Meet Florence Given: your local “bisexual feminist bitch”

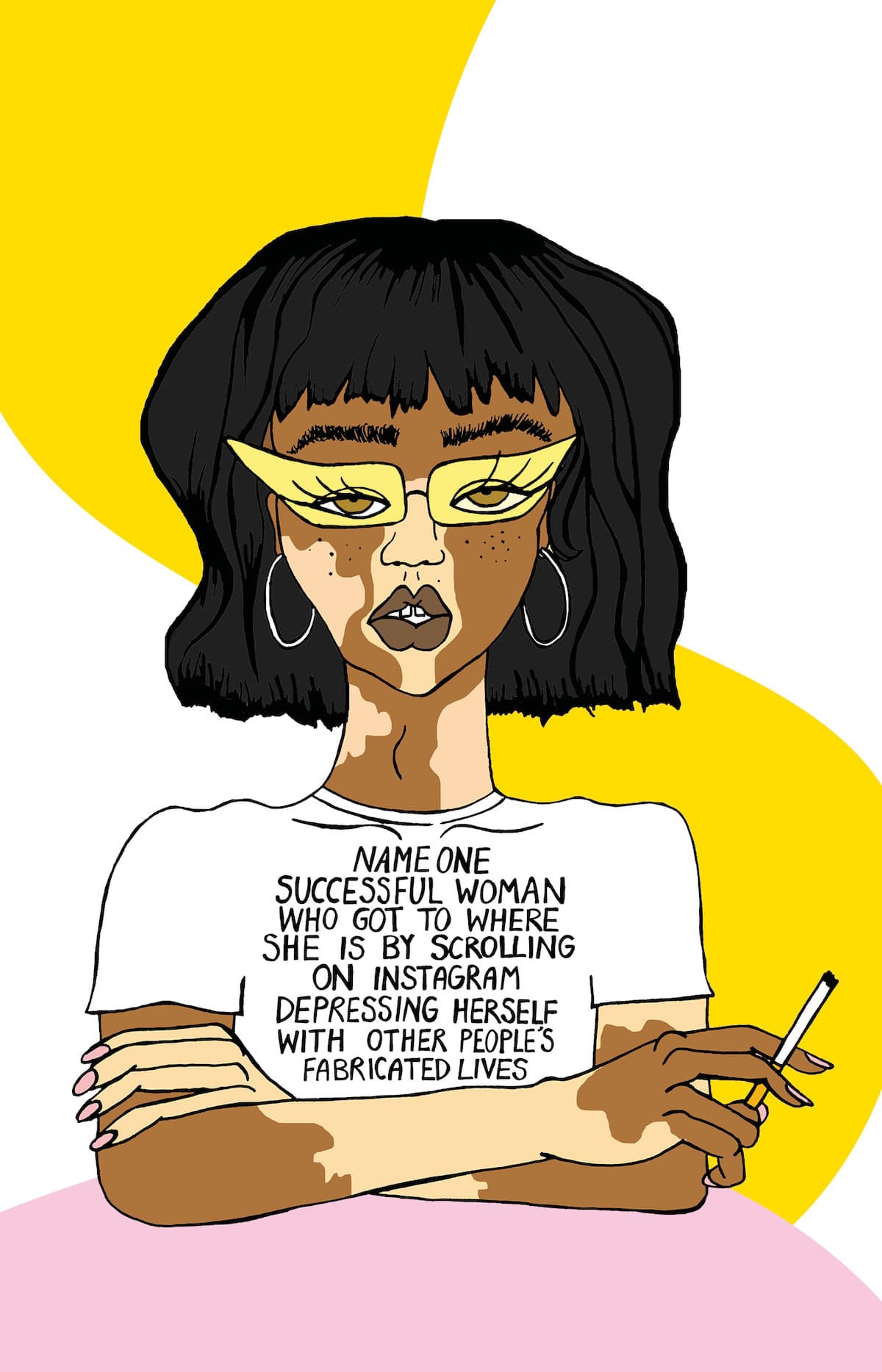

Bolshy, passionate and outspoken, Florence Given is a bright spark translating big feminist ideas to Instagram for a following of over 460,000. First gaining attention for her eye-catching illustrations and tongue-in-cheek slogans — the words “off for a shag” or “love sex, hate sexism” emblazoned across the grid, t-shirts and tote bags — her uncompromising attitude saw her take on streaming behemoth Netflix and its fat-shaming comedy Insatiable with a 100,000-signature-strong petition in 2018.

