‘Meet Me in the Bathroom’ directors on 00’s indie sleaze: “There’s less of a sense of danger around music these days”

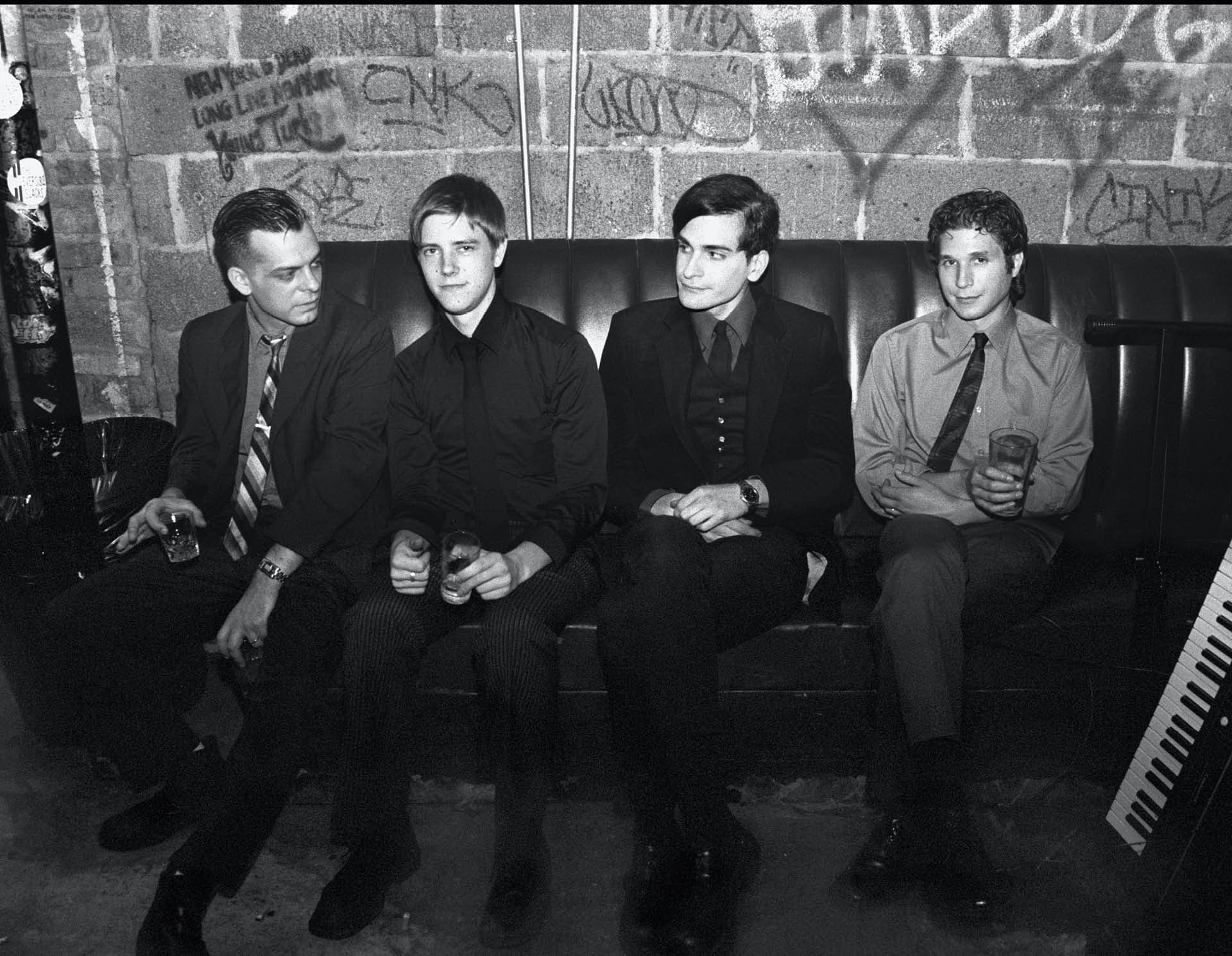

It would be an understatement to say that the music scene in the early noughties was in a completely different landscape to its modern counterpart. While genres were evolving and shifting in and out of popularity, there was one cultural movement that was synonymous with the time: indie sleaze. The likes of The Strokes, LCD Soundsystem, and the Yeah Yeah Yeahs were inviting us into a new era of music, which we hadn’t seen the likes of since perhaps the 70s. And thanks to directors Dylan Southern and Will Lovelace’s new documentary, Meet Me In The Bathroom, we get an even more unprecedented insight into that debaucherous world of New York’s music scene at the time. The film is produced using entirely archival footage and audio interviews, giving a raw and unfiltered exploration of the times, and is inspired by the 2017 book of the same name by Lizzy Goodman. Touching on the effect of the internet’s rise on the music industry, huge societal and political change, as well as the effect that 9/11 had on culture, Meet Me In The Bathroom is so much more than a music documentary – it’s an authentic time capsule. Here, HUNGER got the chance to sit down with Southern and Lovelace to discuss the film’s creation, how the industry has progressed and whether we really are having an indie sleaze revival.

Were you fans of the bands like the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, The Strokes, and LCD Soundsystem, and is that what made you want to revisit this era?

Will: We were fans of those bands, and we were a similar age to them when they started making the music that is featured in our film. We listened to that music and had those records, but I think when we first read Lizzie Goodman’s book, we felt that it was just such an interesting time looking back. It was this moment just as the internet started to come into people’s lives alongside the great music that was being made by those bands. We’ve made music documentaries before, and there are only so many stories you can tell in the music world.

Dylan: There are almost the classic cliches of drugs and band dynamics and all of that stuff. But I think what attracted us to this story was that it is such a specific time and place and that the world has changed so much in the intervening years that it felt like a good time to look back on – just on the cusp of everything accelerating and changing, whether it be technology, culture, the music industry, politics. Within a year of the start of our