Alessandro Michele, Creative Director at Gucci since 2015, loves to talk about “freedom.” At the beginning of his tenure, he defined his ideal Gucci woman as sexually and creatively liberated: “A woman whom you’ll never know if she has a boyfriend or a girlfriend, a woman with great freedom of expression.” Through his collections, Michele defined his vision of luxury as synonymous to eccentricity with the clashing prints and unwieldy silhouettes: looks created for someone who has sufficient affluence to never have to worry about something as pedestrian as fitting in. With his Cruise 2020 collection, he went as far as to liken his Pagan-inspired offering as a “hymn to freedom.”

Yet clothes are not necessarily freeing. False binaries dividing “male” and “female” have been played out in clothes, meaning that some children are obliged to wear items that correspond to a gender they do not identify with. Workers in textile manufacturers across the world are trapped in a cycle of poor labour conditions and unfair (sometimes even entirely non-existent) wages. So, looking at the facts and picking up on the notion that fashion — particularly fashion coming with a Gucci price tag — isn’t as liberating as he might like to believe, Michele decided on a pivot of direction for SS20.

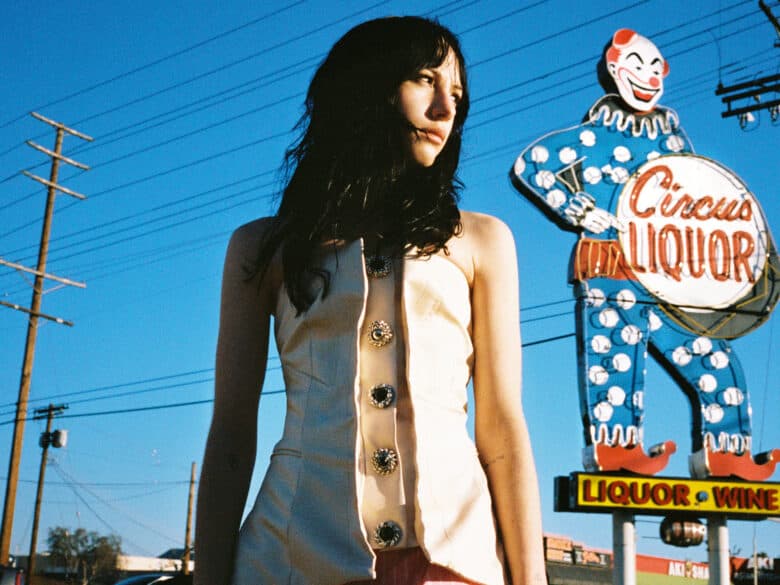

Seemingly having torn through an introductory guide to Michel Foucault at some point in the past 6 months, Michele’s most recent runway offering was an exploration of fashion as a mode of social control, opening with pared-back, ivory creations representing “the normative dress dictated by society and those who control it.” Drawing parallels between fashion and the loss of freedom is an unexpected critique for anyone in the fashion industry – particularly in a late-stage capitalist society so keen to sell consumers the illusion of choice. However, it’s novel coming from a man whose work has long been couched in the language of female empowerment.

If we’re to follow Michele’s train of thought here, it’s worth exploring how fashion might be said to inhibit our autonomy. Fashion could be said to exert control on show the boundaries of “acceptability” are drawn on both an intellectual and corporeal level. Firstly, the vicissitudes of fashion, and particularly the collections pumped out by big-hitter brands, play a large role in creating our definition of what constitutes “good taste” and laying down what we “should” be wearing throughout the next season. Secondly, the exceedingly narrow standards of beauty promoted by these same brands — which is overwhelmingly skinny, young and white — works on the body by creating a singular definition of “bodies that matter” vis-à-vis the dominant paradigm. Those who do not fit into this definition, self-discipline themselves in an attempt to reach these defined beauty standards — sometimes altering their appearance through diets, products and surgeries.

Whilst none of these are new concepts, they’re worth repeating. But the delivery at Gucci left much to be desired. Sending his talent down a conveyor-belt-cum-catwalk, the unique staging downplayed models’ agency and called to mind depictions of human cloning in popular culture where archetypically beautiful carbon copies are squeezed, one after the other, out of machines. To begin, the complete deindividuation of the featured models seemed like a painful misstep. The dehumanising mistreatment that has been widely reported in the industry makes it clear that many in the profession are already treated as just a body, rather than as a fully-fledged human being.

That straitjackets were featured in the opening interlude is also concerning: suggesting that Gucci has learnt little from its previous scandals regarding the use of offensive imagery in its collections. Whilst obviously fitting in with the motif of restriction, the garments seemed to be selected simply on the basis of “shock value”. Repurposing one of the most stigmatising images from depictions of mental health, the young woman held against her will in the hospital ward, à-la Girl, Interrupted. For anyone that has experienced acute mental health troubles, it is cultural images such as this that prevent us from reaching out for help when it is needed.

So, what exactly was Michele’s motivation? These garments are not due to be sold in stores, meaning that they clearly fit in with the wider thematic concerns he intended to plug with his show. As well as talking a lot about control and sex (the SS20 show was entitled “Gucci Orgasmique”) and being one of the first Western thinkers to consider gender as a social construct, Foucault was interested in physical spaces that inhibit human agency, especially the mental health ward. Defining “madness”, as a form of deviance from mainstream society, it appears that Michele was trying to sell the notion that his Gucci muses are the kind of “rebel women” who would be burned at the stake as witches in the 1600s.

In conversation with 032c in 2018, Michele likened fashion to a “prison,” but assured that he was in the process of “restoring its creative freedom.” As this opening segment (equally austere and alarming) segued into ‘70s flares, block brights and Iris Apfel-esque eyewear Michele seemed to be doubling down on his message that if anything is to save you from becoming a fashion clone it is Gucci. Yet disrupting Michele’s on-brand thematic flow came an unexpected act of defiance. Breaking rank, model Ayesha Tan-Jones flashed their palms to the camera, revealing the hastily scrawled message “mental health is not fashion” to cameras and on-lookers. Going on to post a message on Instagram expressing solidarity with those struggling with their mental health, Tan-Jones proves that sometimes ethics come before aesthetics.