Grimes on how she created her character-led interactive alt-pop

The following feature is taken from Issue 4 of HUNGER.

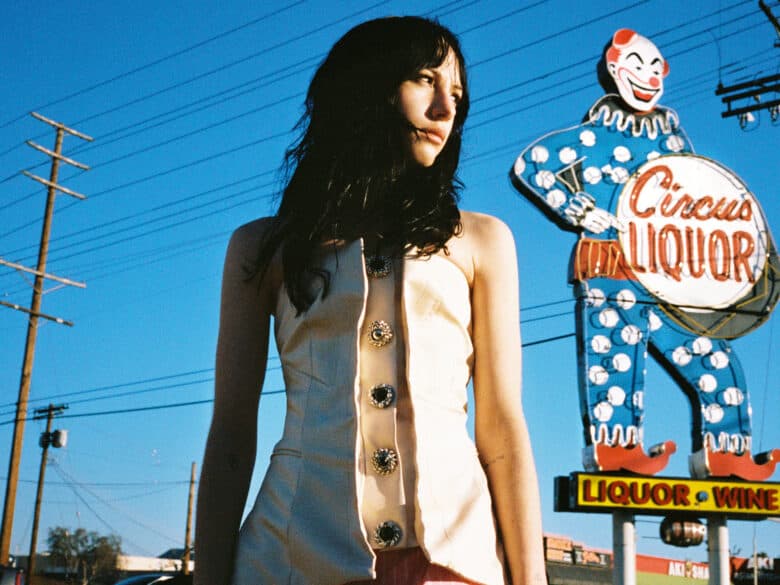

The future is now; the perfect, hybridised music icon of tomorrow has been discovered. She was born, allegedly, Claire Boucher in 1988, in Western Canada, however, she is best known as Grimes: the mysterious alias for her artistic exploits. It’s claimed that Grimes is human, but she is also known to possess superpowers – powers that convey a higher-level of being or an elevated form of technology or, perhaps, both. Yet even the highest priest of cybernetic knowledge could not have predicted the multimedia majesty that is Grimes.

“I’ve done things other people haven’t. I’ve engineered a pop star but I just used myself as the subject – if that makes sense.”

What is known about her is this: Grimes’ album, Visions, proved a surprising highlight in a desperate musical landscape in the year 2012. Visions provided a vivid model of next-level songwriting and production: at once perfect in all its digital glory, yet frayed at the seams in an evocative, provocative manner – as if a computer code designed to create the idealised pop star was defiled by a hacker with an artistic bent, and a flair for the fantastical.

“It’s the antithesis of being authentic. But it is authentic because it’s my passion.”

As such, Grimes appears to have been created from various obscure strands and ruins of pop culture. Indeed, she is the complete package: producer, songwriter, performer and video director – a visual and conceptual artist as much as she is a harvester of melody and song craft, an auteur of sound and vision. Perhaps the most original thing about Grimes is the way she embraces unoriginality. She is obsessed with references. She’s blissfully postmodern, unrepentantly aware that her persona is a steampunk construction of various influences patched together.

If you haven’t figured it out by now, Grimes has, at the ripe age of 24, become the ultimate pop artist. Visions self-consciously teems with yesterday’s sound of tomorrow and tomorrow’s fantasies of nostalgia. There’s synth-pop redolent of the 80s, created by someone born in the twilight of that decade; hip-hop beats deracinated from their R&B roots; lush, stacked voices (all Boucher’s) resembling a medieval choir, yet placed against a space-age backdrop, the ethereal “New Age” atmosphere retrofitted for the dystopian dread of now. The sound of Visions is simultaneously inviting yet confrontational, bold but willfully vague and hazy, and colourised but not colourful (and that’s a compliment). The contradictions suck you in, compelling, even as they confuse and seduce.

“With Visions I started to embrace the idea of pop not just as a sonic thing but an interactive thing.”

Amidst the robotic beats, an organic feminism emerges. “I didn’t experience a lot of sexism until I entered the music industry,” she notes. “It was a difficult thing to buy a microphone because the guy at the store wouldn’t take me seriously.” Grimes’ womanhood remains at the fore of what she does: take the time when, instead of the traditional t-shirt as concert merchandise, she and an artist friend created surrealist “pussy rings”. “It was like an idea from Cronenberg or David Lynch – confronting someone with the biological reality of the vagina but removing it from the human body,” she says. “I love confounding the archetype.” Boucher/Grimes is also quick to pay homage to the female iconoclasts who paved the way to where she is today. “I’m super inspired by Lisa Gerrard and Liz Fraser as vocalists and songwriters,” she notes. “When I discovered Karen O at the age of 15, it was one of the first times I realised women had a place in experimental music – this was before I found out about Siouxsie and the Banshees, Lydia Lunch and that whole lineage.”

