Rave culture is dying — This is what the future of clubbing looks like…

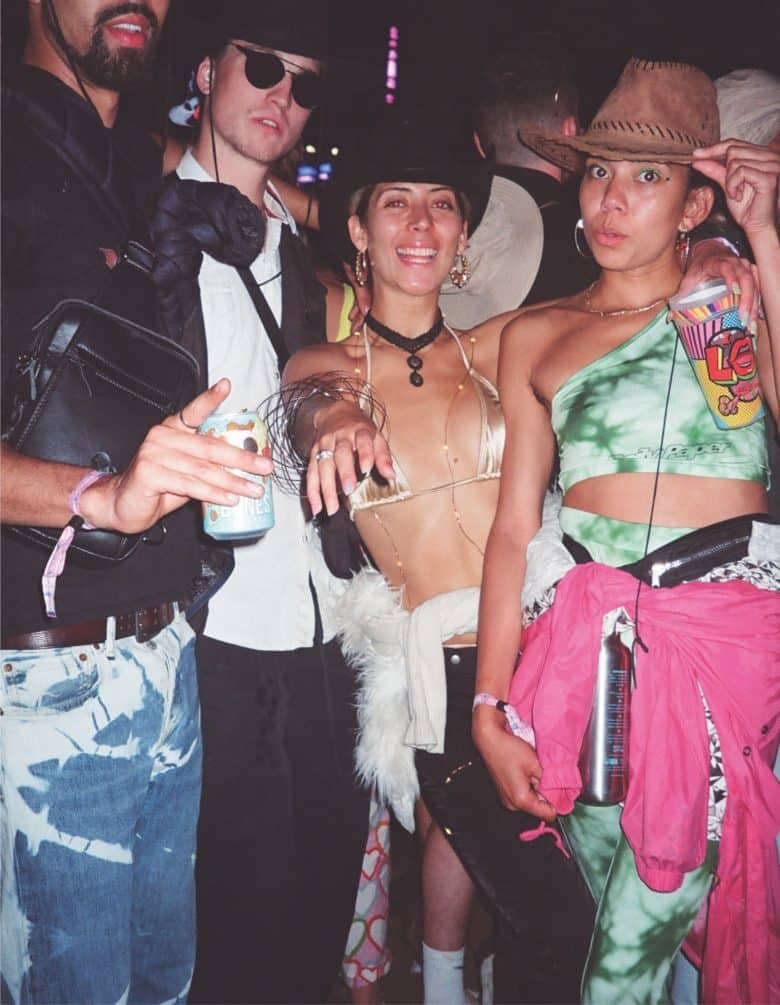

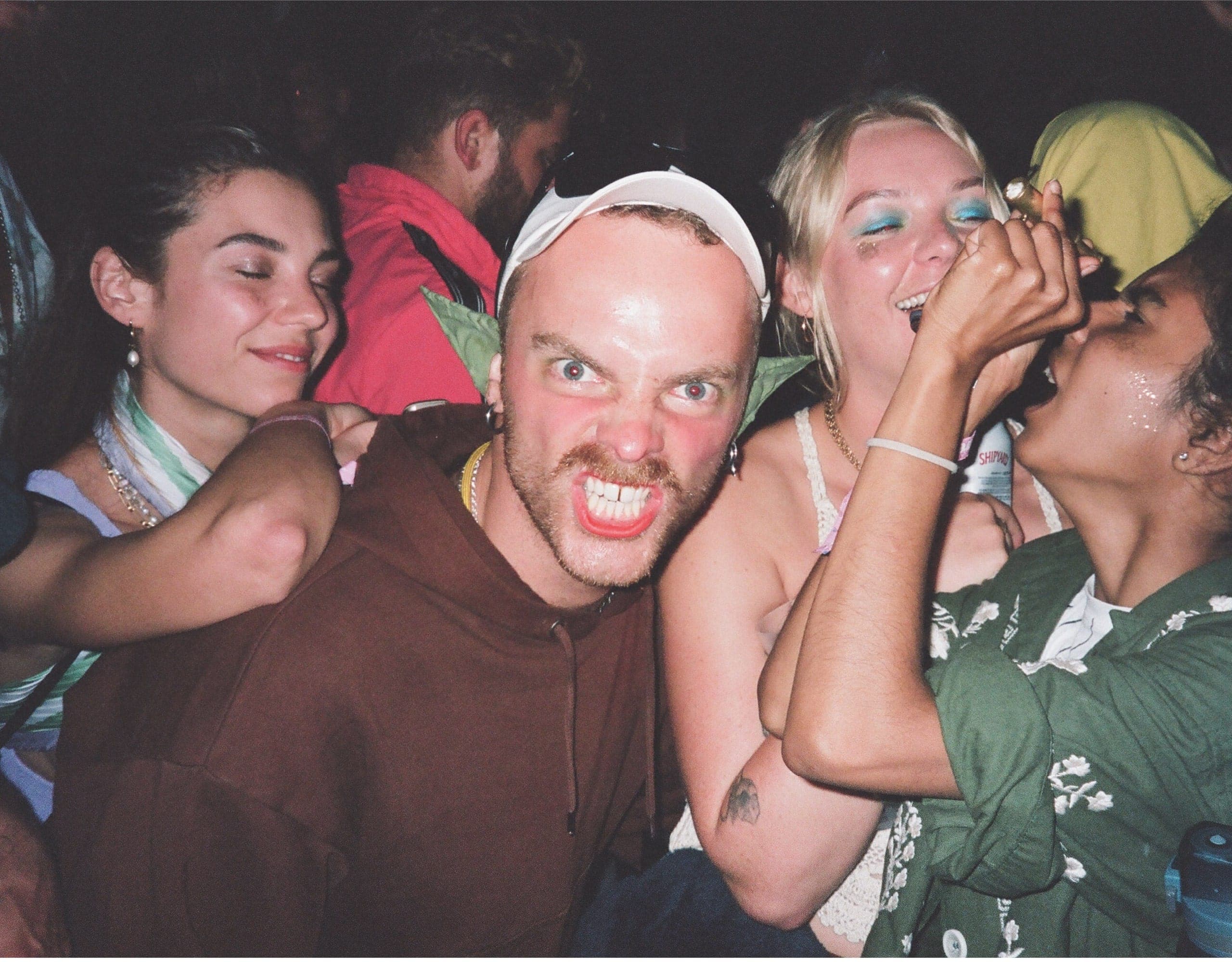

It’s 2am on a Friday and the night’s just getting started. Everyone is fixated, eyes bulging and ears throbbing – living entirely for the early hours without a second thought about getting to a desk for 9am. To the untrained ear, the music is near-deafening, never relenting long enough to yell in your friend’s ear, “DO YOU WANT ANOTHER DRINK?” It’s perpetual. But that’s part of the fun, apparently.