In the following years she’s continued to grow her platform, opening up about her own journey with feminism and queerness whilst counselling followers through subpar relationships (“stop raising him, he’s not your son” being a common refrain). But, as she explains to Hunger, her brand of zeitgeisty feminism isn’t driven by likes, rather by a radical empathy for all the shit that marginalised groups have to put up with on the daily.

To celebrate her new book Women Don’t Owe You Pretty landing on the best-seller list, we caught up with the bicon to chat gate-keeping, pretty privilege and #DumpHim.

Hey Floss! How about we start at the beginning: what was your feminist awakening?

I think my first catalyst for introspection was at around fourteen years old when I separated from the clique I was in at school. I didn’t like the person I had to become just to keep my place in the group, and once I was out of it, that’s when I started to tap into my own self – through isolation. I stopped viewing women as people to tear down in order to make myself feel better, empathised with their pain, and learned how to navigate their projections to cope with the bullying. I journaled in my diary about my experiences and these uncomfortable truths for years. It wasn’t until I went to art college that I decided to do this with slogans, as I also then learned the terms “sexual assault” and “sexual harassment” and quickly became charged with rage at how normalised this behaviour was, and how I’d experienced it so many times before.

Let’s fast-forward to now: why did you decide to call your book “Women Don’t Owe You Pretty”? I find that title really interesting — prettiness and beauty are, in themselves, really political topics.

It’s not the focal point of my book, but I decided to talk about the male gaze, niceness and making myself small because I had spent a lifetime trying to please others (especially men) and becoming a version of myself that I thought would be approved by them. I had struggled with an eating disorder throughout high school and beyond, and coming out of that I realised how much of my life was dedicated to looking pretty instead of enjoying my life and being present. That my body, under capitalist patriarchy, was used as a breeding ground to plant insecurities and directly profit from me trying to fix them, because it would also supply the solution (for a price). It also caused me to reflect on how if I valued my prettiness so much, that had to mean I treated other pretty women better, and that meant I treated women who don’t conform to societies standard of beauty as less than! An uncomfortable truth, but one every person should acknowledge on some level. We all internalise these ideas and acknowledging them is how we change our behaviour, and in turn, change the world.

Interesting, what are your thoughts on “pretty privilege”?

“Pretty privilege” is something determined by race, class, body shape, gender expression (to name a few), and the closer you sit to the racist, patriarchal beauty standard of defined beauty, the more privilege you have. So, someone like me has a lot of “pretty privilege”. But prettiness is also something that can be applied, through hair, make-up, shaving our bodies, wearing certain clothing etc. Life is easier when we look pretty, when we shave our bodies and when we wear make-up because people treat us better. But on the other hand, when you do look pretty and appear to have made an applied effort with your appearance, this is also seen as an invitation to men for sexual harassment and assault. On the street, in the workplace, in the home; any context where there are men viewing a woman’s body and she looks pretty, she becomes an object. And men don’t respect objects, they’re viewed as something to be used.

So participating in beauty culture is a double-edged sword?

Encouraging women to focus on our desirability, instead of our careers, mental health and wellbeing, is an intentional distraction to make sure we never wake up to the fact that our ‘prettiness’ is a bullshit metric created by men that we’ve been encouraged to value ourselves by, so we remain unaware of our oppression and the fact that there’s still a gender pay gap. Because we’re too exhausted from either starving ourselves because of the latest diet, or focused on how we look in the workplace rather than the quality of the work we’re doing, or whether we’re even being paid enough to be there. If the masses are distracted, they’re less likely to fight back.

What you’re saying really reminds me of Naomi Wolf’s The Beauty Myth. As someone whose work aims to make social justice topics more accessible, have you experienced any kind of negative backlash or gate-keeping from people approaching these issues from an academic standpoint?