“Taylor Swift is a genius: the key similarity between us is that she has so much control over her career. She feels really new, and is a kind of power.”

As much as Grimes reveres her maverick elders, she also finds solace and shared mission in her peers, who hail indiscriminately from the pop and indie arenas. “Among my contemporaries there are some really awesome women, like Julia Holter,” she says. “Raphaelle Standell-Preston, the singer in Blue Hawaii and Braids, is an unbelievable songwriter and vocalist; she taught me how to sing in a lot of ways. Lana Del Rey is really cool, and a lot deeper than people think. M.I.A.’s ability to construct her mythology is a talent on its own; I like Azealia Banks and Rihanna, too. Azealia is a world-class performer – I love how she operates in both the mainstream and indie spheres, I’d love to produce her.” Grimes’ primary obsession currently, however, remains Taylor Swift, whose combined stature and independence she respects. “Taylor Swift has sole songwriting credit on most of her album and it’s really good,” Boucher/Grimes gushes. “She’s a huge icon of mine, even though the artistic sphere in which I operate is anti-Taylor Swift.”

“I like looking at the worst things – things I’m not supposed to touch – and figuring out what’s good about them, like Nickelback. Not that anyone can find anything good about Nickelback…”

Grimes knows what she’s doing when she claims to love Taylor Swift; she knows it’s a provocation against indie orthodoxy – the very crucible in which her persona was created. As a student at Montreal’s McGill University, Boucher became involved in the city’s pan-artistic, avant-garde loft scene. In that context, the most extreme move proved the most accessible, “I started making pop music in the first place because I came up in the noise-music world where everyone was making really aggressive, atonal sounds,” she says. “It was funny to do pop music and that’s what got me started. Doing the opposite of what I was supposed to do, playing with the sonics that Taylor Swift uses – certain kinds of vocal and guitar things specific to country music. For me, it’s a radical thing. Max Martin [the songsmith behind hits for everyone from Katy Perry to Britney Spears] is my idol. I want to be like him when I grow up!”

“I don’t like the distinction between ‘high’ and ‘low’ art; terms like ‘indie’ and ‘mainstream’ don’t mean anything. People consider Justin Bieber lowbrow but he has the highest-end producers; then you see major-label artists like Sky Ferreira tapping into the indie market, and people like Skrillex and Arcade Fire breaking into the mainstream.”

This is a classic pop-art stance: once the most shocking of possibilities can be readily accessed everywhere, then the only thing left is pushing beyond the canon of good taste. “Enya gets a bad rep because she’s, like, music your parents listened to, but she’s inspiring to me,” Grimes/Boucher claims. “She was cool especially because she had so much input in her production and the recording process, as well as for her incorporation of ancient Celtic things. I like using the sonics of medieval chorale, but putting it into a pop context – that’s something people haven’t really heard.” For Grimes, listening to “Stupid Hoe” by Nicki Minaj is a contemporary equivalent to the shock that audiences felt when they first heard Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring”. “The degree to which they upset people is interesting in itself,” she says. “They’re both so awesome – atonal and all over the place, and disturbingly sexual. I love the idea that a piece of music or art could be so crazy it causes a riot.”

“Social media was the means by which my career was even able to happen. You don’t need to be on a major label to break.”

According to Grimes/Boucher, she first became known by sending her early recordings – Geidi Primes and Halfaxa (both 2010) – via email to tastemaker blogs like Stereogum, Pitchfork and Gorilla Vs. Bear. “I came up at a time when the music industry machine was falling apart – and it’s still resolving the crisis of downloading and torrents,” she explains. “It was a kind of crazy free for all: you didn’t need a publicist to get into Pitchfork.” In the process, Grimes built her audience outside of the traditional label system: she now has well over 80,000 Twitter followers, a number that grows daily. “I like to troll them and write things that I know will upset them,” she laughs. “Twitter is interesting, you can test out ideas and see how people respond. If I tweet about Game of Thrones, I’ll get 700 responses; then I’ll write about an important scientific innovation and get, like, two. Sometimes fans get very personal, sometimes they get weird; I’ve gotten to know some and talk to them often. My favourite fans are the Mexican emo-Goth teenagers – they’re the least creepy and most fun.”

