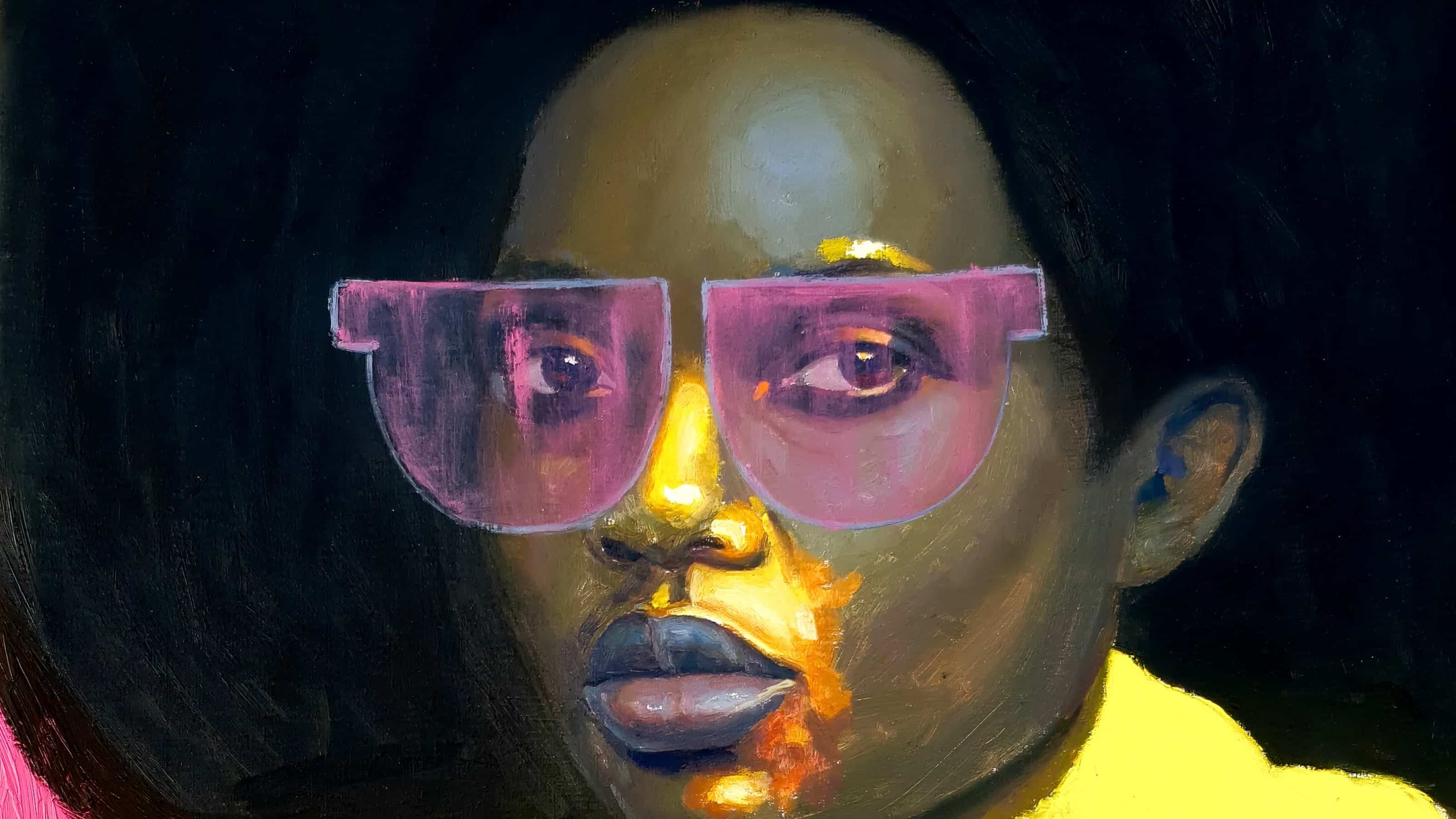

Meet the Nigerian artist whose muse is Black women and their natural hair

The Nigerian artist Oluwole Omofemi certainly has a muse: the Black woman and her natural hair. For Omofemi, hair is a metaphor for freedom, power and identity, and through his wonderfully evocative portraits he seeks to uplift Black women to be themselves and embrace their independence in equal parts. “My message concerning Black hair and Black women is unequivocal and direct,” says the artist, who recently gave the Queen a bold crown of black hair in a new Platinum Jubilee portrait. “For a long time African women have been deprived of many things because of their gender. My paintings aim to empower women to stand and fight for their constitutional rights.”

Born in 1988 in South Ibadan, Nigeria, to humble beginnings, Omofemi was singled out as a child for his artistic talents. Tapping into the themes of his seminal work at a young age, he learnt about the civil rights and natural hair movement of the late 1960s and 1970s from his grandfather, who wore an Afro. His grandfather’s wisdom and guidance impressed on the young artist the importance of preserving culture, heritage and historical traditions, which is evident in his subjects. They are often adorned with halo-esque Afros or have completely bald sakora hairstyles, as well as scarification marks to identify their roots. As Omofemi puts it so eloquently: “Hair speaks volumes about our values and cultural heritage as Africans.”

Here, the artist discusses the motif of hair, how emotions influence his far-reaching creativity and his desire to champion Yoruba traditions.

JAMILAH ROSE-ROBERTS: Who or what inspired your artistic beginnings?

