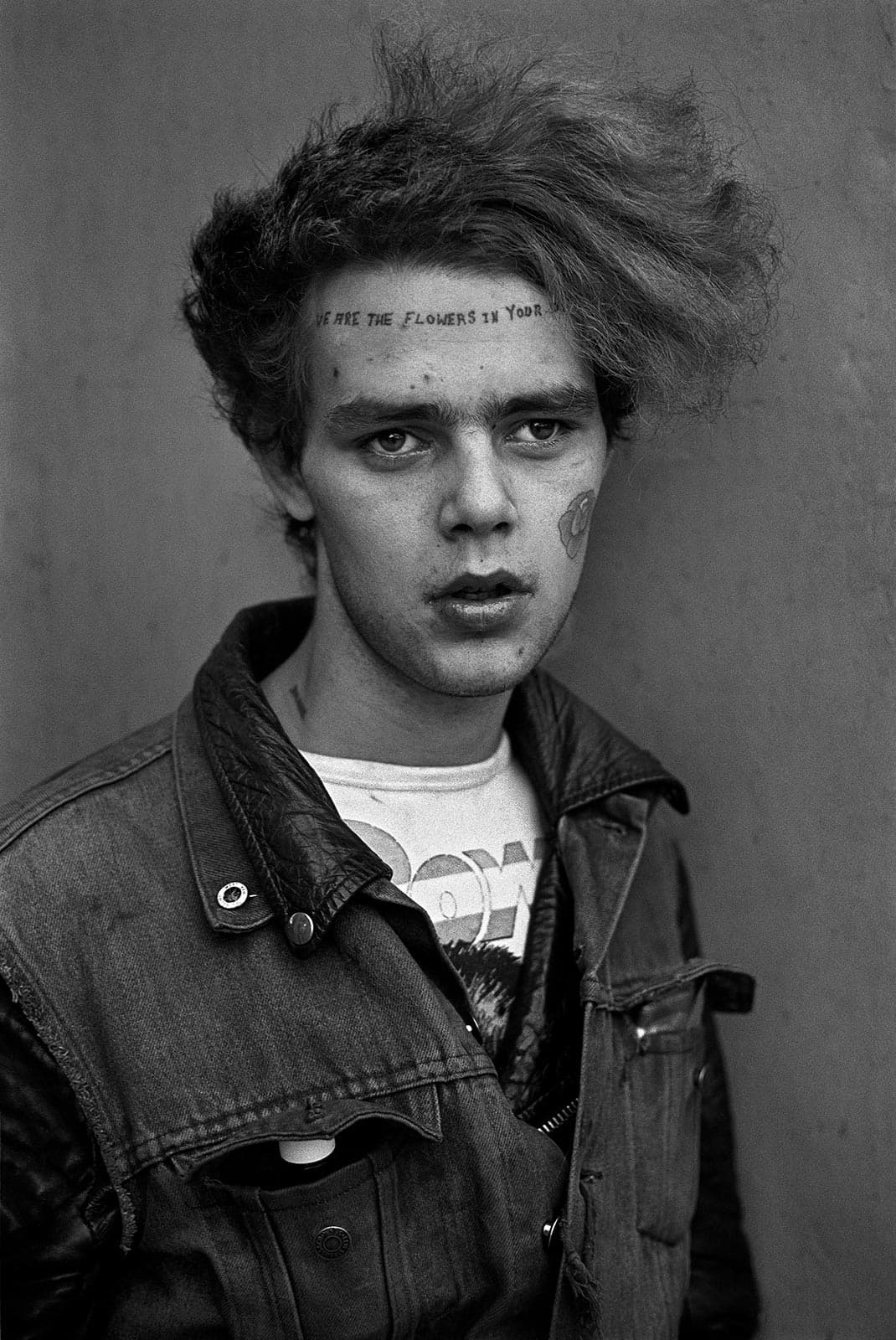

Get to know seminal subcultural photographer Derek Ridgers

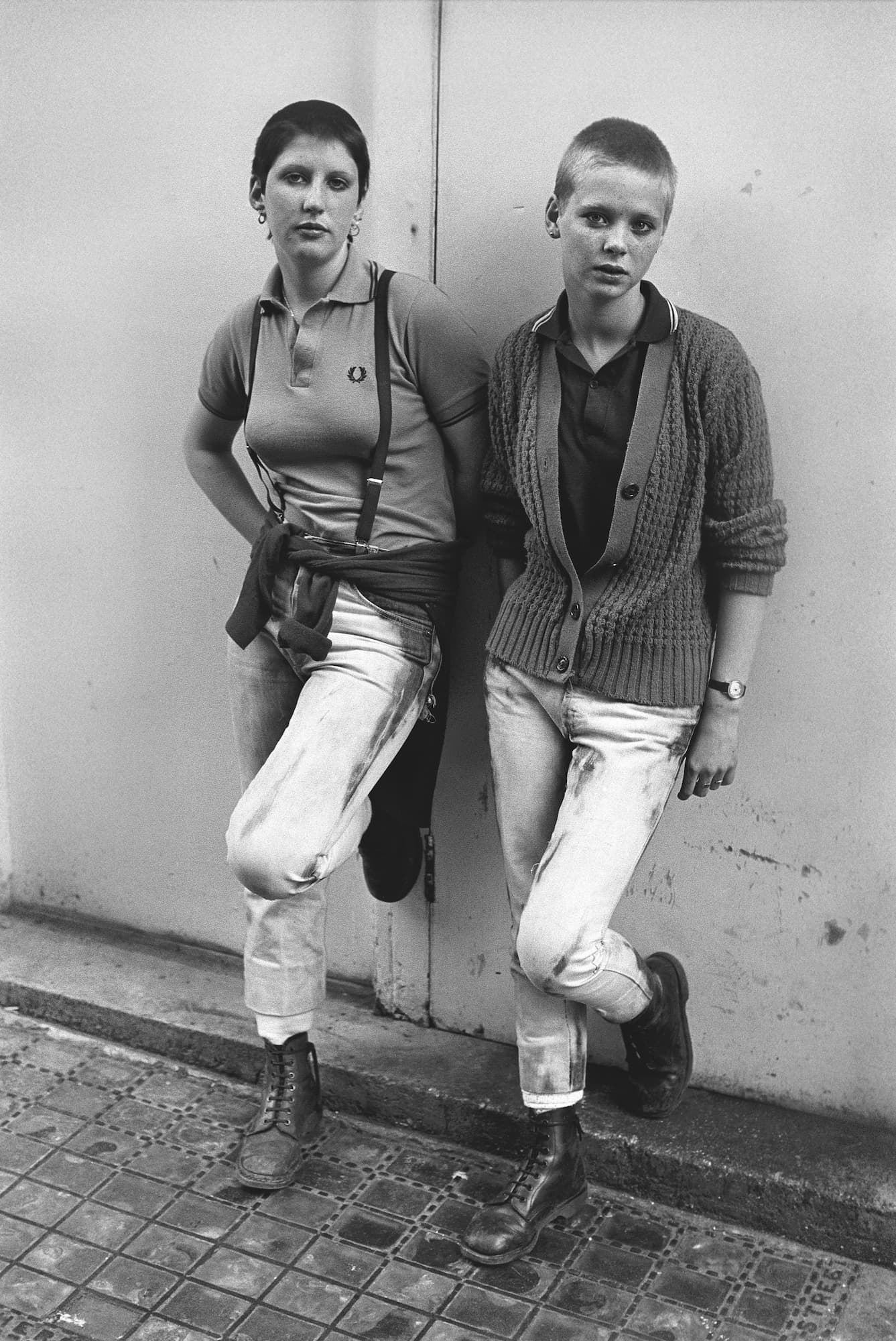

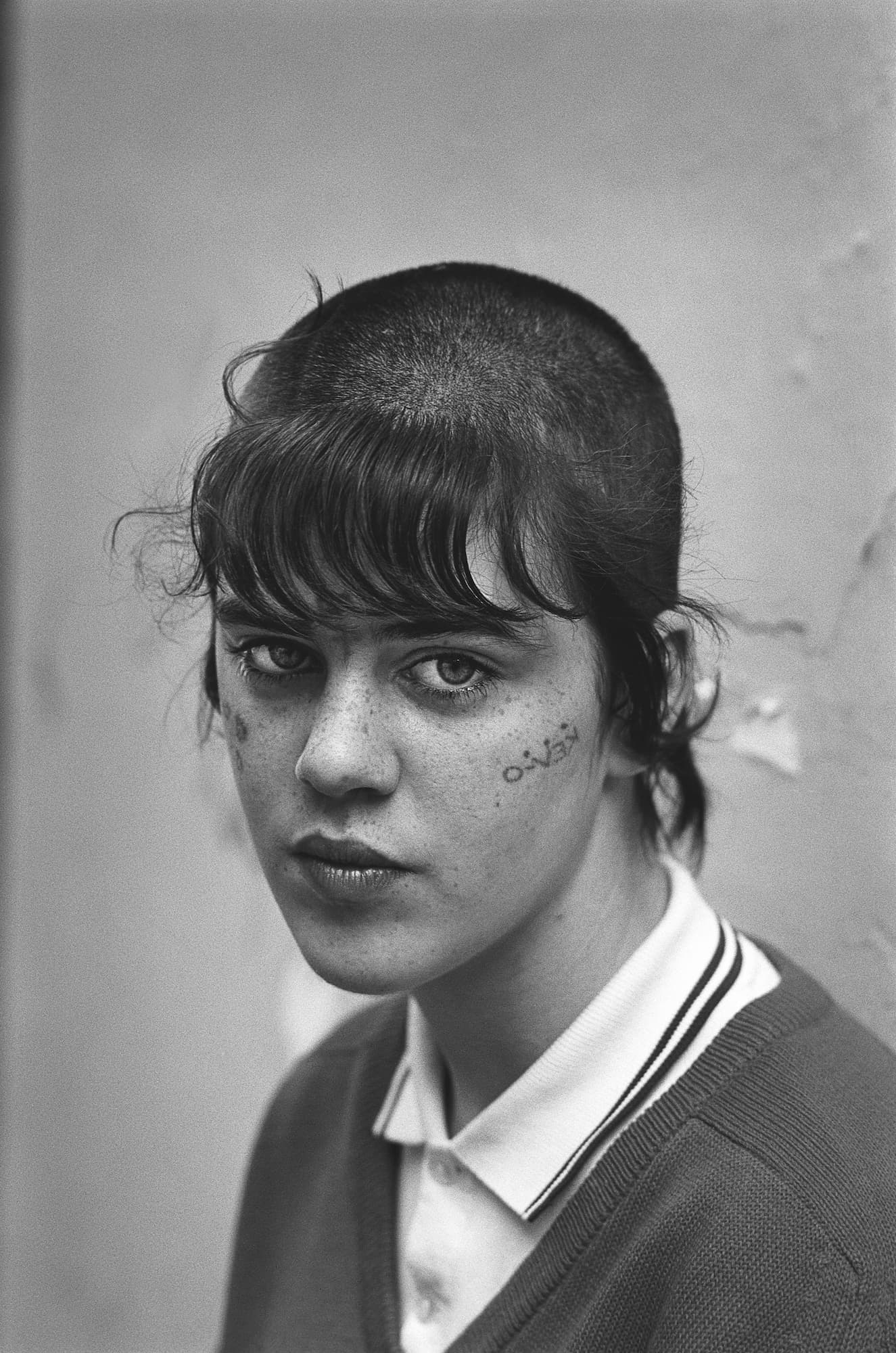

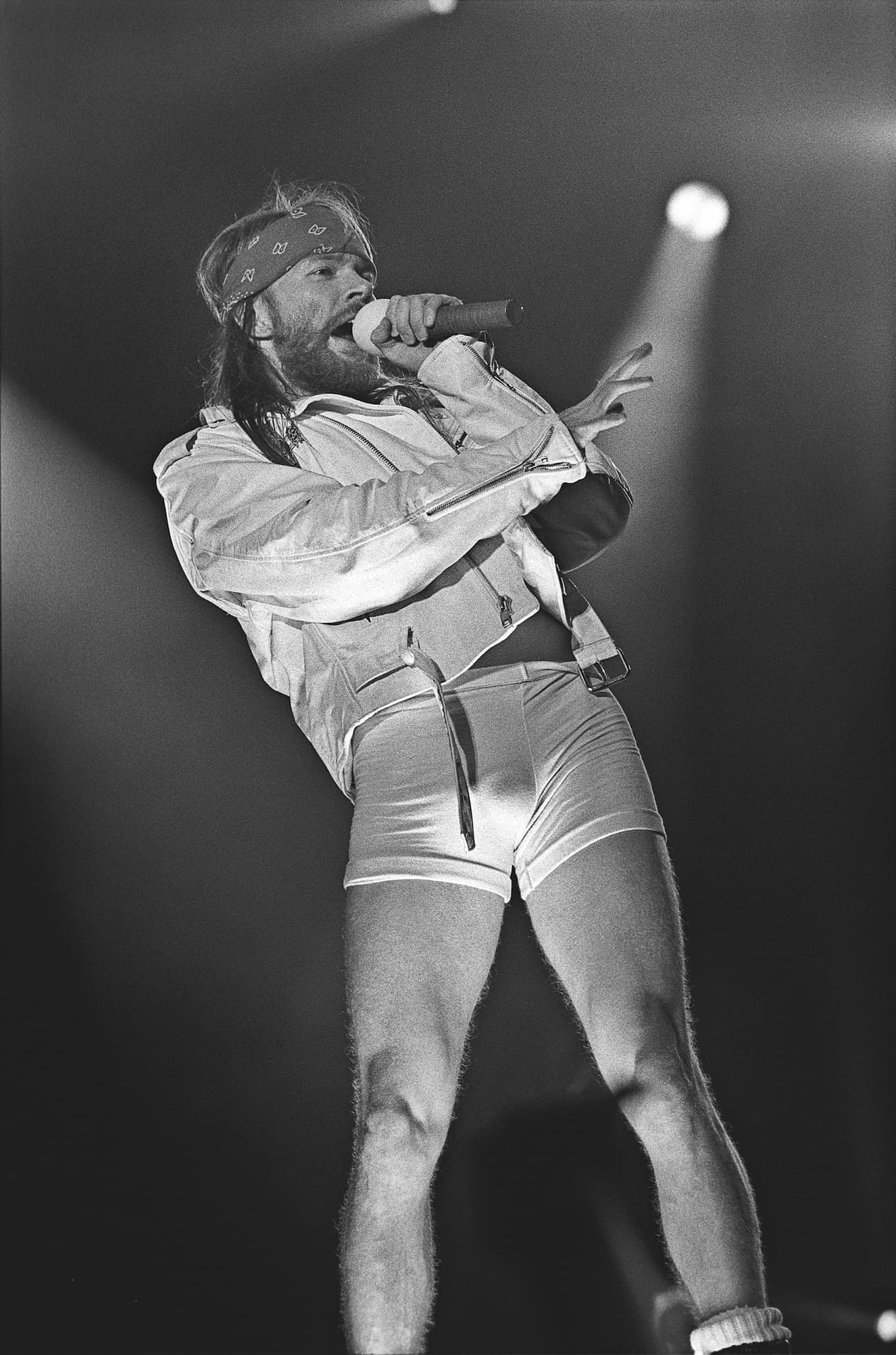

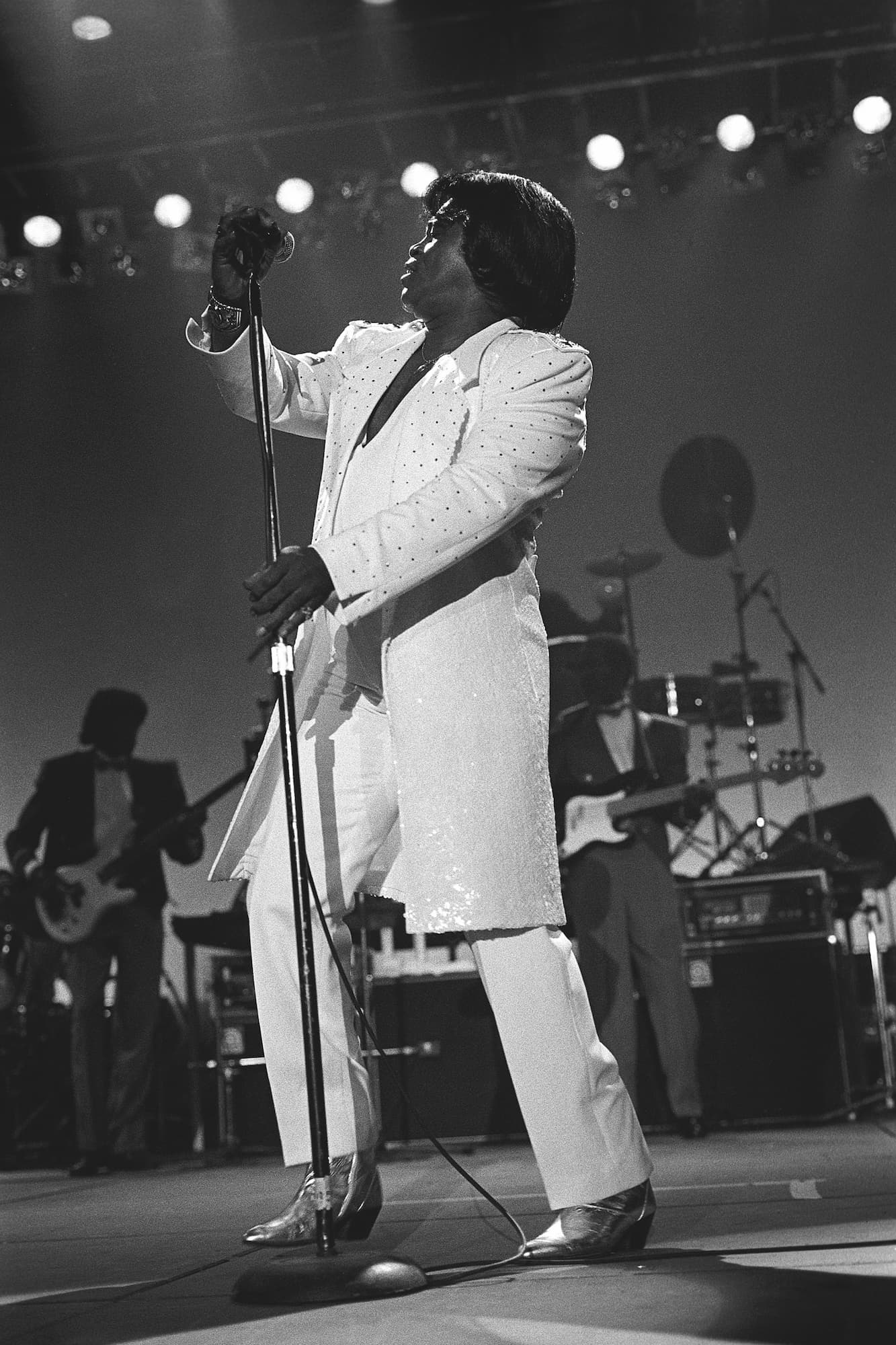

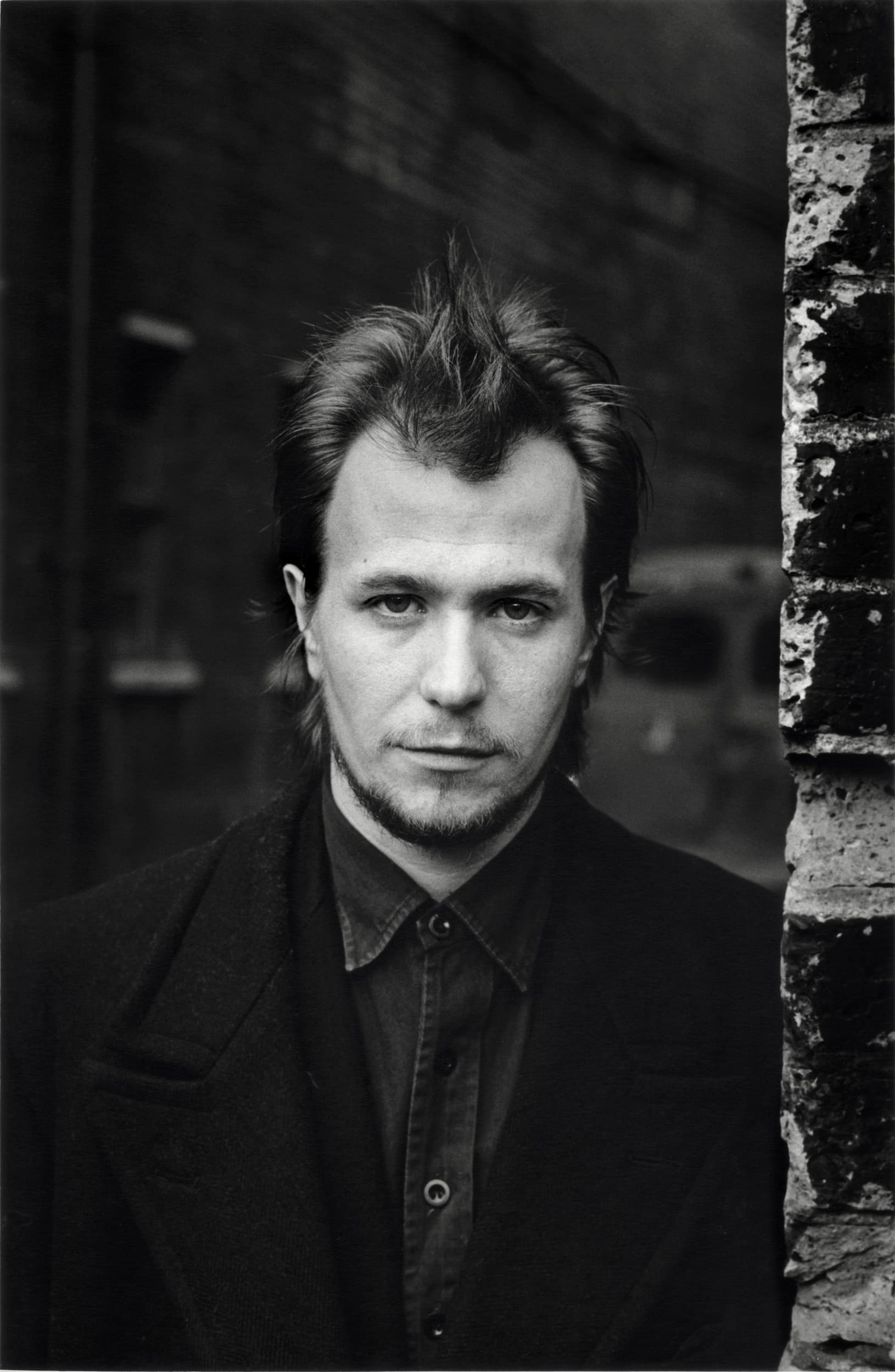

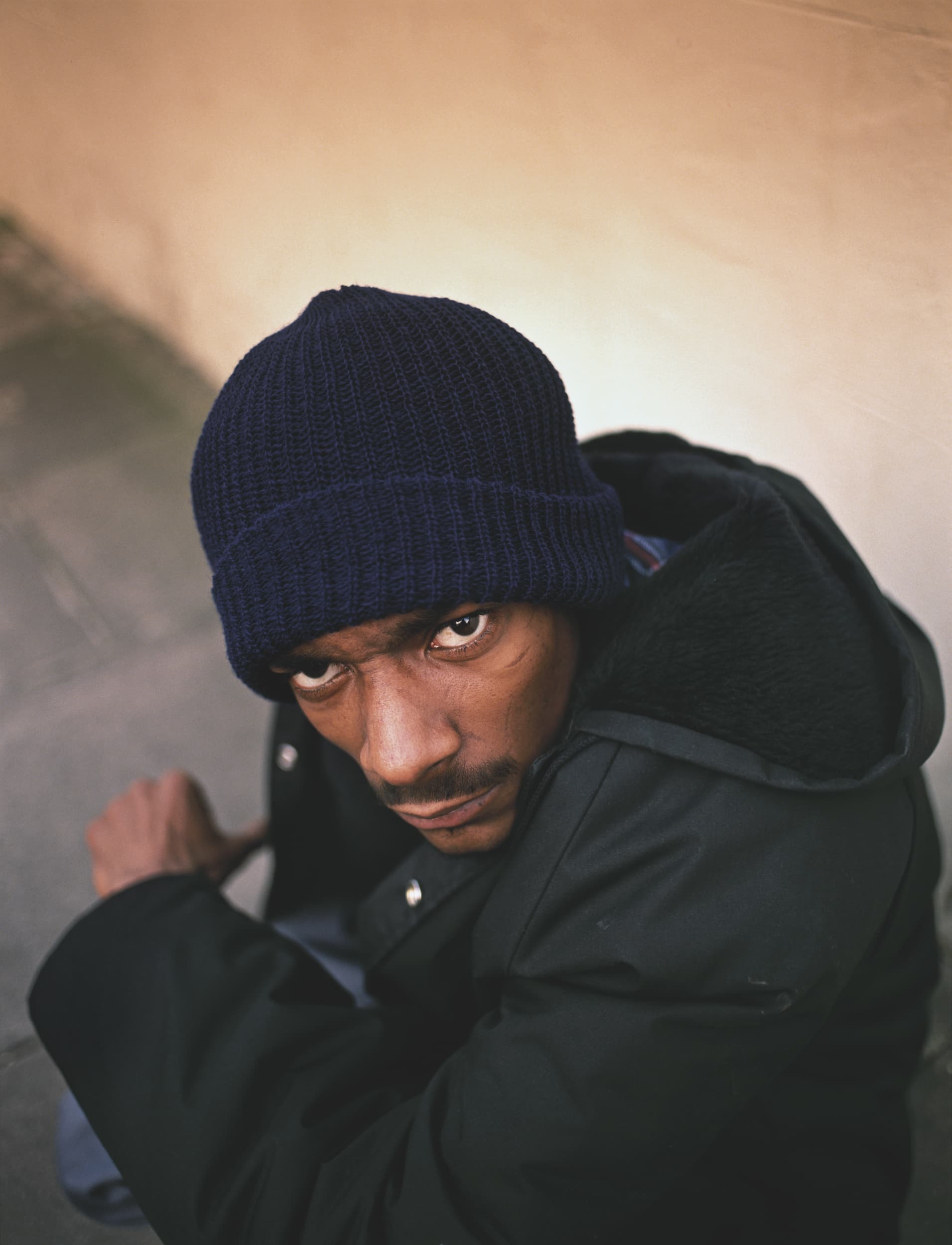

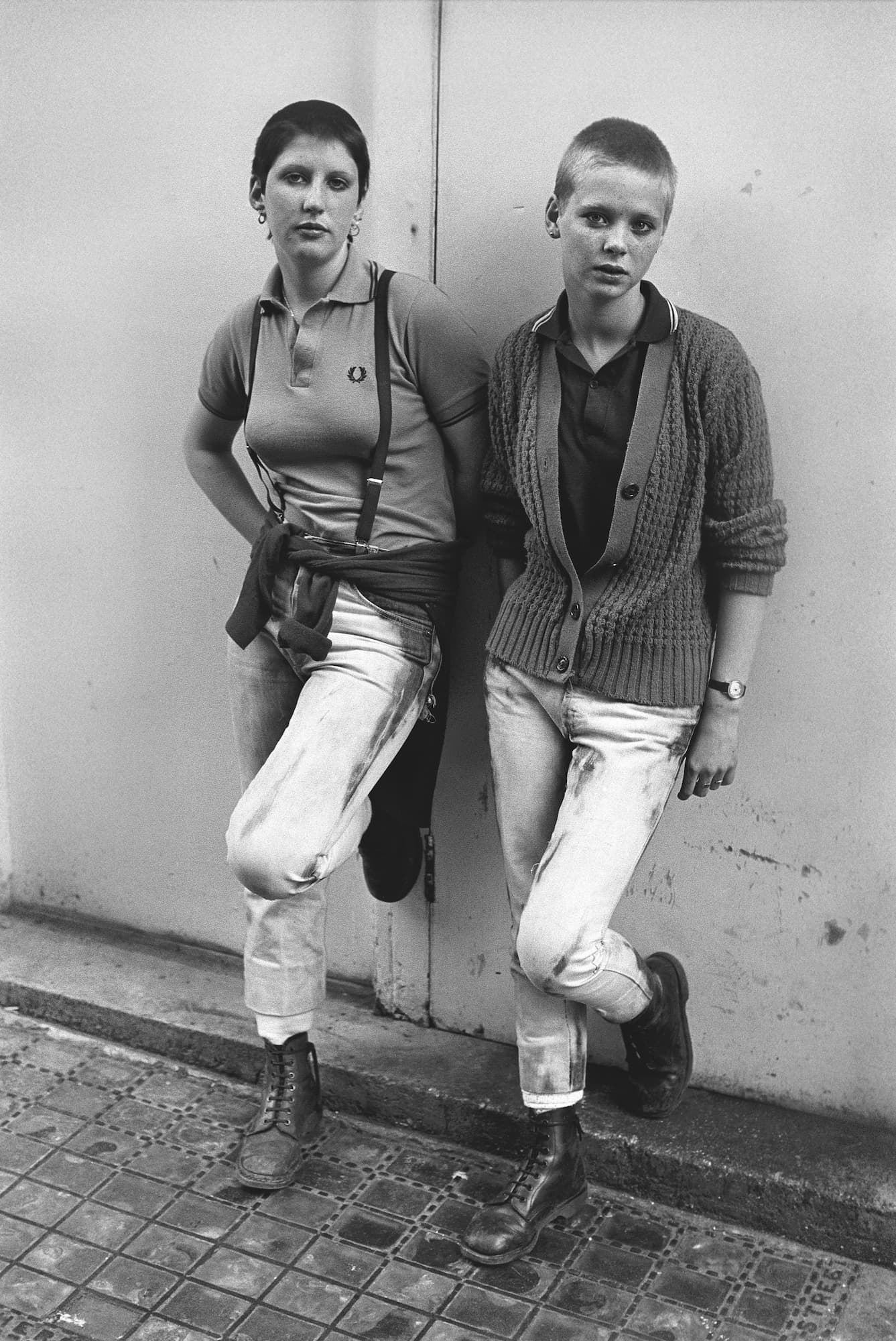

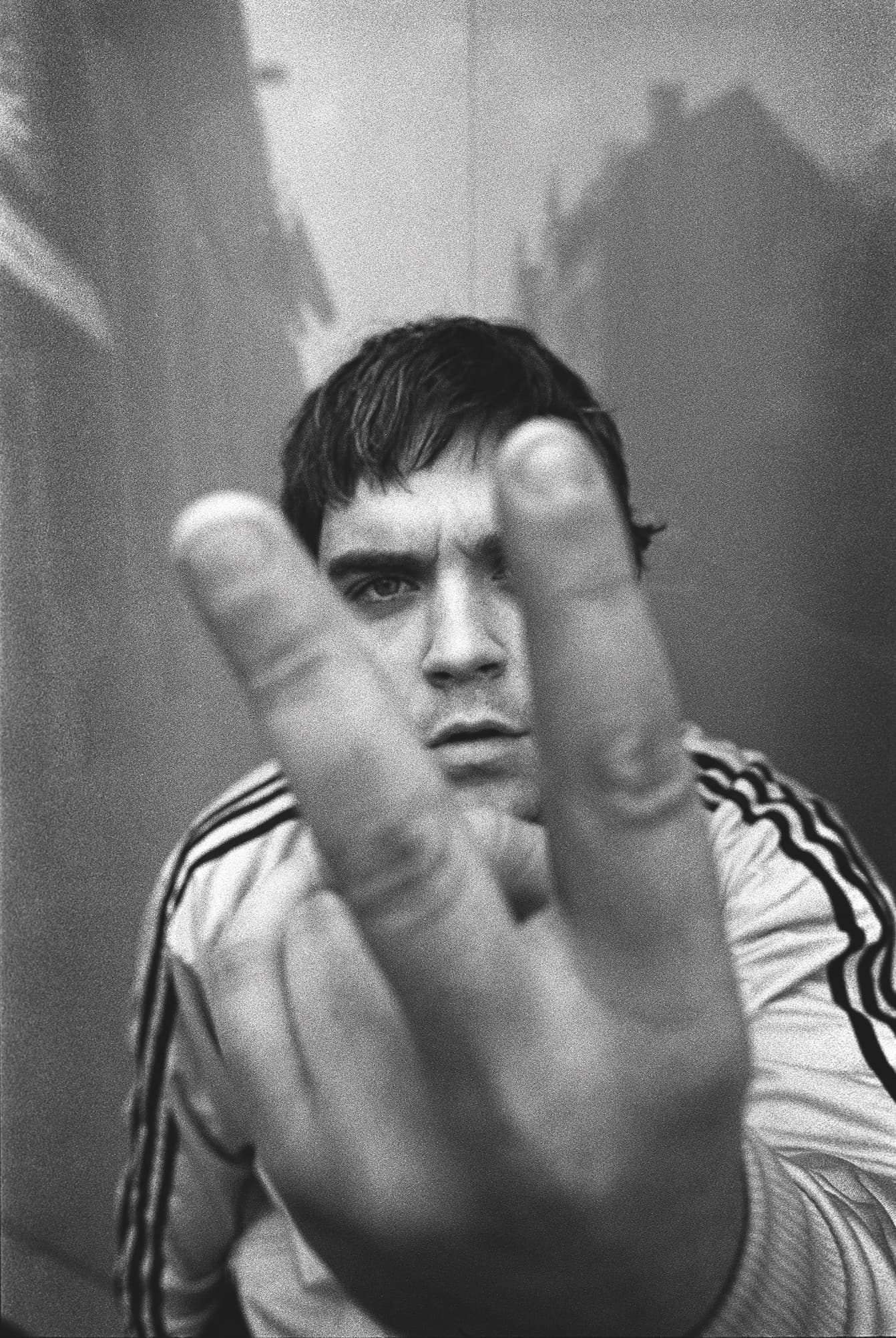

London born and bred, Derek Ridgers has lived through six decades and captured as much as he can. With a career spanning