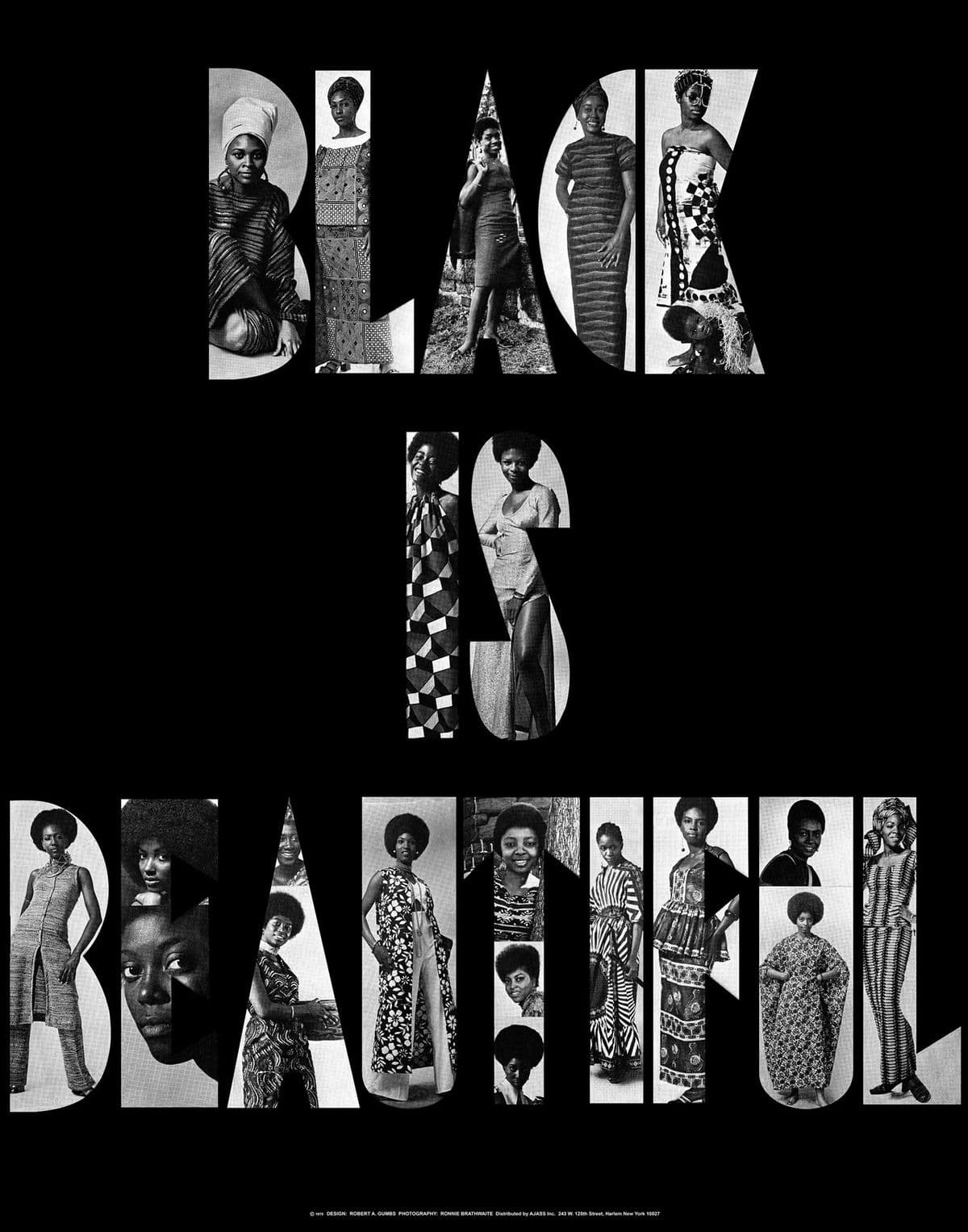

Kwame Brathwaite, Grandassa models and the legacy of the black is beautiful campaign

Precedence for the black mantras of our day, the movement was established in the 1960s and became the zeitgeist for the empowerment movement – dedicated at addressing universal beauty ideals that excluded black beauty from that narrative. Influenced by the writings of Marcus Garvey on Black Nationalism, Brathwaite transported his ideologies through his own texts and photography.

Due to the content of the beauty pageants that existed, Brathwaite became increasingly disheartened by the representation of black women. Their presence alone would not suffice. Kwame Brathwaite believed that black women would dim their blackness for a more Eurocentric gaze. A tale as old as time, dating back to the 1700s. Known to sport elaborate hairstyle, and embellishments appurtenances; they were forced to subdue their eccentricity. In 1786, Spanish colonial governor, Don Esteban Miro incited the Edict of Good Government, typically known as the Tignon Laws, whereby black women in Louisiana were required, to cover their from fear of appearing wealthy and attracting the attention of white men.

From discomfort of conspicuity, over time, women would straighten their hair; wear wigs and weaves that were more reminiscent of white hair aesthetics to combat the condemnation of the “black hair”. This became a common assimilation tactic throughout the African diaspora and the ideal beauty standard for black women. In favour of an Afrocentric embrace, Kwame Brathwaite created his own pageant to celebrate the many facets of black womanhood.

