Korrie Powell is exploring the nuances of Black masculinity

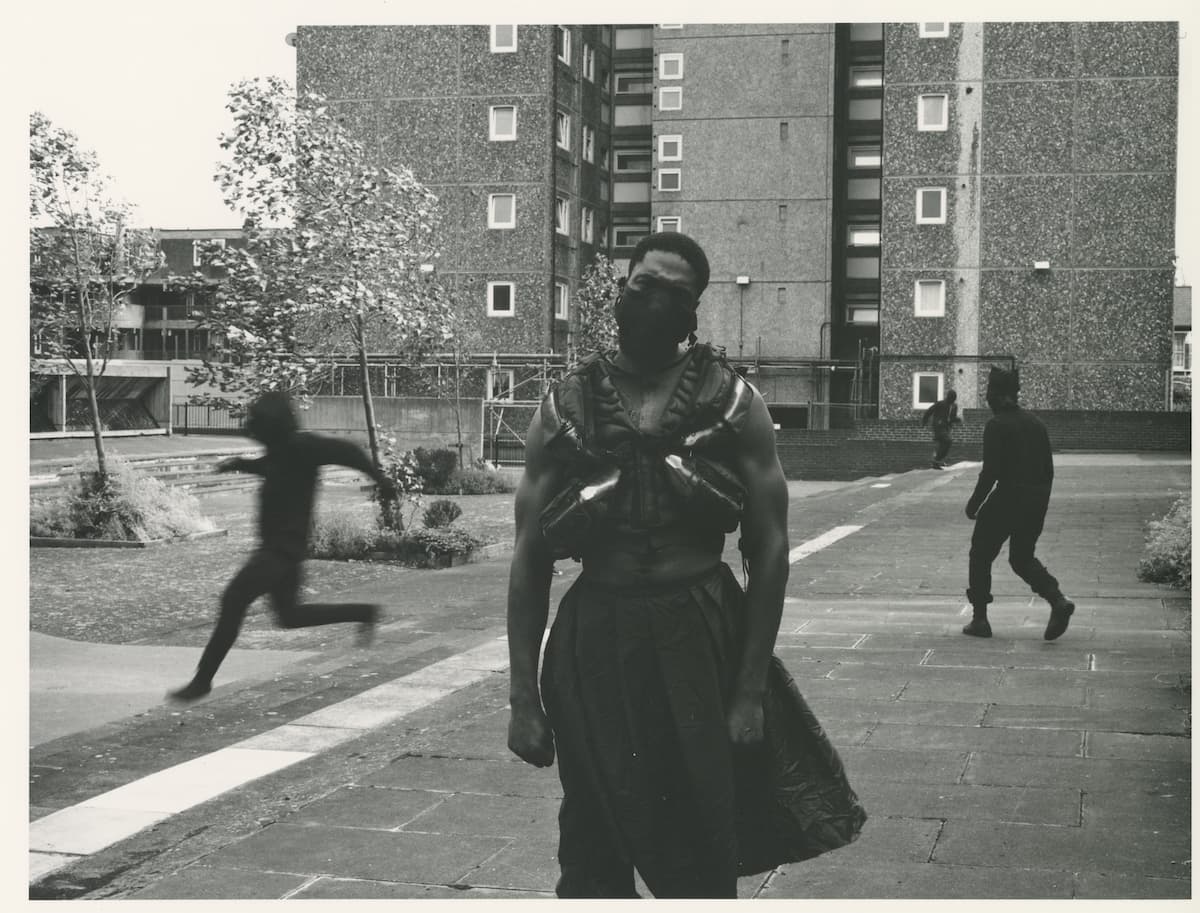

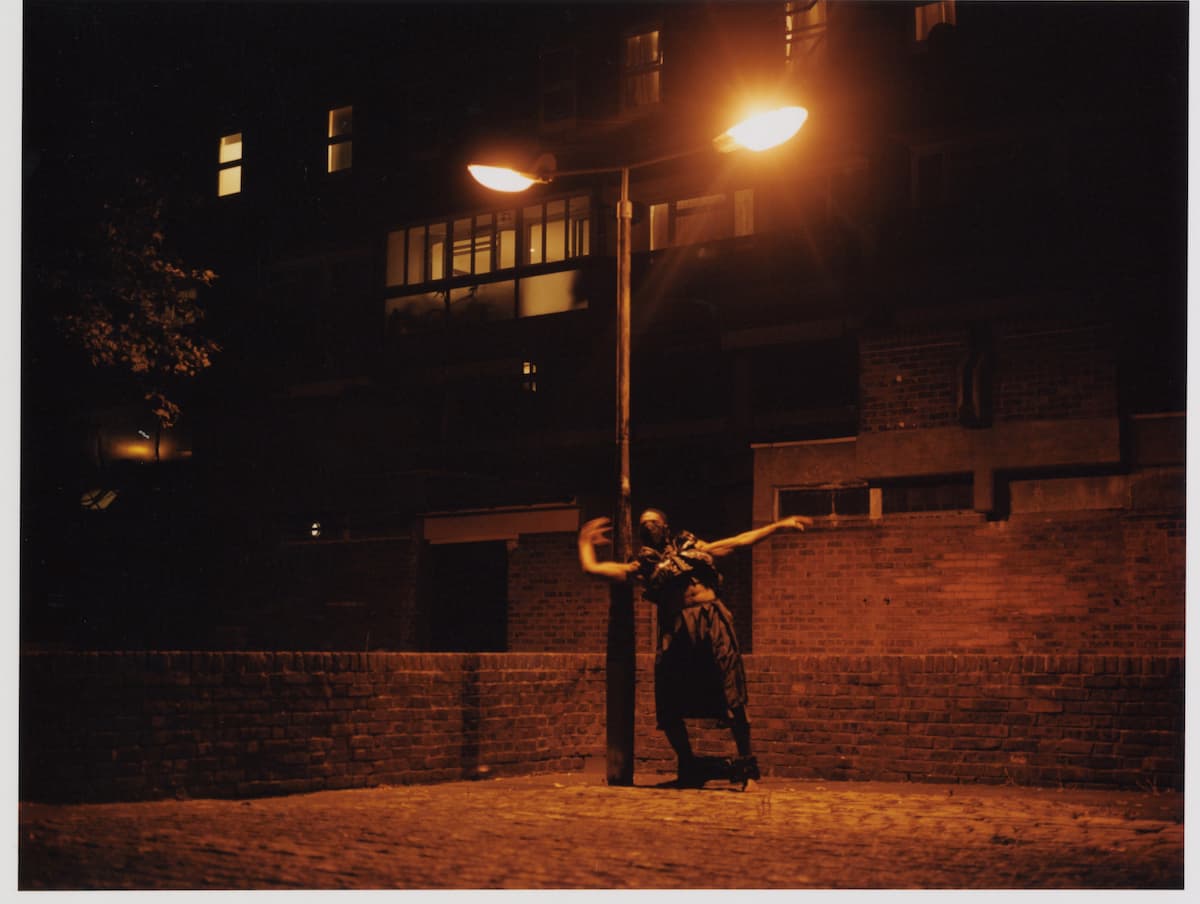

Korrie Powell is a bonafide Renaissance man, spreading his talents over photography, filmmaking, and conceptual art, as well as serving as director of Black Sheep Studios. Based in London with Jamaican roots, he hasn’t been letting the pandemic stop him from making thought-provoking and emotionally-engaged work, such as recent project rage RAGE. Created in collaboration with photographer Jesse Crankson, RAGE encompasses both a photographic series and a six-minute short that reflect on Black masculinity, male mental health and ideas of self with surreal, hard-hitting visuals.

Below, we catch up with Korrie about his creative practice and what RAGE has to teach its viewers.

Great to speak to you. For people unfamiliar with your work, how would you describe your creative background?

I’m originally a director, I started off mostly working on content pieces. As I got older, I wanted to ground my work within more conceptual projects, and that’s when I started to use photography as a way to expand on that. I think now I see myself more as a visual artist, I see visual formats like paintbrushes and whatever best suits my vision, I will paint with that.

Let’s talk about your most recent work with RAGE: if you were to describe the project in one sentence, what would it be?

RAGE is a letter of self-reflection, a thorough and introspective examination of the intricacies of the human condition, as experienced through the eyes of a Black man.

Tell me some of the themes that feed into RAGE?

The biggest influence for RAGE has been growing up Black in London. Being around Black men, I became more and more aware of the complexities of my Blackness. I often experienced moments where I was unable to fully express myself, and I realised that this is in part due to the misconception that vulnerability and masculinity are mutually exclusive.