story, the entire world’s eyes are turned on New York City for a very different reason. It felt depressing to me that it was 20 years ago because I’ve been walking around feeling like it was yesterday until we got into this. You look back at that time, and it’s a completely different world. We thought that it would be interesting to transport people back there if they lived through it or to show younger audiences this scene.

You were based in Liverpool in the UK when this scene kicked off. How was it collecting the footage when you weren’t creating it yourself?

Will: In some ways, it helps that we weren’t there, and there was some distance, and we were not a part of that scene. We don’t have our own memories of going to all these gigs, so we came to it fresh in that sense.

Dylan: It was a completely new way of working for us. We had never made a documentary that’s 100% archived before, so it threw up a lot of challenges that we didn’t expect at the beginning. Before we even started looking for an archive, we interrogated the book and realised what we would have to get rid of and how we could make it work as a 90-minute documentary. We ran our ideal version of the story that we would tell, but then you go into the process of trying to find the archive that allows you to tell that story, and it is a really intense process. We had to do a lot of detective work. We had to follow leads to find clues as to who might have filmed stuff that we wanted to feature. We would spend months thinking, ‘how the hell are we going to tell this part of the story?’ And then someone would save the day by turning up with two records of a show. It was really fun as well. It was just getting access to MTV’s archives or the rushes that didn’t make it into the video or behind the scenes to tell you more than the finished article did. If you can see the rushes, you can see how the guys were feeling on the day. We were just really lucky that loads of people were very generous. It was partly because COVID had everyone trapped in their houses.

How would you say the documentary differs from Lizzie Goodman’s book?

Will: I think in terms of the subject, our film concentrates on the first two to four years of the period she covers in her book. We always wanted to make a film that could sit alongside the book as a companion piece to it, and not just make the book into a film. Lots of what we loved about that book – the history, the honesty, their opinions, and their memories of certain events – we wanted to take the spirit of that into the film we made. They’re very different mediums. Hopefully, we’ve done something different to the book.

