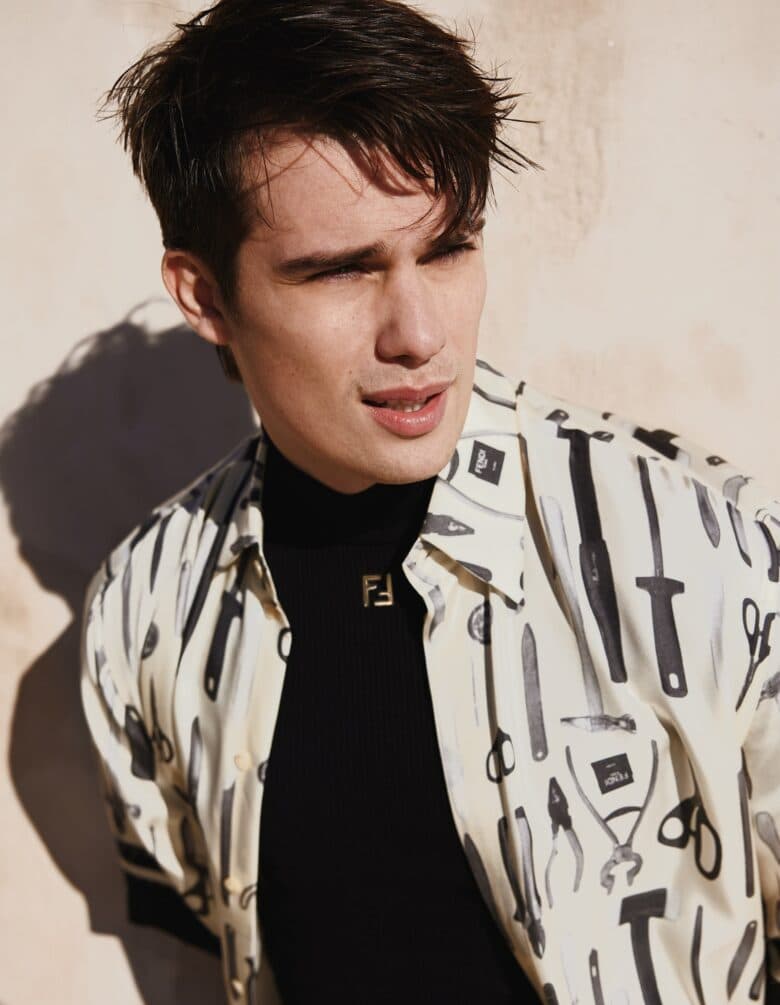

Natasha Stagg talks fashion, authenticity and being “famous for being famous”

Sure, we’ve barely processed the mess that was 2016 but, as we sit at the precipice of a new decade, it’s time to consider the ten years that have just been. Looking out towards the wider world, the 2010s witnessed the birth of influencer culture, the rise of branded content and the erosion of any barriers between our “real” and IRL selves. Whilst we not-so-slowly merge with our phones, the political landscape around us is becoming increasingly volatile. The old certainties of left vs right are being stripped away as our beliefs become multifaceted, multilayered and, to be frank, pretty confusing.