over thirty years, both he and his photography have stayed as powerful and relevant since the day he started out. Shooting the likes of Tim Roth to Snoop Dogg, Kylie to James Brown, as well as encapsulating subcultures of punks and skinheads, Ridgers’ work is a timeline of London culture and a captivating history lesson. We caught up with the photographer to find out about his newest project with ARTBLOCK, a book and exhibition curated by Faye Dowling, and to get to grips with his photographic life.

Do you remember the moment you fell in love with photography?

Yes. It was a warm night in the summer of 1986. I was at the Rencontres d’Arles photography festival in the South of France. Some of my early rock photography had been chosen to be shown in the Roman Amphitheatre, up on a big screen, alongside work from Baron Wolman, Elliott Landy, Jim Marshall, Anton Corbijn and many of the other great rock photographers of the previous 25 years. People were queueing up, all dressed up to the nines and the whole place was packed. I thought I’d arrived. Of course, it didn’t quite work out like that. But from that moment on, I actually felt that I could say that I was “a photographer.” And I got the distinct impression that that my life might be different from how it had been before.

What does photography mean to you?

Photography has given me a fantastic life although, I admit, I’ve been very lucky. I’ve worked for myself now for nearly 40 years and it has never been boring. I’m my own boss and I don’t have to commute to go to work in an office (although, to be honest, I quite enjoyed that life too). I’ve been all over the world, almost always at