Whatever your personal appraisals of their work may be, you have to admit that Lana and Lilly Wachowski — who stood at the helm of The Matrix franchise and V for Vendetta — have had a pretty singular impact on Y2K film. In some unsavoury corners of the Internet, however, they’ve never left. Reddit incels hero-worship The Matrix, with the title of well-known misogyny forum r/TheRedPill making reference to the film.

It’s ironic enough that two trans women would inadvertently provide the cultural fuel to white male rage, but it’s even more bizarre when you consider the film with which they kickstarted their career. Before the cyberpunks, Guy Fawkes masks and men’s rights “activists”, the siblings debuted their directorial talents with lesbian neo-noir Bound: a visceral embrace of the subversive “gay outlaw” trope theorised by Leo Bersani.

The 1996 film laid the groundwork for the siblings’ importance for LGBTQ+ representation (their divisive Netflix show Sense8 includes one of the few media portrayals of trans lesbianism), with a sensitive appraisal of masc/femme dynamics in the lesbian community. Bringing the sensuality of female masculinity to the fore whilst exploding any claims that relationships like these function along heteronormative fault lines, it’s a queer cult classic and a must-watch for anyone pining after butch heartthrobs like Christine and the Queens.

Depending on how many queer friends you have, it’s not uncommon to see couples emulating Bound protagonists Violet and Gorky when Halloween rolls around. So, with the witching hour nearly upon us, we break down the vital style lessons to learn from Bound to help you get the reference. Inspired by gender theory savant and meme queen @ripannanicolesmith we also provide a side dish of some of the leading thinkers in the fields of sexuality and gender, helping you to gather the tools for dismantling the heteropatriarchy.

Butch is beautiful

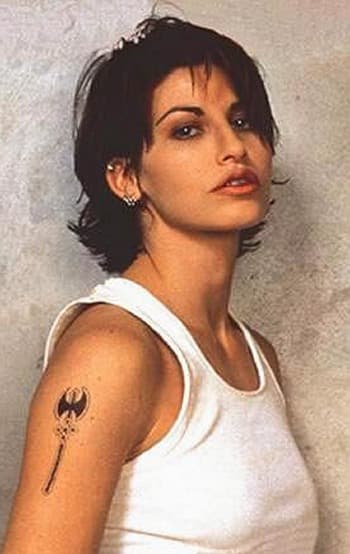

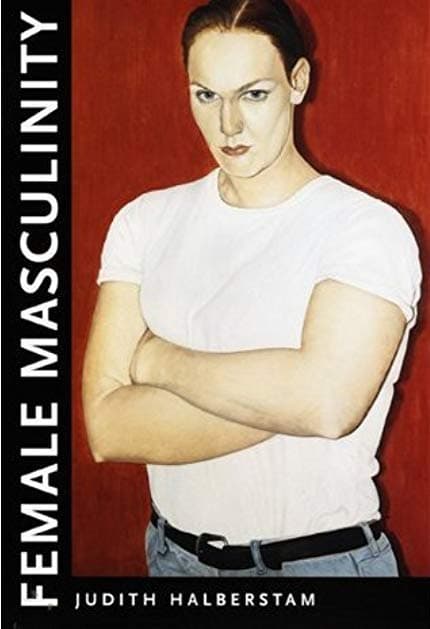

The bilious “men are trash” rhetoric which has sprung from pop feminism has produced painfully reductive appraisals of masculinity. Yet, when we talk about men as “trash” what we really mean is “any unchecked entitlement displayed by white, cis-het, middle class men is trash” — but that’s too much of a mouthful for most. What happens then when we remove masculinity from privilege? This is the premise of Jack Halberstam’s Female Masculinity, a treatise that claims that masculinity “becomes legible […] when it leaves the white male middle-class body.” Gorky, played convincingly by confirmed heterosexual Gina Gershon, could easily testify to this. Her brand of female masculinity has certain similarities with the leather daddies of gay male culture — both in her fascination with motorcycles and leather bars and, more generally, in her understanding that masculinity is all about the spectacle. The ex-con-turned-plumber spends much of her time moodily slouching around in a motorcycle jacket and sleeveless vest, with the kind of shaggy brown hair that would give The L Word’s Shane a run for her money. If anyone needs a lesson in the amped-up sex appeal of female masculinity, Gorky’s wardrobe is it.