Dylan: A book, by its nature, can be expansive and forensic, and it can have 200 separate voices in it, but our intention was to ask, ‘what can we do with a film that you can’t do in a book?’ The answer to that was to create a visceral time capsule to give the immediate feeling of living through that time. We do that through the aesthetic of the archive. We do it by not using talking head interviews as it was not ever going to be that kind of VH1 behind-the-music style documentary. Anytime you hear the band speaking in the film, we wanted it to come from interviews that they had done at that time. We did do some contemporary interviews towards the end of the process, but that was more just to shape the film and to give us some contextual links that we were missing.

You depict a type of hedonism you don’t really see much of nowadays, especially due to the mass closure of nightlife venues around big cities. Do you think the prevalence of social media has sanitised the industry in a way and that hedonism is gone now?

Dylan: I think that’s one of the things we tried to look at in the film. We start with that sequence that almost mythologises as New York of the past, and you’ve got shots of icons like Warhol and Lou Reed and all of those kinds of characters. One of the things we wanted to do, both setting up New York, was to see it as this beacon to artists and people going there to try and join that canon of rock and roll figures. But then, as the film continues, you have this thread of technology coming in, and one of the questions we kept asking ourselves is, ‘why don’t we really look at musicians and artists the way that people did years ago?’ Because we see them on social media, we see what they have for breakfasts; they have sponsorship deals with smoothie companies. There’s less of a sense of danger around music these days. That extends to hedonism because everything’s documented now.

With the documentary being set in New York around the time of 9/11, how was it incorporating that kind of tragedy into a coming-of-age story and a music documentary?

Dylan: We knew it had to be in there because this film deals specifically with that city at this time in history. We were keen to be sensitive and not just put it in there for shock value. That event reverberated around the world, and we knew that to include it in our story, it had to be relevant to the bands and the characters that we were dealing with. We had to look at the response of that community, and we had a real breakthrough when we got the footage of Paul Banks from Interpol on the day of 9/11 out on the streets with debris falling from the skies. He is picking up leaflets about giving blood. Karen O talks about how the only way she could deal with the anxiety that she had after the trauma of that event was to go further and further on stage. The thing that the book did that made it really interesting was when people were talking about an act of terror happening in your city. It can happen here, and now, we might as well do what we love doing. This apocalyptic aspect also fed into the way that the city changed and the way people began moving over to Brooklyn. It was essential that it was part of it, but we were aware that we had to include it in the right way.

Do you think we are seeing an indie sleaze revival right now?

Will: The phrase still makes me laugh.

Dylan: It has sort of been rebranded. Is 20 years a good number to start looking back at things? All of those artists are still making records and still touring.

Will: I’m sure in some way Lizzie’s book has helped people get interested in that scene again. Maybe it is just a 20-year cycle.

Dylan: Nostalgia for the 60s happened in the 90s. That’s the amount of time when the people who lived through it hit that age where they become nostalgic or reflective about the past. It could be that, or it could be that for the younger generation, there isn’t a scene like that anymore. It’s all fractured, and music isn’t consumed in the same way. And the popularity of the indie sleaze Instagram account with tons of followers might be the same thing as how I was really interested in punk when I was younger. It’s people looking at the past for things not visible in culture today.

Did you have any revelations or thoughts about how we use the internet now whilst making the documentary?

Will: It’s just so different than it was in the book. I love when they are talking about promoting their bands by making their own flyers and leaving them in bars. The internet was used in a more basic way in this period because there were message boards. Now, you don’t have to be in the same place to hear and see music; you can be anywhere. You discover music completely differently now. Could this scene or movement ever happen again in the same way?

Did you feel more nostalgic about the time after making the documentary? Especially as it has been described as the last great romantic age of rock and roll.

Dylan: At the end of making this documentary, I don’t think we’ve felt nostalgic about it at all. It was such a long, arduous process. Personally, I try not to get too nostalgic about things. I try to listen to as much new stuff as I can and I don’t want to be one of those people that’s just dwelling on the past. I’m sure something exciting will happen again at some point; it is just going to be in a different way that no one expects.