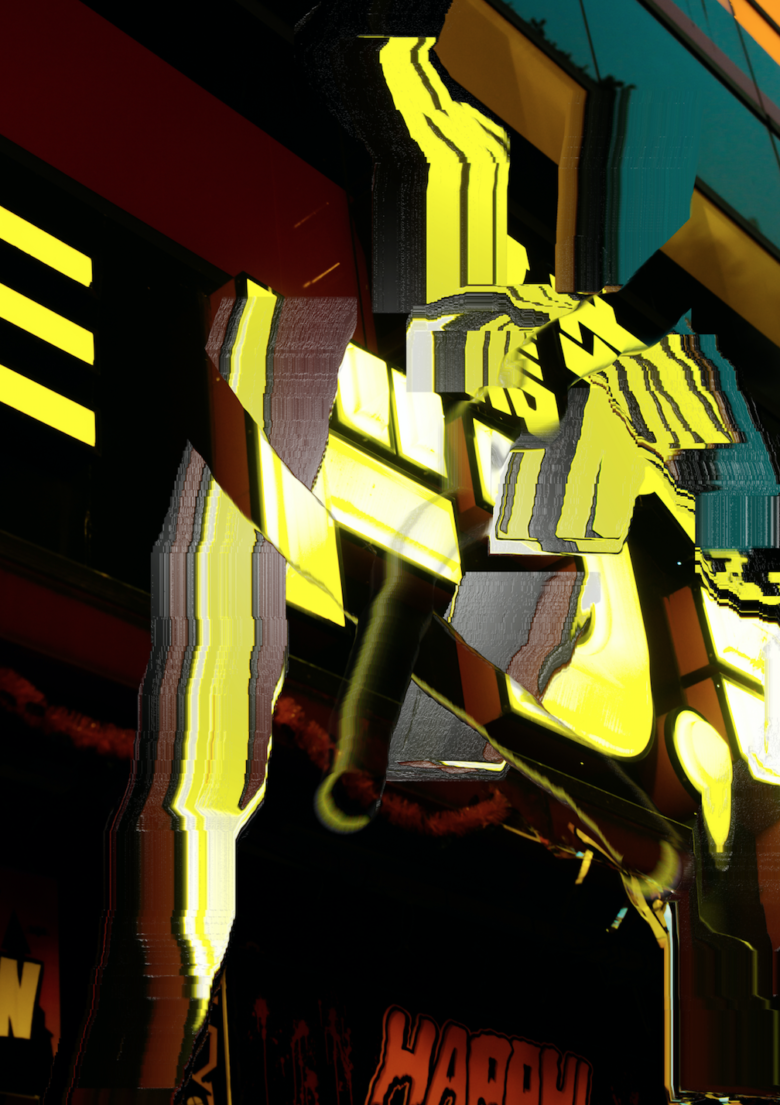

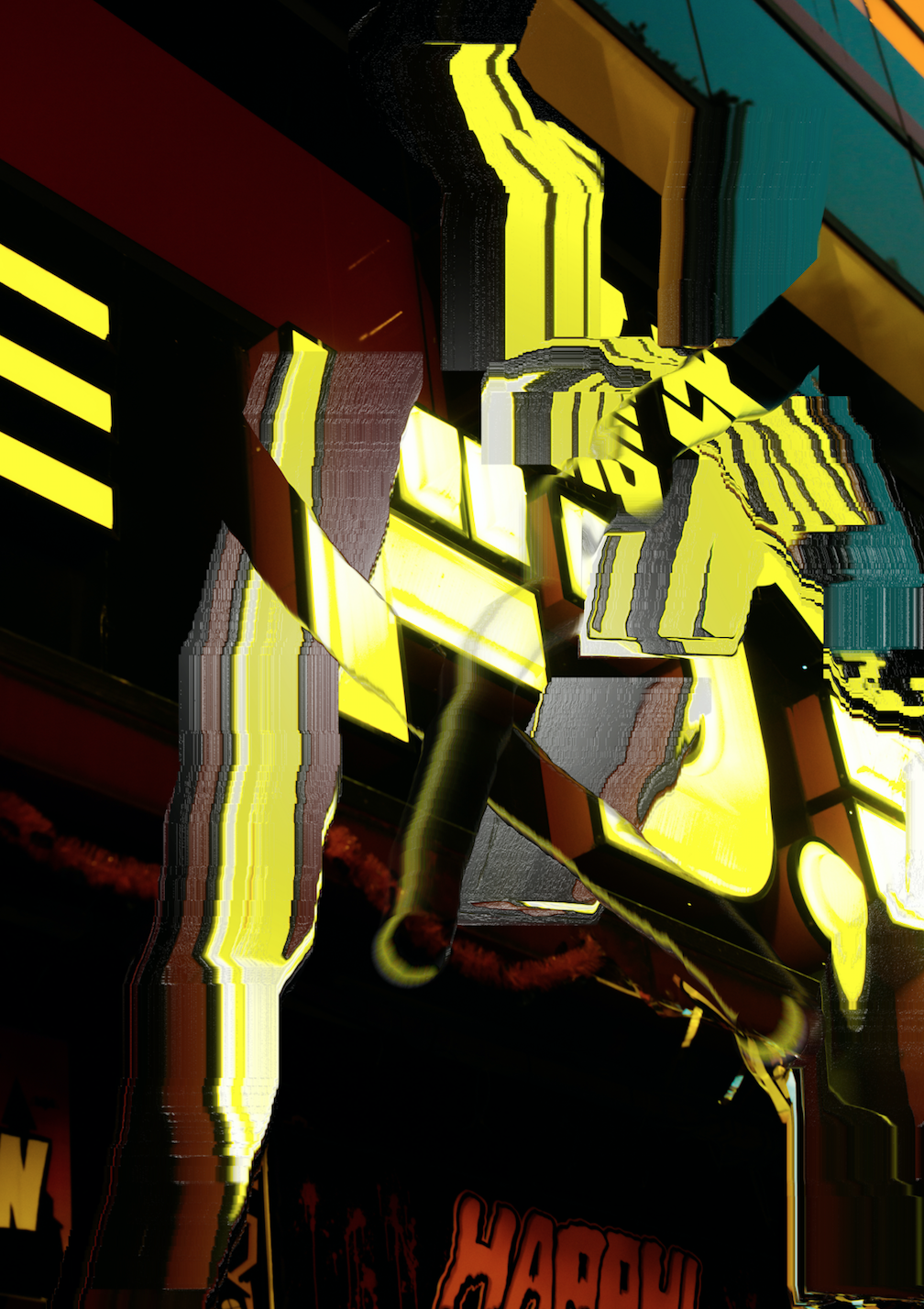

Kenta Cobayashi, blurring the line between digital fantasy and reality

Welcome to the future: let Kenta Cobayashi’s mesmerising photography transport you to our digitally warped virtual world with his lucid colours, pixeled smears, and electric subject matter.

Cobayashi has been ahead of his time throughout his oeuvre, from his pivotal time at the artist collective “Shibuhouse” creating work commenting on the digitalisation of photography, to now, foretelling the merger between creative industries online by collaborating with luxury fashion brands Dunhill and Louis Vuitton. Capturing life in Tokyo, his work not only visualises the cities charged atmosphere but through channelling Japanese folklore of animation he has simultaneously created an alternative algorithmic universe.

To fully comprehend the power behind Cobayashi’s photography, you must first understand the fascinating spiritual perception of technology in Tokyo and Japan. Yaoyorozu no Kami or ‘eight million gods’ is one of the concepts of Shinto, the traditional religion of Japan, it is the belief that nature and everyday objects have spirits residing inside of them. For instance, god of mountain or god of rice, this is why in Japanese culture material things, including technology, are treated with respect. Tsukumogami is the Japanese folklore associated with any object over 100 years old, it becomes alive and sentient because it is ‘possessed’ by a spirit, like the characters in ‘Spirited Away’. In fact, Tsukumogami has been channelled throughout Cobayashi’s work, with traditional photography techniques and technology embodying Japan’s ancient dynamism.

