Lou Stoppard on curating the exhibition exploring the politicization of the hoodie

Long have clothes been political: from the Bible’s beliefs on linen and wool, to the rationing on wartime fabrics, to the French Burqa Ban, there have been regulations and rules that authority try to put on fashion. And no garment has been vilified more than the hoodie. Communicating social and cultural ideas, it was popularised by Champion in the 1930s as a practical solution for workmen and has evolved to the vital staple it is today.

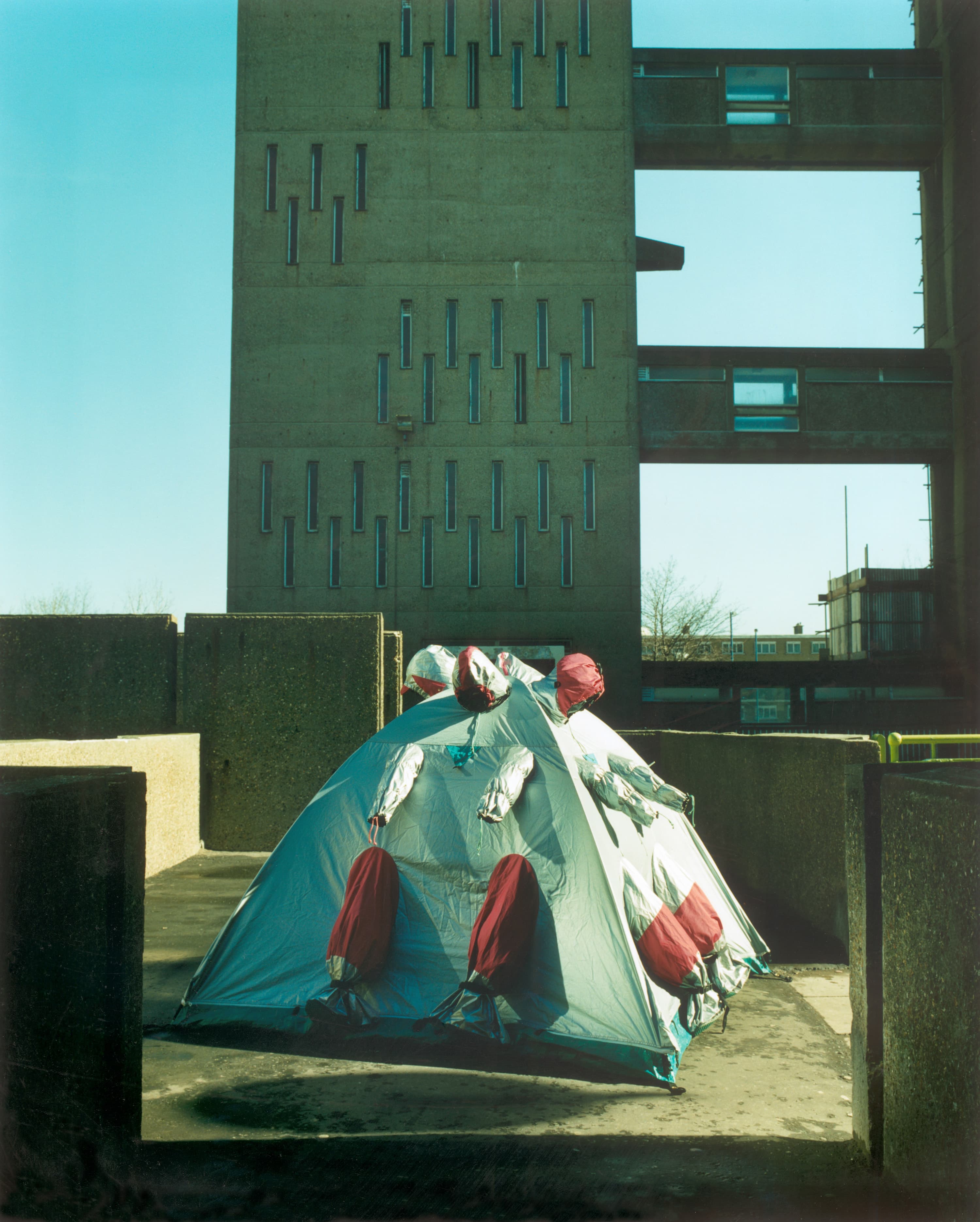

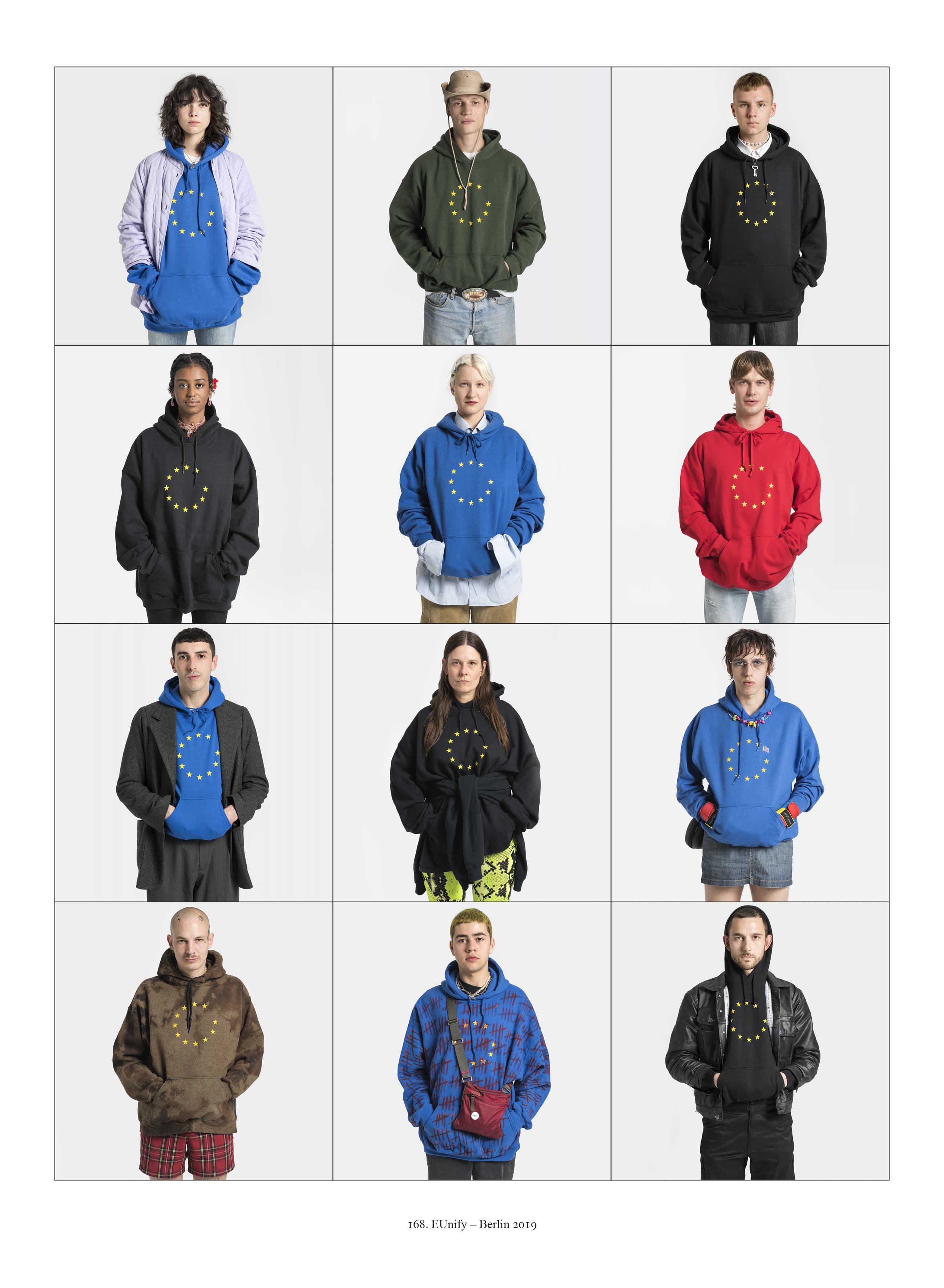

Embodying the classist and racist stereotypes that exist in our society, the hoodie has been named “a signifier of moral panic, banned by certain institutions and dissected by the media as an emblem of inequality, crime or deviance”, but elsewhere is a must-have trend. Dissecting this in an exhibition, curator Lou Stoppard brought together art, garments, film, music and even CCTC to create The Hoodie. Featuring work from seminal artists and photographers such as David Hammons, Campbell Addy, Sasha Huber, John Edmonds, Lucy Orta and Thorsten Brinkmann, as well as designers such as Rick Owens, Off-White, VETEMENTS, and Vexed Generation. Also on display will be specially commissioned installations by Bogomir Doringer and Angelica Falkeling. The multimedia exhibition examines the complex and versatile history of trending, breaking down dress codes, and social reasoning. We meet the writer and cultural commentator to delve deep into the world of The Hoodie…

What drew you to explore the concept of the hoodie?