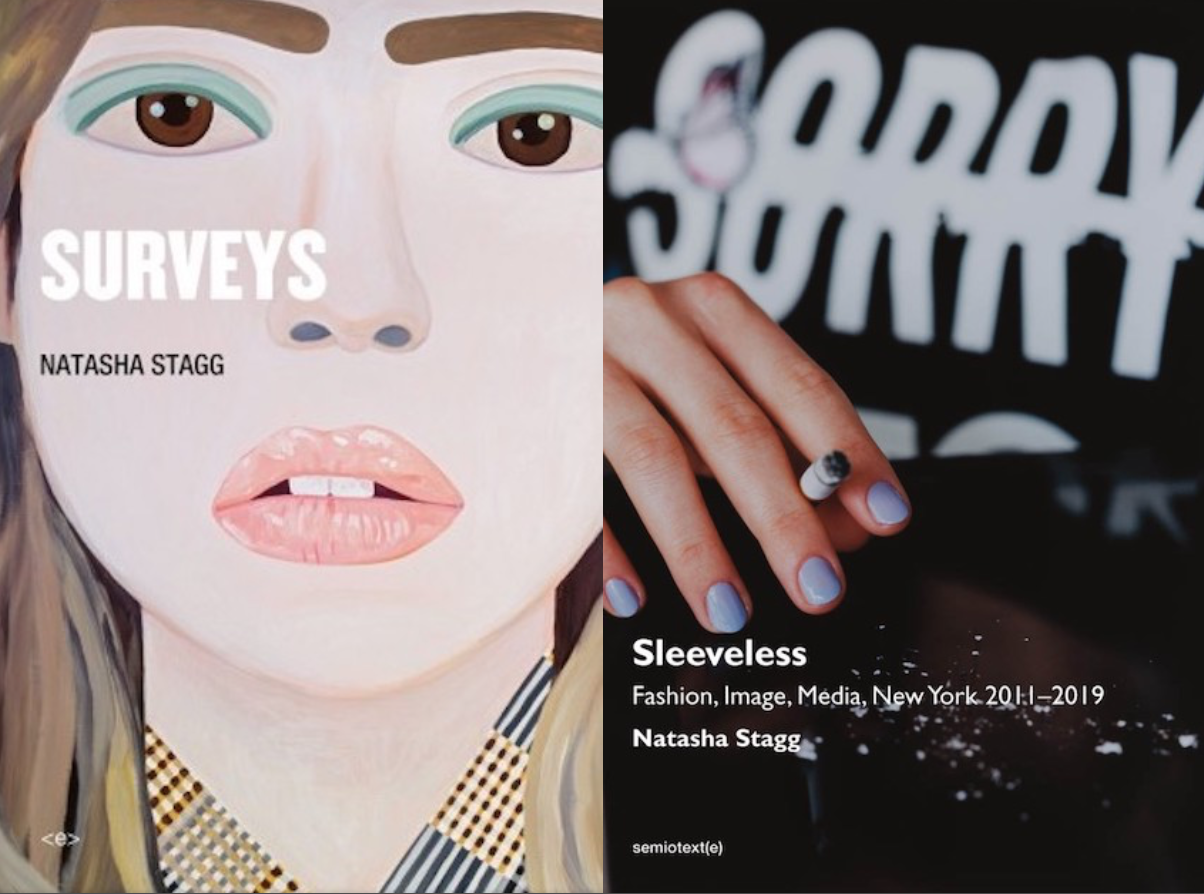

A tangle of hot takes contributes to making it so hard to decode whatever the hell is happening and this is what makes Natasha Stagg’s writing so necessary. As a fashion journalist and former editor of V Magazine, she has always been attuned to the narratives we tell about ourselves; whether that be through clothes, words, or how we document ourselves online. The sharp social commentary of 2016 novel Surveys, about the pursuit of celebrity, and essay collection Sleeveless, about life in NYC, provide a refreshing sense of objectivity.

With a sense of disaffected detachment, she’s been one of the few individuals to give some kind of shape to the developments of the past few years — which is why HUNGER decided to sit down with her to discuss the contemporary state of fashion, authenticity and fame.

You’ve acted as something of a chronicler of our times, particularly in your most recent work, Sleeveless. What are your big “takeaways” from the 10s as we edge towards the 20s?

It’s been a rough decade. I’ve been mostly disappointed but at times very inspired. And in love!

Your first novel, Surveys, is an examination of, in part at least, the condition of being “famous for being famous.” You’ve previously said that this is a more “authentic” form of celebrity — would you be able to expand on what you mean by this?

Authentic is a funny word, especially now, in the age of deep fakes and monetizable brand personas. But what I meant was that, when this concept first arrived, it seemed to be controversial for illogical reasons: if someone is famous, it is because of a combination of right times and right places, nepotism, the zeitgeist, and of course charisma (or a perfectly placed lack thereof). Therefore, being famous for being famous really just means being famous.

Having engaged in this examination of influencer culture in your work, what are your thoughts on the rise of the writer-influencer? Where is the line we draw between the Caroline Calloways of this world and the Tavi Gevinsons of this world — and why is one a writer and editor and the other an influencer who wants to be a writer?

It’s a great time to be a writer, isn’t it? It’s hard to separate persona, work, and brand, and so styles like auto fiction and personal essay have seen new experimental territories recently. It’s still a matter of taste when these writer-influencers are defined as such, or when someone is classified as a wannabe writer who happens to be doing a lot of writing.

There are literary agencies now for this kind of “digital first talent” — how do you see the role of the writer evolving?

I see the content of a life becoming more marketable than the craft of one’s work, which has always been the case for someone, whether it be actors at some point, models at another, and actually, a long time ago, writers, too. It’s a little different now, having to deal with a shorter news cycle and precarious or dubious sponsorship, but we are all still responsible for how known and paid a public creative is.

We’re in the midst of an age of aggressive cultural recycling, to what degree would you say this has always been the case?

It seems like this has been happening forever.

You’ve previously discussed the fact that there are multiple selves that we navigate, depending on whether we’re URL or IRL and then, within that, depending on what spaces we are occupying. Do you think this idea of having multitudes of selves is only going to become more pronounced?

It seems to be far more easily discussed, now, in casual conversation. For example, I was just at a work meeting, and afterwards, a coworker said something about gaining a new understanding of the word “avatar.” The joke was that we could be the avatars of our online selves, not vice versa. It seems like this type of discussion was exclusive to The Matrix superfans back when I was in high school, and now it’s common discourse.

As we start thinking more about the cultural and social context art is created in, do you think that there is ever a way for art to make a positive social contribution or do you think it’s more useful to disengage with this wider discourse to a degree?

It does seem like everyone is trying their best, sometimes. I have so many friends who are genuinely concerned about the work they are making and how it might accidentally make a bad impact. We’re stuck in a lot of overlapping systems that make it so we hardly have a choice but to live comfortably unaware of certain issues. I think it might be best to not overthink it at times.

Fashion writing is often seen as propping up the industry rather than intervening in a useful or interesting way. Is this fair? What do you think are the potentialities of fashion journalism beyond that (mis)perception?

I have to stand up for fashion because I love it. It’s the industry that takes itself too seriously and the one that is at the same time completely self aware. It knows it’s a commercial endeavor at its core, and yet it can’t help but explore the intricacies and aesthetics of culture, every day, forever.

Sleeveless: Fashion, Image, Media, New York 2011–2019 is out now via Semiotext(e)/ Native Agents.