People constantly try to minimise the impact of my work because it’s pink, provocative, and extremely feminine. But I couldn’t give a shit. That’s my style. If you don’t like it, move on and read an academic text! It’s just another layer of misogyny, and as you said gatekeeping that some people require my work to reflect academic aesthetics or academic standpoints. I’m not an academic, I talk from experience. The research I do into my experiences is what helps me understand them, write my theories and then that informs the artwork and slogans I make! If the more academic approach is for you, go for it. But not everyone understands that, and these topics I introduce to people in my book are bite-size parts of much larger conversations that I encourage people to delve deeper into with their own research.

You’re well known for your “dump him” slogan and telling followers to end their failing relationships, why did you start doing this?

#DumpHim has been going on years before me, it was after a break up that I added more fuel to the fire, and shared the lessons I learned that could help other people. It’s not easy. I was in a toxic relationship with a man for almost three years, and not a single person told me I deserved better and, even if they did, I probably would have ignored them. I would make excuses for his actions constantly, I didn’t even realise that I deserved better than the treatment I was receiving. I didn’t know that “better” even existed or what it looked like because it was my first relationship!

There are so many reasons people stay in these abusive situations, one of them being a ‘trauma bond’, and also not knowing what abuse looks like because society has normalised the hell out of it. A lot of the work I do now is focused on encouraging people to pick up on these behaviours and red flags of abuse so they’re better equipped to navigate situations before they enter the fog of emotional manipulation and it becomes trickier to escape. I don’t want someone to have to go through what myself and so many others have gone through because they have low self-worth, and don’t think that they’re worthy of anything better.

What are your tips for ethically (but firmly) breaking up with someone?

I can’t tell someone “how to break up with their partner”, but I can guide people with resources to help them see their situations clearly for what they are, and to lead them to the realisation that you always deserve better than discomfort and suffering. Even if it’s just a case of someone draining your energy because they’re not fun enough…you are allowed to leave them. We need to give ourselves that permission. Men have been doing it at our expense, for centuries.