Grimes can’t remember a time when she didn’t interact with a computer, she even spent some time as a hacker but “despite some minor victories, most of my hacking was done alongside people much better at hacking than me.” As such, she credits the diversity of sounds on the Internet as being the spark that makes her music, and that of her peers, so exciting. Early in her career, she coined a term for what she does – “post-Internet” – and then regretted it instantly. “I like the idea of coining a term but I said it in passing,” she says. “It’s technically not the best term for what I was trying to describe: there’s a neurobiological difference in people who grew up with the Internet because of the neural pathways they formed at the age when they were developing. If you were on the Internet at that age, you had access to infinite knowledge, so what does that do to your brain? People my age were the first people who grew up with this infinite access, so there’s been a huge explosion in the last few years in terms of the diversity of music net. Having access to Napster at a very young age, during the period of my life when I was cementing my musical taste, meant that I was listening to Ligeti and OutKast and Marilyn Manson. That’s why we have all these insane hybrids: it’s a product of people who grew up listening to everything.”

“I was actually way more interested in astrophysics than neuroscience but I wasn’t good enough at math. Even with neuroscience, I cheated my way through and I lied to get into the program I was in.”

“People assume that I’m an airhead, a druggie,” Grimes/Boucher groans. In truth, she may be one of the most intellectual pop stars you might stumble across. When asked what piece of outmoded technology she’d like to be reincarnated as, Grimes/Boucher responds without hesitation, as if the answer to such an absurd question was already imprinted on the circuitry of her motherboard: “Deeper Blue – the computer that beat Gary Kasparov at chess. It’s one of the few non-human things to get close to simulating the responses of the human brain.” Before she was kicked out for cutting too many classes to, say, go on tour with Lykke Li, Grimes studied neuroscience at Montreal’s prestigious McGill University. “Neuroscience and astrophysics had the same appeal as music: they’re all trying to understand what humanity is, addressing the question, ‘Who are we, and where do we come from?’” she says. “At the end of the day, how does a neural impulse turn into an enjoyable experience? No one knows. Studying neuroscience, you come across these massive mysteries whereas art seems insanely logical and well constructed.” Likewise, she remains fairly irate that critics miss her “many awesome literary references, like Darkbloom [the title of her 2011 split album with d’Eon], which comes from Nabokov and [song title] “Oblivion”, which is a David Foster Wallace reference. It’s a huge part of my creative process. I’m probably as inspired by literature and film as I am by music. The most emotional experiences of my life have been literary ones, from discovering Lord of the Rings to reading The Idiot by Dostoyevsky, which was one of the most intense; I always think about that when I’m making art.”

“I want to build a sustainable career. I want to do this for the rest of my life.”

Boucher/Grimes considers her ultimate idol, however, to be the multi-talented medieval Christian visionary Hildegard von Bingen: “I want to be her – she was the first Madonna. She convinced everyone that she was a prophet and genius. She ended up running her own abbey, and wrote medical books about abortion, as well as being an amazing painter and composer. She spent 16 years in a cloister – when she left, she was my age. With Visions, I tried to do a lot of the things she’d done: I locked myself in a cloister, fasted, and engaged the spiritual side of myself, which I hadn’t done in a long time. I tend to like music that’s dissociative, not super-engaging with the real world.” In the flesh, up close, Grimes/Boucher exudes a startling, powerful charisma: her face is an unlikely vortex that pulls the eyes, the lens, the camera, whatever, to it; the steady, sure pace of her voice is a calm, siren-like draw. If anything, she recalls Yoko Ono’s combination of Dada mystic and avant-garde allure, mixed with the irresistibly toxic DNA of a plastic-fantastic pop star a la Britney. You might break up The Beatles for this woman, when, in fact, she might actually be The Beatles. Just don’t call her cute. “It’s the bane of my existence, that I’m considered ‘quirky’ and ‘cute’,” Boucher/Grimes says. “It’s kind of belittling and sexist that it’s such a part of my perceived image. I really prefer this archetype that exists in Japanese anime culture, like the character Princess Mononoke – she’s very young and cute but incredibly violent and powerful.”

“My skill is not necessarily being a musician. My skill is understanding and predicting culture.”

Grimes/Boucher harbours massive ambitions, like directing a new film version of her favourite book, the sci-fi epic Dune, or writing hit songs for Rihanna. In the meantime, she has begun working on the follow-up to Visions, and she predicts it will prove an even greater pop-cultural mindfuck than her breakthrough. “It’s going in a few different directions, like Skinny Puppy meets dubstep meets ‘Desert Rose’ by Sting, plus a little Taylor Swift,” Boucher/Grimes laughs, adding, “That sounds crazy but it’s not as crazy as it sounds.”