The hoodie has been in and out of the news for a significant proportion of my teenage years and adult life. In the UK, in the mid-2000s, there was a period of moral panic around the hoodie – young men were getting ASBOs stating that they couldn’t wear them during certain hours or in certain places, shopping centres were banning them, and politicians even started a much-mocked ‘Hug a Hoodie Campaign. Later, in the US, coverage and agitation around the hoodie continued with horrific events like the murder of Trayvon Martin. At the same time, the hoodie was emerging as a key new part of high fashion – a sign of the influence of streetwear and sportswear on luxury brands. So, while the hoodie was being maligned by some media as an emblem of deviance or crime or rebellion, it was also being heralded as a trend in some glossy magazines. It felt like there were so many stories being told that, in turn, reflected broader societal issues. I felt that this garment was certainly the one that spoke the most about this generation, in terms of Western fashion. In a way, I was surprised that no one had done this exhibition before.

How would you describe the hoodie in 3 words?

‘I can’t really.’ The whole point of the exhibition is to look at the broad discussions and debates around it – of which there are many. So three words feels limiting.

How did you find curating a mixed media exhibition for a single garment?

I always tend to work on mixed media shows, that bring together artworks, photographs, printed matter with fashion garments. I think it’s limiting how often institutions separate media out as if they don’t relate to each other. So often artists or photographers or fashion designers are making work inspired by or motivated by similar starting points, for one reason. For this topic, in particular, the mixed-media works help tell the broad stories of the hoodie, such as how it’s been communicated via news media, but also how its inspired artists, serving as a poignant motif for some of the broader themes their works consider. There are many stories within the exhibition – themes covered include the history of hooded