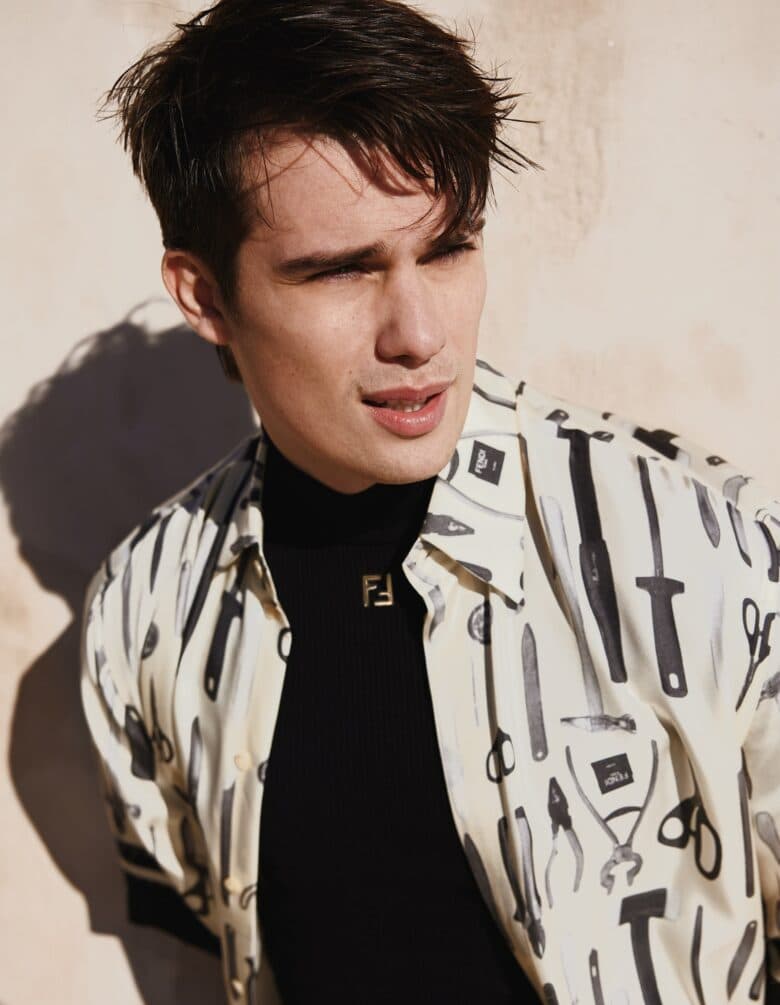

Listen Up Issue: River Gallo on being a voice of change for the intersex community

“What’s the deal with that name? I know your mama didn’t name you Ponyboi.”

“No, my daddy did. When I was little I always hated going to the doctor’s. And I loved ponies. So whenever I went with my dad, he said if I was a good boy, he’d get me a pony.”

This exchange between Ponyboi, played by River, and Bruce, literally the man of Ponyboi’s dreams, hints at a history shared by almost two percent of the world’s population: frequent, unsettling visits to doctors’ offices. River, who is intersex like their character Ponyboi, is now turning the short into a feature-length film, with co-director Sadé Clacken Joseph.

“I remember being seen by doctors throughout my whole childhood. I was always having my genitals checked, but I thought it was a normal thing. Looking back on it actually it’s like, ‘No – it was far more often than other children.’ [Appointments] were more frequent but also veiled with mystery, not knowing exactly why I was there,” River explains. “Then when I finally found out about my body, it became a secret. I couldn’t talk about what happened at the doctor’s office. There’s a reason why a lot of intersex people have anxiety and trauma about going to the doctor in adulthood. That doctor’s office smell, I still smell it sometimes. That off-brand cleaning detergent smell transports me to this time where it felt like the world was a secret, where I couldn’t trust anybody. When I found out, it felt like a major betrayal on my parents’ and doctors’ part. These figures that, when you’re a child, are larger than life and meant to protect you, it felt like they’d been lying to me my whole life. Secrets kill people, emotionally.”

Intersex – people born with biological sex characteristics that don’t fit the binary definition of male or female – is a wide spectrum of variations. It’s also common. It covers everything from hormone levels and chromosome patterns to testicles and ovaries. None of these necessarily need fixing.

Advocates like River, as well as organisations including the United Nations, are trying to ban surgeries being used by doctors to define young people’s genders. They believe that intersex people should simply be free to make their own decisions about whether or not to have. “I found out I was intersex when I was 12,” River says. “My parents brought me to the doctor’s office and told me that I was born without testicles, and that I’d have to start going through testosterone treatment.”