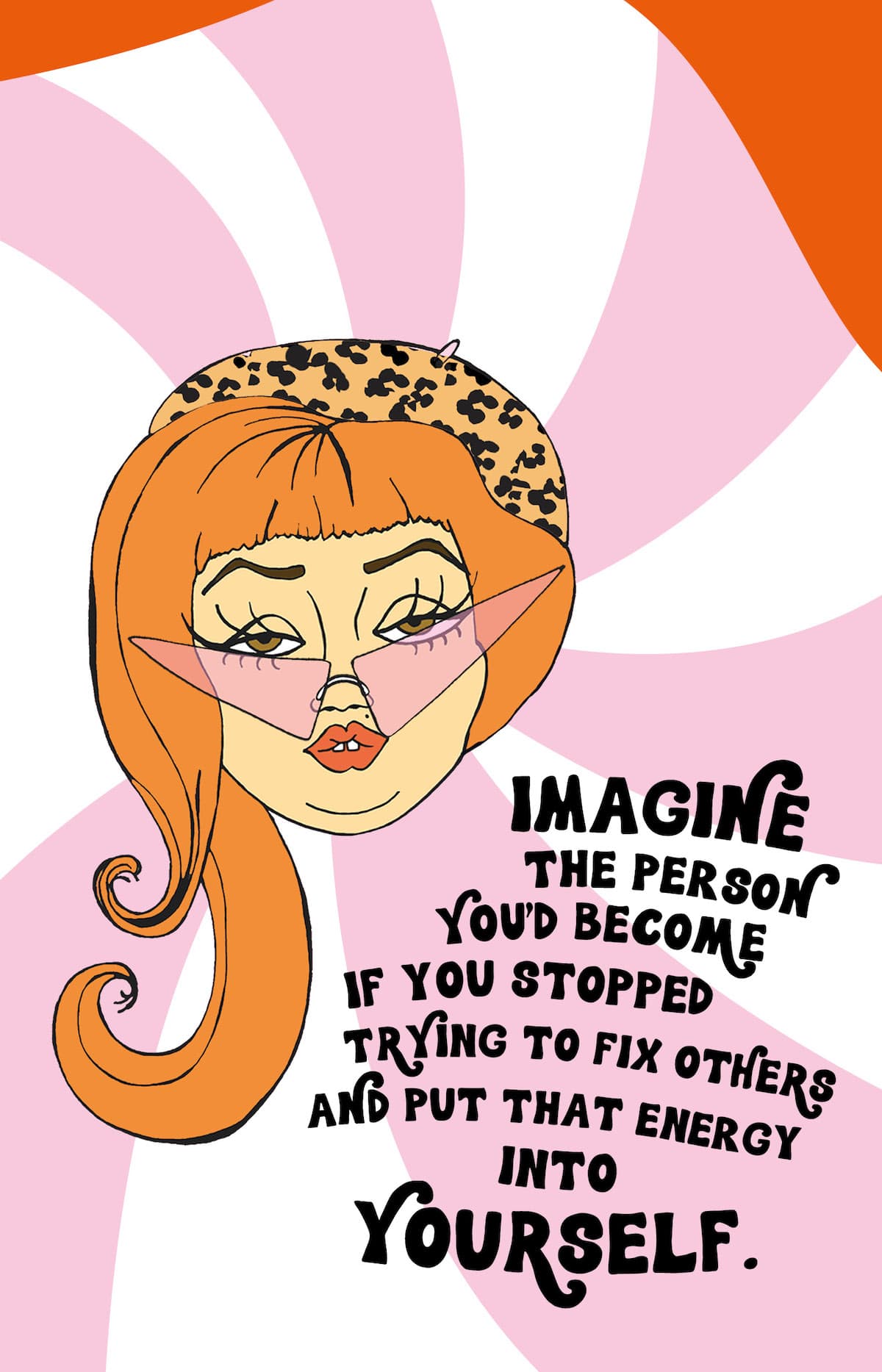

To some degree, queer people and womxn are conditioned to not want to be alone — what are the top things you’ve learned about yourself from being single?

That it’s going to be uncomfortable, but if you stick out the “loneliness” period long enough you realise that everything else was a distraction from liking and getting to know yourself. All the people you dated who were never quite ‘enough’ and all the toxic friends you kept around were probably because keeping the peace and having company felt better than being alone with your thoughts and facing yourself and your insecurities. This feeling of keeping the peace comes from this narrative we internalise about ourselves that says we must be people-pleasing, co-dependent doormats to other people and their desires while neglecting our own in the process. A lot of women don’t even know what they like sexually, because we’ve never been taught to prioritise it. This happens in all relationships regardless of gender, but particularly in dynamics between women and men because the archaic gender-roles are stronger.

You discuss coming to terms with your bisexuality in the book — has embracing your queer identity changed the way you relate to femininity?

Absolutely. Once I came out I started to question everything, and that included my gender expression. I realised that a lot of my authentic-self was being suppressed by my need to be validated by the male gaze and beauty standards. I felt the room to breathe after I came out, and every day I get closer to who I am and unravelling what are my authentic desires, and what are societies desires.

Also on the topic of bisexuality, you discuss queerphobia and erasure you experience in the wider world — have you also experienced this from within the LGBTQIA+ community as well?

There’s definitely a weird in-between feeling you have being bisexual, not knowing where you sit or where you belong. But I don’t care, I’m so proud to be bi. I haven’t experienced any biphobia on dates with women before, but it’s definitely something that men I’ve interacted with have tried to minimise or fetishize for their own desires.

On Instagram you’ve been outspoken about the Black Lives Matter movement and the need to dismantle white supremacy, do you have any advice to individuals who are developing an anti-racist consciousness and want to become allies?

Listen to Black women, read the shit out of their literature and get active in your communities whether that’s an online community, or in your family! I’ve learned, through making many mistakes, that it’s about passing the mic instead of using the mic yourself to speak on behalf of communities. But absolutely, when it comes to calling out people on their behaviour and educating our peers on ways to improve their behaviour, that’s something we should absolutely be taking on. Everything I learned about race was from Black women. A good place to start is Me and White Supremacy by Layla Saad. Game changer.

You can order Florence’s book “Women Don’t Owe You Pretty” here. If you don’t already, follow Floss here.