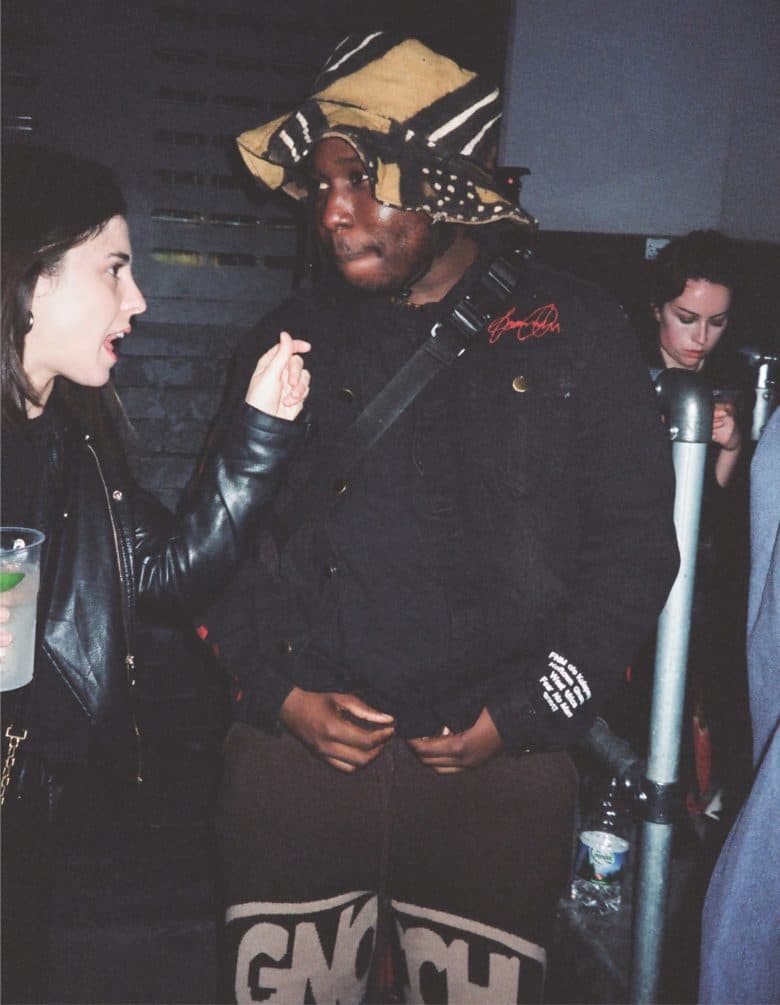

Do I personally enjoy the music? Not really. Are the drinks expensive? Of course. Was I borderline terrified trying to find the well-hidden, soundproofed venue located between the ominous building of a Russian bathhouse and mounds of scrap metal in east London? Definitely. But this is all part of researching what hedonism means in this post-pandemic era. Walking past the venue’s empty red sofas, most likely used during the more sexually expressive nights held here at the weekend – echoing the laissez-faire attitude of clubs like Berlin’s Berghain – I arrive at the smoking area and find this is where people are able to disclose what they’re doing here and discover more about their total disregard for the fact it’s a weeknight.

“I’ve always wanted to come to Fold,” says a young woman with a fresh buzzcut about the place that’s becoming the most talked about location in London. “I think people look for nights that are closer to who they are now. Not so much just for the sake of going out or getting fucked up.”

That’s quite a disappointing sentiment to hear when you’re looking to write about how everyone’s getting on it the whole time and living for the weekend. But as I make my way through the clouds of smoke, searching for one person who will tell me they’ve ramped up their Class A usage in search of absolute liberation of the mind after Covid’s restrictions made indulgence in any form of clubbing activity impossible, I slowly realise that no one here is ‘fucked up’.

So what gives? Since the pandemic began there have been stories of secret raves and rumours that the old-school staple is back and better than ever. In January 2021, the BBC reported that 300 people attended a rave at the railway arches in Hackney, with £15,000 worth of fines dished out to the wide-eyed attendees. During the shit show of 2020, the term “rave revival” started being bandied about – from London to Manchester, news of thousands of pounds’ worth of fines being handed out to groups of people in warehouses, forests and open fields was lapped up by anyone who used the word “covidiots”. To most people, the pure quantity of reports made it seem like raves were back, and with them, the desire for hedonism. So with restrictions lifted, people were diving back into freedom headfirst – into all sorts of drugs and raves akin to those held in the 1980s and 1990s – trying to make up for lost time, right? Wrong.

The news might want you to believe that the rave revival was underway, but that overlooks how we’ve changed as a society since the days of illegal all-nighters, how the nature of clubbing has evolved, and what hedonism looks like now. Graeme Park, one of the Haçienda’s leading DJs in the 1980s, tells me that raves now are very different from what they were. “Back then, when acid house came along, it happened to coincide with ecstasy appearing as well. Everyone was just on E, it was great,” he says. “[Now] people in their twenties just seem so full of enthusiasm for life. When I do the Warehouse Project [in Manchester], for example, it’s a great vibe, but at the Haçienda you could see that the majority of the crowd had dropped a pill. At WHP I can just tell that not everyone there is taking drugs. Clubs will always be there, but every generation has got their different drug or vibe that they latch onto.”

The heyday of rave culture was when the stories of real clubbing began. Park tells me that during one New Year’s Eve at the Haçienda someone set fireworks off on the dancefloor. Another night, a whole fairground setting was created where attendees could drive bumper cars and ride a Ferris wheel – there were even burger vans. But by the end of the night, the food vendors were furious as they hadn’t made a penny. Later they discovered it was because people had wanted copious amounts of water and chewing gum, not cheeseburgers. There were teachers dancing next to footballers, next to criminals, next to businesspeople, next to the unemployed. It was totally hedonistic, from head to toe, and that was why the club eventually collapsed in on itself.

Fast forward to 2022, and there are two ways the pandemic may have tilted the course of hedonism. On the one hand, people now have the opportunity to reconnect with the nights they actually enjoy, listen to the music they want to listen to, and find their own hedonism within spaces that feel familiar to them. On the other hand, the pandemic allowed time for reflection on the effects of drugs, and spending days deep in a comedown is no longer appealing.

“I think it’s natural that young people want to go clubbing, to feel loved up. They want to have a good time,” says John O’Reilly, a psychotherapist who has worked in the field of substance abuse for more than a decade. “But the pandemic would have forced them into really confronting that and realising there are other ways to feel good that aren’t so costly in terms of their pockets or their health.”