Campaigners want more information and education for those born intersex, with any sex assignment surgeries held off until the individual can make their own decision. “When the time came to become an adult it was an intervention by doctors, and what I now think was a nonconsensual decision, especially a surgery. I still take testosterone now, I think I would have taken it regardless. But to have a surgery that was just kind of forced on me is shocking. I was 16 when I had the surgery. I was pulled out of school. I had to keep it a secret. I told my friends I’d pulled a muscle on my groin from being on a treadmill or something. It was absurd.” For River, the pattern of secrecy was already set. “I’ve talked to other intersex people about it. There’s this idea that doctors place on us that we’re so rare, or special, that no one else is like us. It almost forces us to be secretive about it. The conditions and the variations we’re born with deal with the most intimate parts of our bodies. Social conditioning dictates that you don’t talk about having a prosthetic testicle implant at 16.

“A lot of what we’re fighting for is to talk to children about it from an early age. Why can’t you tell them the truth about their bodies from the beginning? What’s the alternative? The alternative is keeping us secret and then always structuring our identities, our existence, and our bodies in a framework of shame.” For River’s parents, questioning doctors’ treatments wasn’t really an option. “My parents were immigrants from El Salvador. They literally grew up in a dirt-floor shack. For them to make it to New York from that kind of poverty, so I could be born in a hospital, was such an incredible feat. They listened to my doctors with absolute obedience. English was their second language. They had no other context for standing up to doctors or asking for more information. The information wasn’t even provided for them, that intersex even existed, that there was a community. So I didn’t know intersex was a word until two years ago. I had already started identifying as queer, but it wasn’t until I went to film school and started making Ponyboi that I wanted to include more of the narrative of growing up with this variation in my body.

“I learned the variation I was born with is part of a larger term called intersex. And for the first time I realised there were other people like me that were talking about their bodies. This is about human rights violations, and there are activists, and a community of people who have shared all these experiences. It felt, for the first time, that it wasn’t just about my sexuality – that I was attracted to men. Finally, all those things integrated into this larger picture of who I was. And then I realised that was missing my whole life. I knew I was different, and I knew my body was different. But I hadn’t heard any stories like mine, so I felt like a unicorn or something. We want everything to be nice and neat. That there are only these two bodies that you can be. It’s clean, understandable, digestible and palatable. But the truth is it’s not. It’s not.”

River credits the work of the trans community for paving the way for the intersex community. “Now intersex people feel the courage to step into the light, because of the trans liberation movement in the last decade. They’ve fought for visibility and rights.

“This conversation about being intersex is now this interesting parallel existence. On the one hand, trans people are fighting for their surgeries, for their hormone treatments, to transition. On the other, intersex people are fighting for our right to decide on the surgeries and medications that are being forced on us.”

The queer community is, even now, still dealing with people’s belief that sexuality is a lifestyle choice rather than something they’re born with. So how do perceptions of intersex people fit into this – if at all?

“There are intersex people who are not queer. They don’t want to be part of the alphabet. They want to look at it entirely as a medical situation, and want to correct their bodies to the heteronormative paradigm. I have intersex friends who are heterosexual and cis-gendered. But to me, I think it’s missing the point when one wants to look at it completely in medicalised terms. There are some people that choose to be cis-gendered, and it works out for them completely, but for intersex people who are non-binary, for intersex people who are trans or queer, it is a human rights violation. Because other people are literally taking control and removing agency over decisions about our bodies that should be our own.

“The sheer loneliness and isolation that one feels growing up intersex without anybody to talk to is a form of emotional torture – for doctors to withhold that information for the sake of potentially disrupting some sort of gender binary they’re crafting.

“There are some doctors who are shifting the paradigm now, and are more information-focused and aware of the human rights issues involved in it. Doctors in medical schools are reaching out to the groups I advocate with, because this starts in medical school.”

It’s important that advocates like River are finally being heard by governments and the medical industry, but the fight is far from over: “I’m fighting for body autonomy and identity autonomy. At the end of the day it’s an intersectional issue because it goes into women’s rights, abortion rights, it goes into socio-economic rights. Who has the most access, mobility and education to be able to define their gender and identity the way they want? We’re fighting specifically to delay surgery. In some cases surgery is necessary but for the vast majority it’s not. So there’s no harm in delaying it. You could still have it [later].”

River says that the solution lies in talking to intersex children about their bodies as soon as they’re old enough to be able to understand the language. “Children aren’t born with shame. We teach them shame. They just have bodies, and they just understand how their bodies are in that moment.

I think it’s an opportunity for parents to turn something that would be an embarrassing conversation into something that would be empowering. To be a leader, to be an actual parent, it’s difficult, but let’s not leave this to the medical industry.”

River Gallo is one of our cover stars for HUNGER issue 17, Listen Up, available here.