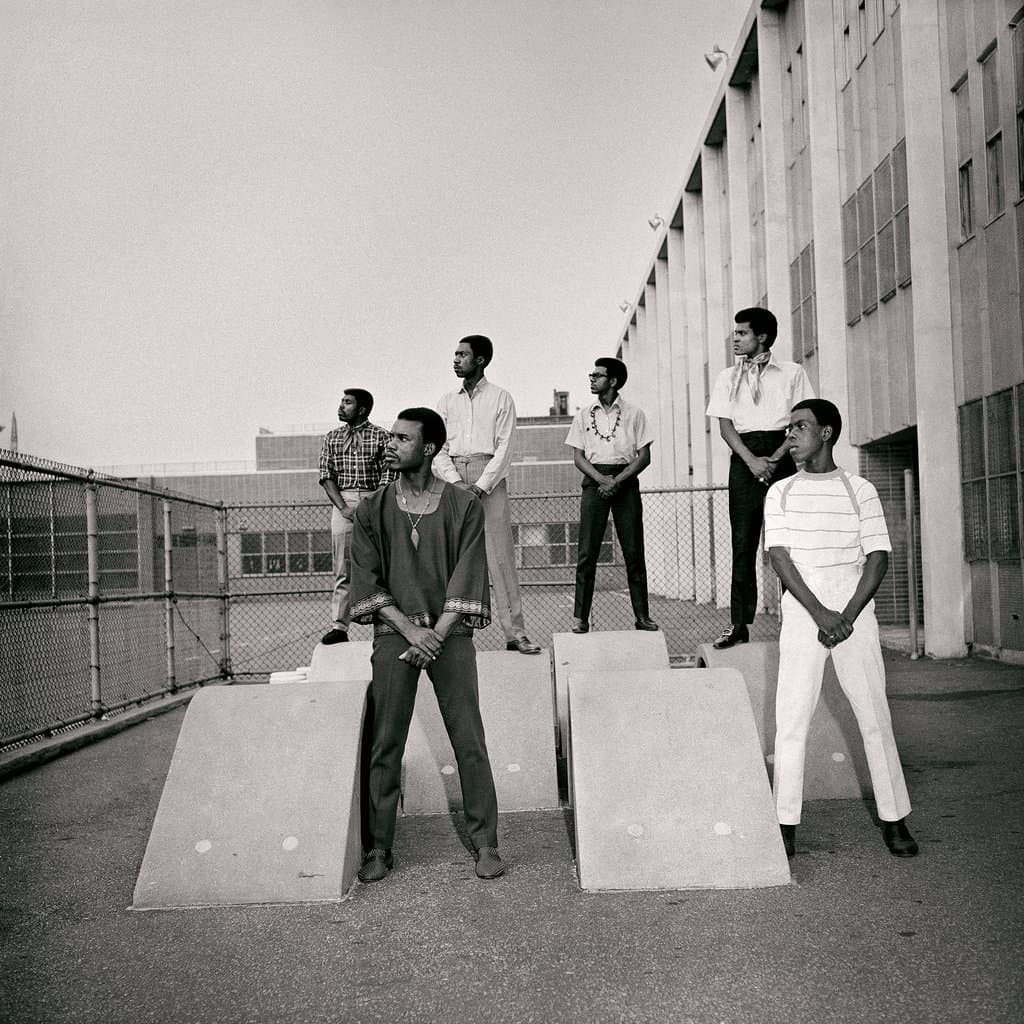

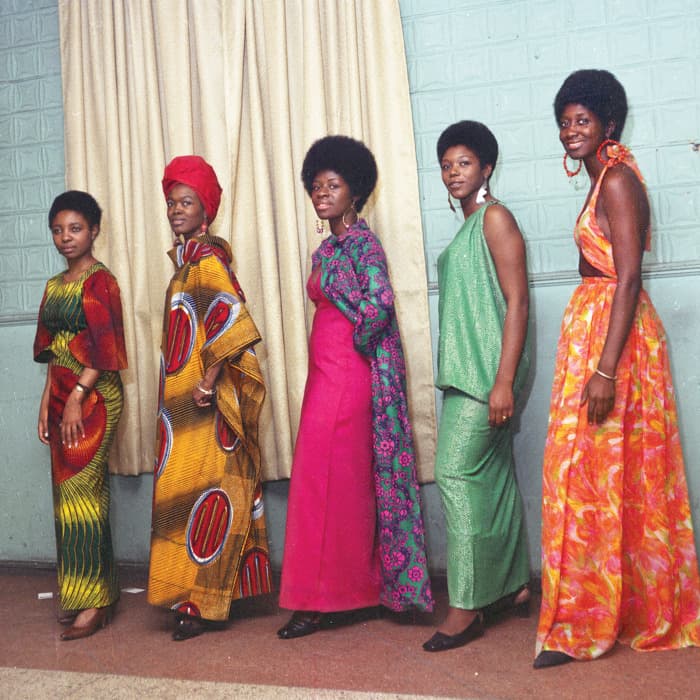

In 1962, Brathwaite founded “Naturally ’62: The Original African Coiffure and Fashion Extravaganza Designed to Restore Our Racial Pride and Standards.”What was originally intendedto be a one off event but as a result of instability and civil unrest of the 60s became resoundingly difficult to ignore. This couldn’t possibly be a one time thing- the humanity of black people cannot simply be reduced to a single session it is more than beauty and fashion- he was disrupting the ecosystem. Along came the Grandassa models the faces of the movement. The name derived from the word Carlos Crooks used to describe Africa, Grandassaland.

Tanisha Ford notes, Liberated Threads Black Women, Style and the Global Politics of Soul, 2015, that, “By wearing African-inspired garments,” the Grandassa Models “were communicating their support of a liberated Africa and symbolically expressing their hope for black freedom and social, political and cultural independence in the Americas.”

Gave people opportunity to showcase their craft from writers, designers, and musician’s artists, for instance,Carolee Prince, who was one of the era’s most innovative designers of jewelry, headpieces, and clothing for the Grandassa Models and bespoke pieces for some of the most notable musicians of the time e.g. Prince and Nina Simone.

The movement forced urgency for dedicate black media outlets, thus the inception of magazine like Essence, 1970, which were established to represent women previously overlooked in fashion, art, and couture.