Inside Bexy Cameron’s ‘Cult Following’

With the high profile coverage of groups like the Manson Family, we might normally think of cults as a purely US phenomenon. That, however, overlooks the inconvenient truth that they can spring up anywhere – and that the lines of what we consider “normal” behaviour can easily be blurred.

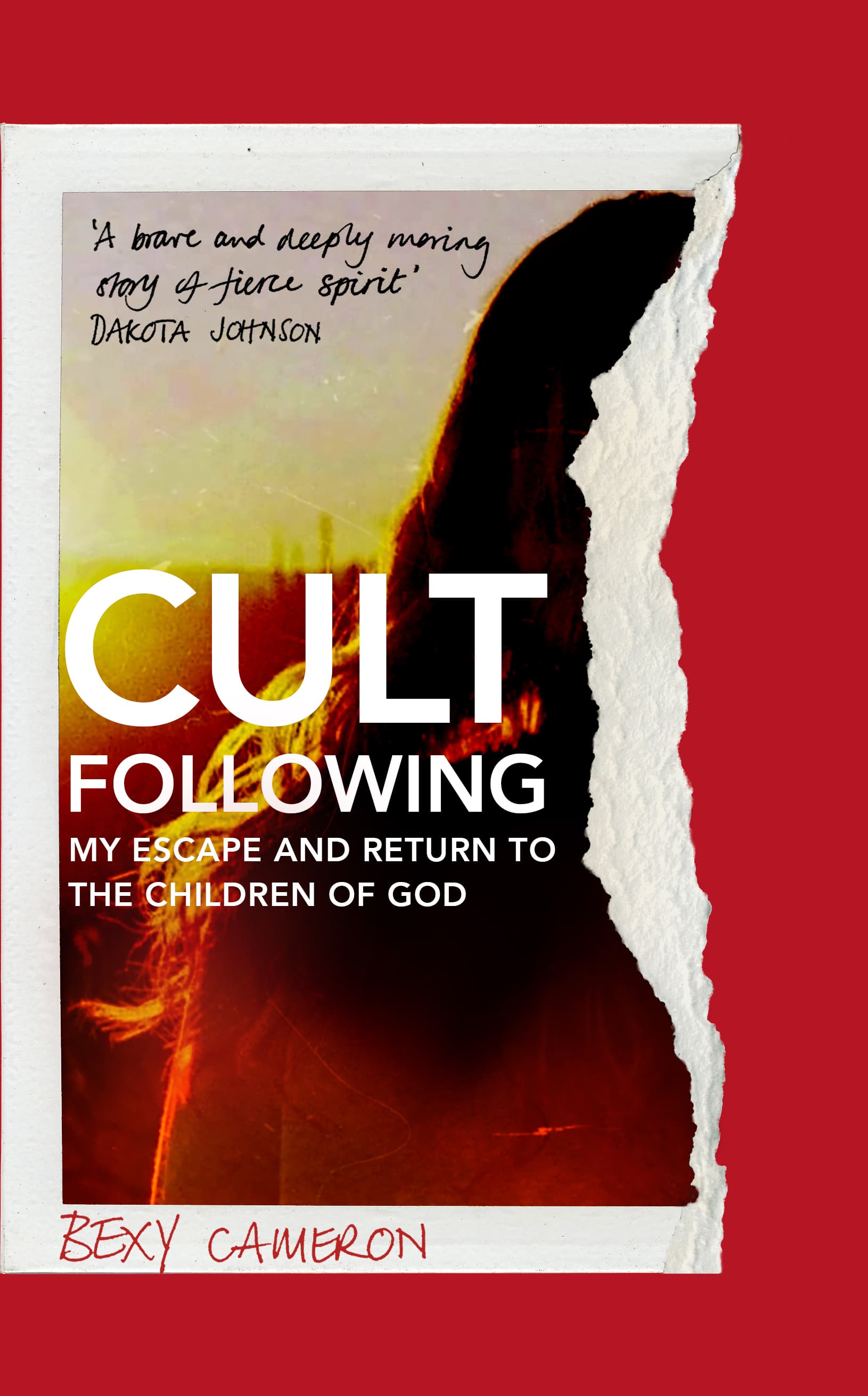

Writer and director Bexy Cameron has first-hand experience of this, having grown up in various parts of the UK within the Children of God religious cult in the 80s and 90s. Her new book Cult Following skilfully explores the memories of that upbringing as they resurface during a trip in her late twenties across the US, as part of a documentary project on religious cults. Intermingling her voice as an adult and as her ten-year-old-self, the memoir investigates the ways that our childhoods shape us while rejecting the narrative that limits survivors to just their trauma. A powerful story of healing and transformation, Cameron’s writing is so stirring that it has already been optioned for a limited TV adaption with Dakota Johnson and Riley Keough attached to star and executive produce.