OLUWOLE OMOFEMI: A series of events influenced my artistic journey. But initially and most importantly, my childhood experiences inspired and formed a significant part of becoming the artist I 101 am today. There was a particular time when I had the privilege of living with my maternal grandfather and a neighbour of ours saw my interest and talent in painting and continued to reaffirm and encourage me. This particular neighbour advised me to “never give up on my dreams” and ensure I did everything to make sure that I fulfilled my goal of becoming a professional artist.

JRR: As a Nigerian, how has your art affected your journey? As part of the African diaspora, I understand there can sometimes be a lack of familial support. How have you overcome this?

OO: Art has immensely and positively affected many of my life choices and decisions. While I was growing up, my parents and maternal grandfather collectively had different plans for me. Hence they did not support my intention of becoming an artist. In fact, the thought of being an artist from the envi- ronment I came from in Nigeria was very much alien and unacceptable. My father wanted me to become a lawyer, while my mother had an entirely different plan. Although this was the case, I was able to take charge of my direction and firmly stood my ground. I was happy and ready to embrace the challenges of said choice. I went to the extent of doing “petty jobs”, such as a sales boy and a car washer to survive.

JRR: Your motivation to succeed is exceptional. What is your favourite medium for your artworks?

OO: My favourite medium is a combination of oil and acrylic paints. I also include spray paints, depend- ing on the type of piece I am creating or my mood. Each work requires a large amount of effort and skill – from the beginning to the final stroke. Hence my technique results from my constant dedication to my work, which has become part of me over time.

JRR: It sounds like you share your own emotional experience when painting. Do your emotions impact on your creativity?

OO: My emotions have greatly influenced my paintings and have also helped my creativity as an artist in many ways. As an emotional being, my feelings have dictated the subject of my work, along with my choice of colour palette. For example, the painting In Her [2019] was created when I lost my paternal grandmother to the cold hands of death. At that moment my emotional state of mind formed that wonderful piece of artwork.

JRR: Inclusive of your emotions, you’re something of an activist, as your portraits champion social-political issues. Why is this so important to you?

OO: My assertiveness and relevance as an artist can be attributed to many key factors. These include diligence, perseverance and hard work – all of which I had engraved on the tablet of my heart. I also like to conduct research before beginning a new piece and strive to bring impact and assiduousness.

JRR: Your paintings of women as antelopes are red- olent. Having learnt about Yoruba tales, according to Ijebu lore, the antelope became a water spirit because of its unwilling involvement in human attempts to capture bothersome spirits. Can you tell us more about why you chose the antelope as a muse?

OO: Well, my perspective or usage of antelopes in my paintings is somewhat different from the general interpretation. Some animals generally possess some characteristics that are sometimes attributed to human beings because of our belief system. An example of this is when someone says that a person is as bold or courageous as a lion. That doesn’t mean the person is a lion, he is simply described with an attribute of a lion – to show how strong or courageous the person is. I have noticed with antelopes that they communicate decisiveness and speed of action, which requires us to step out of our own heads. To stop thinking singularly but try to start to feel everything. Antelopes possess some interesting characteristics that human beings should be encouraged to imbibe.

JRR: You’re deeply inspired by African and Black women’s hair. Are you seeking to encourage Black people to embrace their natural hair, and thus their implicit power and freedom?

OO: My message concerning Black hair and Black women is unequivocal and direct. For a long time, African women have been deprived of many things because of their gender. My paintings aim to empower women to stand and fight for their constitutional rights. To end any schemes and unfortunate vices fashioned to put a clog in the wheel of their progress.

JRR: I feel empowered by your words! Can you elaborate on your perception of what hair represents?

OO: Where I am from, hair is very peculiar and is seen as mystical. Apart from the fact that hair defines the sumptuous beauty of African women, it is also spiritual. It is a symbolic representation of what hair means and transcends the literal interpretation we give. In the past, hair, particularly Afro hair, represents a movement. It is an expression of resistance, reclamation and actualisation. In this period, when we are still faced with similar racial and tribal challenges, it becomes even more pertinent to deploy the same attitude, given the current globalisation of interactions, whereby cultural clashes are inevitable. Hair speaks volumes about our values and cultural heritage as Africans. Focus- ing on our unique hairstylings helps to salvage our negritude in the face of hybridisation as we confront political disruptions leading to expansions in the diaspora.

JRR: I love your depiction of African women in Boss Lady and Fearless [both 2021]. The Yoruba tribal marks are scarifications, which are specific identification and beautification marks designed on the face or body of the Yoruba people. It’s a cultural signifier that indicates a person’s tribal heritage and it’s dying, sadly. Can you tell us more about this body of work?

OO: As Africans, we respect our culture and traditions as it constitutes part of our way of life. As you pointed out, the Yoruba tribal mark signifies identity and beauty. Each tribal mark is immediately deciphered by virtue of a person’s tribe, spiritual protection, family or patrilineal heritage. During the transatlantic slave trade, tribal identification became important. Consequently I do my best as an artist to rejuvenate this dying tribal heritage through some of my works.

JRR: In Her is a piece that really stands out – the artwork portrays a bald woman against a colourful background, adorned with words and phrases such as “She is God”, “Queen”, “Joy”, and “Love”. I sense that it is a very personal work.

OO: The story behind the painting was inspired by a sad event in my life that I am still struggling to grasp. The bald woman in it represents my paternal grandmother, who died of cancer. After undergoing some tests, it was discovered that the situation would not have deteriorated to that extent if she had paid attention to her health. She battled until she couldn’t any longer. It was a moment I wished had never happened. The painting was to keep her memory alive and signify hope and love for those battling cancer.