And what about artistic references?

Artistically, a lot of my influences derived from other art forms such as manga, for example, the beautifully drawn pages in Takehiko Inoue’s Vagabond influenced our camera movements. Additionally, early music video work such as Director W.I.Z’s Arctic Monkeys music video “The View From the Afternoon|. That music video captures the troubles of inner-city London life and the suppressed frustration within men of those environments, and it encouraged me to want to further tell surreal stories but from my own lived experience.

How do ideas of selfhood feed into the project?

The photography series was a good opportunity for me to present the idea of “self” in a different way. One interpretation of the faceless Black men surrounding our protagonist is that they are the physical manifestations of his emotions. The aim here is to explore the themes of masculinity and vulnerability in everyday life and to show that anyone could be struggling to convey their emotions, anyone could be struggling with their mental health, and it is likely to go unseen. The slogan for the project is “at some point we will have to face ourselves”. It emphasises the need for introspection, which is what I am trying to convey with RAGE. Black men and people, in general, tend to neglect themselves, and I think, especially during these turbulent times, it’s imperative that we change that.

Definitely. One thing I noticed when watching the film is that the ideas of vulnerability you just mentioned are partially expressed through costume. Could you talk me through the approach to costume in RAGE?

Fashion Designer Anil Dega created the costumes and the aim was to embody a combination of the traditions that connect Black British youth to our African or Caribbean heritages, with the influences that we grew up with whilst living here. We combined elements of clothing we wear here such as puffer jackets with West African traditional attire, specifically from Zaouli de Manfla, a mesmerising traditional mask dance from the Guro people of Côte d’Ivoire.

Thematically, what do the costumes add?

The bulky exterior, which depicts a physical representation of the barriers that Black men often use to conceal their true feelings, is our protagonist’s armour. In contrast, when he sheds the armour, we see that the inner parts of the costume are stretchy and loose. The patches and holes are a metaphor for his vulnerable interior. The costume in itself is a representation of the whole project, as well as a representation of the relationship between the protagonist and his reflection, and ultimately with Black men and their emotions.

Dance is obviously another big part of the film, what was your approach to movement in RAGE?

RAGE was planned out into four stages: Irritation, False Happiness or Denial, Frustration and Rage. I used these stages as markers for Tyrone [who plays the protagonist] and asked him to express himself through those points. The idea was to get him to get from point A to B to C to D in the most comfortable and natural way, so long as it was a true reflection of his emotions as a Black man. This kept the movements largely improvised, and the process was fluid and authentic. I gave direction when necessary, but allowing him to be free to express his own personal interpretations of masculinity and vulnerability gave the whole piece added depth. We also worked with Simon Hoang, a great choreographer, who helped support us and fine-tune movements.

Ultimately, what are you hoping that people take away from the film?

In essence, my aim here is to try and communicate the feelings of Black men, who are dealing with years of generational trauma and have had no way of expressing their feelings because they aren’t allowed to, their voices have been suppressed. So when they finally get a chance to, it’s not going to be succinct, or coherent, it’s going to be noise, just pure raw emotion and inner feeling.

The thing I want people to take away from this project is that at some point we will have to face ourselves. Sometimes we won’t see a positive reflection of us; it may be a reflection that feels distorted, negative or unwanted but we should never try to bury that or those feelings. Instead, you should embrace it, become willing to challenge your flaws, unlearn what you need to and understand that it’s not about becoming a perfect version of yourself but simply being aware of who you are and loving who that person is.

More broadly, what are your thoughts on the state of the UK film industry today? How has Covid-19 impacted things?

I think that there are definitely a lot of good things coming out of the young filmmaking and wider creative scene here in the UK. In every creative industry there are always unspoken rules and an elitist mentality which permeates through it, but I think as we become more conscious of things, and we begin to bring radical change in other areas of life, this industry will follow suit. Covid-19 has definitely impacted how I and other young people view ourselves and our work. For me, personally, it has made me question what content we should be making, what our roles as filmmakers and storytellers are and what messages we are sending. We have been oversaturated with content that isn’t always meaningful, and that is something we should try to get away from. It has also made me think about myself as an individual, and helped me to prioritise the ”me” before the creator, giving myself time to breathe, and working smarter, not harder.

What’s next for you?

Sleep. Then onto the next thing. We’ll see.

Watch RAGE below and follow Korrie on Instagram.