Gender is performance

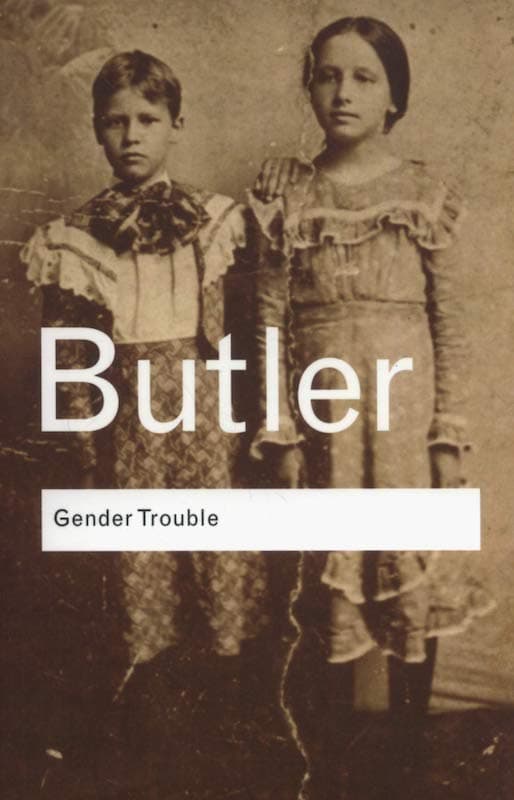

As well as being a step-by-step in how to wear underwear as outerwear (brush off that bustier baby) Jennifer Tilly’s role as mob moll Violet is a masterclass in gender theory. On the surface, with her “I’m baby” simper and kind, listening ear, she exudes innocence. Scratch beneath the veneer, however, and she’s cold and calculating: the kind of person who’d contrive to have her boyfriend murdered and then run off with his ill-gained money. Clearly riffing off of Isabella Rossellini in Blue Velvet, Violet embodies the unattainable feminine mystique of David Lynch’s dreams. If you’ve spent some time browsing the “feminism” recommendations on Amazon, you’re likely to have come across Judith Butler’s blockbuster hit Gender Trouble, which explains that “woman itself is a term in process, a becoming, a constructing that cannot rightfully be said to originate or to end.” Violet self-consciously involves herself in this process, toning up or down whatever stereotypically “feminine” trait she needs to in the moment in order to navigate our gendered, hierarchical world. As Butler puts it: “To operate within the matrix of power is not the same as to replicate uncritically relations of domination.”

read against the grain

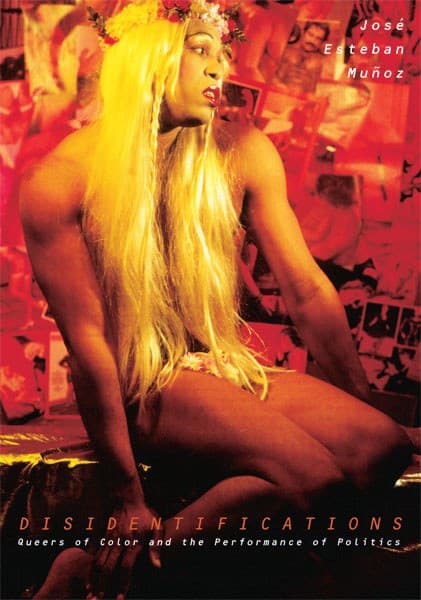

One of the more striking things about Bound is its indiscriminate approach to genre. Despite obviously working within a neo-noir mode, it also combines elements of comedy, erotic thriller, crime and, dare we say it, romance. The most common thread of all these filmic genres, particularly when working within the conventions of classic cinema, is the cisgendered, heterosexual nature of their protagonists. The man of action driving the narrative finds his mirror opposite in the ingénue who provides an outlet for the spectator’s voyeuristic pleasure at the female body. With the romance storyline bubbling under the surface of the primary plot, it is via these characters’ inevitable partnering that the fabric of the film supports the fiction of stable, binary experiences of gender. José Esteban Muñoz’s Disidentifications offers a “get out” clause for those traditionally overlooked by mainstream media such as this – especially the queer people of colour who are also overlooked within Bound‘s lily white universe. He proposes ways of reading and engaging with mass entertainment “against the grain”: methods of inserting oneself into the narrative and refashioning meaning by theatricalising the fissures and fractures of white, cis-heterosexual logic. In this vein, Bound‘s placement of a butch-4-femme couple within a typically overblown Hollywood plot not only helps to expose the gender essentialism of mainstream cinema but also helps to deconstruct the most unconvincing of all our cultural narratives: cis-heterosexuality itself.