Throughout Cobayashi’s work, he implements this hyper-animated philosophy of technology by editing his photos, you can really feel the image come to life with its fluid manipulation and colour distortion. The photo is not a piece of photography anymore: by uploading it on the web and digitally editing the piece Cobayashi has handed over ownership of the work to ‘the Cloud’ and while the internet is running, it lives through it. Cobayashi’s photography is also a very poignant pointer to Tokyo’s past, referencing animes that embody its inhabitant’s abstracted view of the war and capitalism which created the city’s motif for Western films.

Even in Japan, many don’t know that Tokyo is the worst bombed city in history, on one day during the Second World War America attacked the city with incinerators – over 100,000 people died, and Tokyo was burnt to the ground. Historians now predict if the USA had not won the war, the general who planned Tokyo’s bombing would’ve been tried for war crimes. Although the city’s physical scars have now disappeared, mentally it is still recovering and the memories and feelings of the people who experienced the bombing continue to live through Japan’s animistic imagination. Technology has allowed Tokyo to express its trauma through visual extensions, most famously Akira and Godzilla, which have even become inspirations and symbols of post-apocalyptic, dystopian city-scapes for the Western world.

Cobayashi talks to HUNGER about Tokyo, the future of photography in a digitalised world and about his exciting collaboration with Dunhill earlier this summer.