Below, we speak to Cameron about Cult Following and sharing her story with the world.

To begin, I’d love to talk about your writing style, which is so lively and engaging and not necessarily what I might expect for the subject matter of a book like Cult Following. What was the thought process behind that stylistic choice?

There’s a category called “misery memoir”, which is a well-known genre normally about trauma and written in a very specific [serious] way, because it has to be. But, for me, I’m interested in the light and the dark. The majority of the kids I grew up with, my brothers and sisters, the way we deal with our shit is through humour, making light of it, being sarcastic about it. Obviously, I couldn’t use that tone all throughout book because it trivialises it too much, but humour is how you get through darkness. I was also hoping that writing in that way would give the book a little bit of escapism as well. I often find that if I just read about trauma, it will get to a point where I put the book down.

Definitely, and I think those contrasts are what make the book so impactful. More generally, there tends to be quite a morbid interest in cults among the public: how do you reconcile that with your own lived experience of them?

The strange thing is that I find cults completely fascinating, even though I was raised in one. We might go, “Oh, my God, look, they’re wearing these outfits, they’re chanting this, they do these bizarre fire rituals,” but, at the bottom of all that, basic human needs are the drivers for these religious groups – wanting to find purpose, connection or meaning in life. We can look at groups, and we can see that they might represent a lot of what we fear in humanity but, on the flip side of that, we can recognise a lot of ourselves in the people that join these groups if we allow ourselves to. There’s still a real sense of otherness when it comes people in religious communities but, actually, this is much closer to home than we would like to believe: the demographic tends to be quite educated, middle class, white. When I was [making the documentary discussed in Cult Following] one of my big questions was, “Why did these adults join?” And “what is the experience of the children in these communities?”

That’s such a big question within Cult Following, too, the idea of children’s rights and how vulnerable children actually are when all of their decisions are handed to a parent or guardian, especially in a cult environment.

We are the passengers, or the casualties, of our parents and their decisions and beliefs, for good or for bad. [Children’s rights in cults] seems to be an extremely tricky area, because people don’t really like to get involved in cultural practices and religious beliefs. A conflict of the book is [the point when] a cultural practice starts to come up against human rights, especially of someone like a child. For me, that is when that cultural practice or belief needs to be really interrogated. The hierarchy surely needs to be the protection of a child’s human rights before the protection of a religious or cultural practice, this is not just about people joining a cult, it also stretches out to things like FGM.

Given what we’ve discussed so far, I’m wondering about the process of writing the book: was it cathartic for you? Especially being able to bring out both the voice of your younger self and your adult self?

Writing the book was pretty much any word that you want to throw against it. It was scary, at some points, and in others it was exhilarating. I fell in love with writing, my medium of choice has been documentary filmmaking and creative direction and I’d never really given myself this experience of writing before. But when I was making the documentary [about cults, as explored in Cult Following] and was coming to cut it, the reason it wasn’t working was because I had tried to stand on the outside and make a film about someone else. I realised that, actually, what my soul, body and brain were trying to process was my childhood and I wasn’t allowing that to happen. I really hope that what comes across within this writing is that it’s me on a page.

Did you have any worries about sharing your story with the world?

There’s always a tension between wanting to keep things locked inside yourself, because you don’t want people to know about them, and needing to talk about them. But this [story] needs to be told, because stuff like this shouldn’t happen. The child part of me is nervous about the fact that some of my darkest moments are now on a page and available to the world and there’s the grown-up part of me, a woman in my 30s, that would like to come from a place of strength. But I thought it was worth [that vulnerability]. My dream would be if there were moments on the page that connected to somebody in a way that was authentic and real, and made them feel less alone. If one of those moments happens, then this book is worth putting out there.

Finally, on a lighter note, would you be able to talk about the book’s television adaptation? I know that Dakota Johnson and Riley Keough are already attached.

How wild is that? When I think little me not even being able to watch TV or listen to music [due to the rules of Children of God] and now [my story] is being turned into a series… It’s with really the most wonderful team, who are working from a place of wanting to put stories of women that are relatable and powerful out into the world. I can’t wait to watch it.

Cult Following, My Escape and Return to the Children of God (Manilla Press)will be released on 8 July, preorder your copy here.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.