garments, the emergence of the modern hoodie, issues around CCTV and surveillance, debates around racial profiling and police brutality, the sustainability of clothing production, the uniforms and styles of subcultures and different music movements – in a way it all serves to show how intense and, often, contradictory existing coverage and discussion of the hoodie has been.

Upon finding collaborators for the exhibition, did you encounter any difficulties?

I was very lucky in being able to have the support of such a great range of artists and thinkers. Every conversation pushed my research forward.

How do you think streetwear has changed the landscape of fashion?

So much: if you look at any runway you can see that.

What is the most iconic hoodie ever?

Of course, the Champion hoodie, which was the original ‘hoodie’ as we know it today is significant to the story of the hoodie.

Why do you think garments are politicized by governments?

I think the hoodie’s story is tied to lots of modern policy issues and debates – whether its protesting and the right to assemble or CCTV and surveillance. I very much see this exhibition as a starting point for conversation, particularly around the way our clothes are regulated or controlled – that’s a relevant topic given the increasing occurrence of regulations and even laws around clothing and face/head coverings. Hopefully, this exhibition encourages debate around these topics, and a questioning of certain norms or habits of thinking.

Do you think art can change politics?

I think anyone who works in the arts hopes so.

What do you reckon the future of fashion will look like after the UK election?

I’m not sure an election will change fashion. I hope that the UK keeps its creativity and that the freedom – of thought, movement and choice – that has defined the UK and, of course, the London fashion scene, remains.