Hi Kenta, would you be able to give me a brief introduction about yourself and your background?

I was born in Kawasaki, Japan, in 1992. My grandfather and father love Apple computers, so I played applications of Macintosh and iMac in my childhood. I learned contemporary art at university, I lived at an artist collective called ‘Shibuhouse’ sharing a luxury home with over 40 people while I was a student.

What was your first memory of being drawn to digitally manipulated photography?

Children’s paint software “Kid Pix”, I enjoyed digital drawing on a photograph reduced to 256 colours.

Do you think growing up in Japan and living in Tokyo gave you a progressive view on technology compared to those in other countries?

I don’t think Japan is more progressed than other advanced nations. Japan’s consumers have been slow to adopt cashless payments, and new infrastructures such as Uber is hard to become part of the society because the old system blocks them. However, it is interesting that Tokyo has become the motif of various films and animations. The imaginative power surrounding Tokyo is far greater than in real cities. I think that the concept of ‘Yaoyorozu no Kami’ (Japanese animism) and the various worlds of animation reflecting ‘Yaoyorozu no Kami’ is connected to the unique seeing of technology.

What is Tokyo to you?

I like Tokyo as a fantasy, I’m very interested in why this fantasy attracts so many people. Tokyo became a burned field in World War II. Most of the remaining buildings disappeared with the changes of times. However, memories and feelings of the people remained through the animistic imagination. It was extremely abstracted and received as something like a disaster or a curse, rather than human-to-human conflicts on territories by racial and religious issues in western history.

How did 90s video games and anime such as Ghost in The Shell influence your work?

Japanese people regarded the war and capitalism as a kind of disaster or curse and made stories based on that seeing. I think those symbols are “AKIRA” and ”GODZILLA”, and a story about technology such as “Ghost in the Shell” is an extension of this abstract history recognition.

How pivotal was your time at Shibuhouse?

I was able to learn a lot about the relationship between life and art at Shibuhouse. Because there were social misfits who gathered there, necessary to bear the name of “art” for us to live happily. We held a home party every month and gathered people. I interacted with many people and saw that various projects were born. Japan has strong pressure to conform, so it was very important to learn how to escape from it.

What does the term photography mean to you?

One of the traditional perceptions of Japan is the concept of “Tsukumogami”, it is a way of seeing that an anima dwells in a tool that has passed a long time. It means there was no wall between material values and spiritual values in ancient Japan. I think Japanese photographs are interesting because there is the concept of “Tsukumogami”. Through the camera and the editing technology, I feel the dynamism that the passion from the ancient times absorbs the latest technology.

When a photograph is uploaded on the web, what do you think it becomes?

Images uploaded once are almost always copied and re-uploaded by the program. For example, thumbnails are created automatically. Data is degraded by copying and they are processed through human hands and programs. Images are growing, degrading and deforming. Images move like a living thing through the web. I can feel the digital “Tsukumogami” there.

Do you think distortion has a political function in the information age?

There is no perfect invariant truth. The world emerges in the overlap of different systems. Distortion is floating in that space. Political clashes are created by assuming the existence of a complete system without errors. Distortion is a concept that symbolises imperfections and fluctuations for me.

In a lot of your work the human and the digital are blurred together, do you see yourself in the work?

The digital world exists overlapping with the three-dimensional space we recognise, from long before the computer was born. It is a world manipulated by words and numbers, and it is like a dream our brain sees.

What was it like to work with Dunhill?

I was honoured to be proposed with a collaboration with a historic brand. The day before the show, Mark Weston guide me to the studio in Paris. When I touched the product, I was impressed by the handling of the material and the obsession with the silhouette. He tried to renew the rule while taking over the historical context of the brand. It was a precious experience. The images I made were distorted in three dimensions according to the shape of a body gave me great inspiration.

How did you come up with the designs for your collaboration with the designer?

Mark’s team contacted me, and we had video meetings and emails. Mark had been seeing my work in London a couple of years ago and checked out my activity, and he told me that he wanted me to play in this style, aligning his favourite images with the archive of Dunhill.

Recently fashion has shifted towards using AI and virtual reality influencers as models and with digital artists like yourself, do you think fashion and photography will merge into one platform as technology continues to advance?

I think that fashion, digital technology, art, and design will ultimately converge on the architectural question of how to design the human body and the space surrounding it. So, I think that photography dealing with multiple dimensions are a very hot theme in the contemporary art and fashion scene.

And finally, what do you see for the future of photography in a digital world?

It is said that countless sensors connected to the cloud create a ‘mirror world’, I think photography will be like a window that connects the real world to another world. Photography is very interesting now. What is reality? What is space, time, dimension? What does it mean to recognise the world? Photography is functioning as an excellent metaphor to think about that.