other people’s expense and stayed in some of the world great hotels. I’ve met a lot of my heroes in music, film and literature and even, occasionally, gone out drinking with them afterwards. My new book is my tenth and, although I may take a bit of a break now for a few weeks, I have no intention of stopping. I have several projects that I think would make decent books and that deserve to be seen. Honestly, what’s not to like?

Who or what has been your greatest influence over your career?

The truth is rather prosaic. I suppose it was my parents. They were the biggest influence on me because they were such unusually unsociable people that they made me a little bit that way too. I was an only child and we were a very small family. As a kid, I spent a lot of time in the company of my grand mother. Just us two. I went to art school at the age of 16 and at that point I was really very immature. I grew up quite quickly but my maturity was a long time coming. I’m still not too sure if it’s arrived yet. I suppose I should also mention my art teacher at Spring Grove Central, in Isleworth; Mr Edwards. I came back to school after taking my ‘O’ levels and I thought I was going to be in the sixth form for a further year to do my ‘A’s. The tutors had other ideas and it was clear that they’d be happier if I left school. Mr Edwards found me a last minute placement at Ealing School of Art, due to someone else dropping out. I don’t even think he asked me about it first. I was in the sixth form on the Friday and an art student the following Monday. My life would have been very different it it hadn’t of been for the last minute intervention of Mr Edwards.