Harry, a 24-year-old model living in London, is one of the people for whom nights out have become an opportunity to connect with what he enjoys on a personal level. “When restrictions eased, I felt there was a cautiousness around clubbing. Coming to London, the nights have become more hedonistic, and there’s more of an appetite for that,” he tells me over the phone. “Non-queer friends are getting into a lot of hedonistic nights, like sex parties. I know a lot of people are exploring open relationships and getting into polyamory. That’s different to rave culture, but I think it all feeds into this rejection and moving into something different.

“In my house, there are sex parties and day parties – there are always things going on. Hedonism to me means escaping a kind of mundanity, norms, binaries and routine – going into a different consciousness.”

And that, in many ways, is not something that has changed over the years. Indulging in clubbing, drugs and raving is still a way of rupturing the humdrum with 12 to 24 hours of debauchery. And as one person who attends various illegal nights tells me anonymously, that culture is still alive, but it’s dwindling as the raves go by.

“Probably the most in-my-face thing I’ve seen is full-on sex,” he says, going on to explain that people only hear about these nights via Telegram groups or pirate radio stations. “It’s generally people who just enjoy music. I’ll be honest, raves are beginning to disappear because a lot of clubs are holding rave-type events. A lot of people that followed raves are going to gay clubs and clubs that you’ll see advertised in telephone boxes. You’ll find that these are very rave-like. These illegal raves… there’s not a lot of them. Especially since the pandemic, large scales of people are very easily clocked now.”

Yet another blow to the angle of this piece… It’s not a good sign that even someone who moves closely in these circles says that raves are on their way out. But at this point, it’s hard to ignore the truth in front of our eyes. Rave culture may be dying, but only in the sense of what we knew. Thousands of people in a field being herded by the police will, most likely, no longer be a staple of the culture in the UK. Instead, hedonists get their fix in the form of music, and maybe drugs, from smaller nights that not only offer similar experiences but cater more to individual needs.

Take nights like Tech Couture, Ryan Lanji’s Hungama, Adonis and Unfold in London and Rat Party in Leeds, as well as venues like Manchester’s White Hotel, as prime examples of rave culture being filtered into nights that tap into individual preferences. But beyond club nights, there has also been a boom in interest for family raves, such as the 2-4 Hour Party People event, day raves, gigs reclaiming their rightful place as the beacon of music outings, and sober nights out.

“When I DJ’d before the pandemic, I used to drink a lot,” says Harry Gay, one of the founders of Queer House Party, which began its Zoom club nights during the pandemic. “I no longer drink. That’s another thing that really helps. There’s a big chunk of us who have gone sober just because of the nature of the work.” Be it queer events, sex parties or whatever, clubbing is now a personalised experience for people who know what they want out of it, both in front of and behind the decks.

And that’s exactly what Bessie and Oli, the founders of Tech Couture, tell me. “I don’t feel like people have gone full force into getting really wasted and being super- hedonistic,” Bessie says. The pair started their “sexy techno” night three years ago and wanted to prove that the scene wasn’t just a male-dominated environment that takes itself too seriously. “When you look at places like Berlin, there’s a very hedonistic scene. But something that we love about those worlds is that people have a deep respect for the music.” But the reason Tech Couture is taking off as an open-for-all techno night with a twist is because it’s built with the music lover firmly in mind. “I think the thing with the UK is that there is that get- fucked-up culture,” Bessie continues, “but we want to show that it’s not always about that. We want people to lose themselves and express themselves. It’s about the music, but it’s really about bringing people together.”

And that’s the future. Raving – or this evolution of raving – isn’t exclusive to those who know where to look anymore. It’s inside venues around the country, being experienced by people who would never dare (or can’t be bothered) to trek 15 miles outside the capital to drop a pill and dance until the sun comes up for a second time. But beyond that, behaviours have changed along with rave spaces. As O’Reilly explains, attitudes have shifted, as well as our priorities and areas of interest that are capable of giving us the satisfaction and pleasure that hedonistic environments like raves once did. “People are experimenting with their sex and sexuality,” he says. “You may have seen the rise of sexually transmitted diseases during the pandemic. But that tells you that people are, to put it crudely, fucking more and raving less.”

Whether it’s sexual desire or because younger generations are more aware of the effects of drugs now, or because the pandemic has made us want to experience moments properly, our memories unimpeded by hangxiety and drug-induced brain fog, hedonism is now characterised by personal desires. This has paved the way for nights that represent individual aspirations to escape, just for a few hours, in a way that unifies different communities while keeping the meaning of raving at its heart.