Your work captures cultural eras and subcultures so well, in what ways have you seen your work change through these?

I don’t think my work has changed much. I found a very straight forward, easy technique and basically stuck with it throughout. I have a real respect for the photographic process and I think it has a vérité quality without much real intervention from from the user. I try to keep myself of the equation. I see myself more as a ringmaster. Or someone wandering around with an empty picture frame and occasionally asking passers by to look through it.

Do you think there are still subcultural movements today as significant as the ones you’ve experienced over the past few decades?

I suppose the key word in this question is “significant”. I’m not sure those subcultural movements were seen as significant at the time but only perhaps looking backwards. And maybe the photographs of people like me make it all seem more significant than it really was? But these same sorts of young people are all still around today. There’s probably more of them but they are more spread out. When punk first started in London in 1976 there were probably only a handful. And they got photographed over and over again. We even know most of their names. By the end of that year, when the punk club The Roxy opened in Covent Garden, there might have been a hundred in the whole country. Nowadays there’s probably more than a hundred punks in every big city in the world.

How do you feel technology has changed photography? Do you think it’s had a positive or negative effect on the arts in general?

Overwhelming positive. If the Nikon D850 had been around when I started out as a photographer, I reckon my work would have been 100% better. But then again, so would everyone else’s. And I could never become a photographer nowadays because what I once saw as being my USPs – curiosity and persistence – would have much less traction now. Everyone has a camera these days and so they don’t need people like me in order to get themselves seen. That’s what Instagram is for. Digital imagery has been great for photography but not always great for photographers. Or rather, those who see themselves as ‘professional’ photographers. Photography forums all over the place are awash with old and bitter photographers who feel that all the young upstarts have come along and taken their jobs away with iPhones. The reaction of the photographic community to Brooklyn Beckham’s first book was a case in point. In my opinion, some of the work in it was more than a bit ropey (I blame the publisher there) but some of it was really rather good and IMHO he’s a massive talent. But he has a famous name so the keyboard warriors came out in force. Back when I started, professional photographers would build a carapace of mystique around themselves. I worked with many like that as an art director. But the truth is, photography isn’t even a profession in the real sense of the word. Anyone can just pick up a camera and call themselves a photographer. I did exactly that myself.

If you could photograph just one thing for the rest of your life what would it be?

People. Ideally, one person. I love the idea of one photographer, one subject, one camera and one lens and just making it up as you go along. If the subject is interesting enough in themselves and an icon of popular culture to boot – like Marilyn Monroe or Frank Sinatra, or beautiful enough like Christy Turlington – you’d have a job for life.

How do you recall your photographic memories?

I used to tell the stories surrounding some of my photographs on my, now long dead, blog but I stopped because it occurred to me that I should aim to have my photographs to tell their own stories. And if they can’t or don’t, then they are simply not good enough photographs. In fact, in some cases, explaining a photograph can weaken it considerably. I think I sent you a couple of photographs from the series I did about when porn stars meet their fans? I feel those photographs are so very odd that they are stronger being left totally unexplained.

If you had to choose just one photograph for people to remember you by, which would you choose?

I suppose my best known photograph is Tuinol Barry. The image that was on the front of my best known book 78 – 87. When she was alive my mother said his face was very much like mine. I can’t quite see it myself but coming from my own mother, it must be right. But it’s really not up to me to choose anyway is it? These things are decided, or not, by the World.

What five films have shaped you the most?

To be honest, I’m not really sure I’ve been “shaped” as such by any film. My selection isn’t very cool… I’m not much of a film buff and generally hate most modern films. These days, I’d far rather read a book. I was an 11 year old schoolboy when I first saw It’s a Mad Mad Mad Mad World. I loved the bit with the girl dancing in the bikini so much I sat all the way through just to see that bit again. I saw From Russia With Love with my parents in the local Odeon about a year later and loved that film too. It seemed to speak of a completely different world to all the dull little lives we lived in Heston in the early sixties. Peter Watkins TV film Culloden was on TV around that time and, although I think I only ever saw it once, it was an incredibly powerful work which I’ve never forgotten. I guess I also saw Blow -Up whilst I was still at school but my parents would never have taken me to see something like that. I probably went with a few mates. I always found it to be a rather boring and unresolved story but the fabulous life of Thomas the photographer, with his topless Rolls and bottomless models, seemed totally captivating. Maybe that film shaped me in some way? It was still seven or eight years before I picked up a camera myself but something must have stuck. And what baby boomer does not love Woodstock? I saw some of it again recently, in the round at the V&A, and it’s still an extremely impressive document of the time. I’ve always considered myself a bit of an old hippy and I can honestly say that I saw most of those bands live too. It brings back many memories.

What’s next for you?

I’m working on a photozine with the artist @ratteface and also a couple of books for 2019. One will be an unauthorised one about Nick Cave. A bit of a departure for me because, unlike my recent books, I’m not designing this one myself. Other than that, I have new career as a fashion photographer. This isn’t because I know about fashion or even want to know. I’m not a fashionista and much of it, I find appalling. At fashion industry events, I feel as much an outsider as I did when I was photographing skinheads or punks. More so, if anything. But fashion photography is an excuse for me to continue to take photographs of beautiful people. I suppose that’s all photography ever was for me really. Just an excuse.

Derek Ridgers book and exhibition (curated by Faye Dowling) is in association with ARTBLOCK at the Old Truman Brewery, London from 4-7 Oct