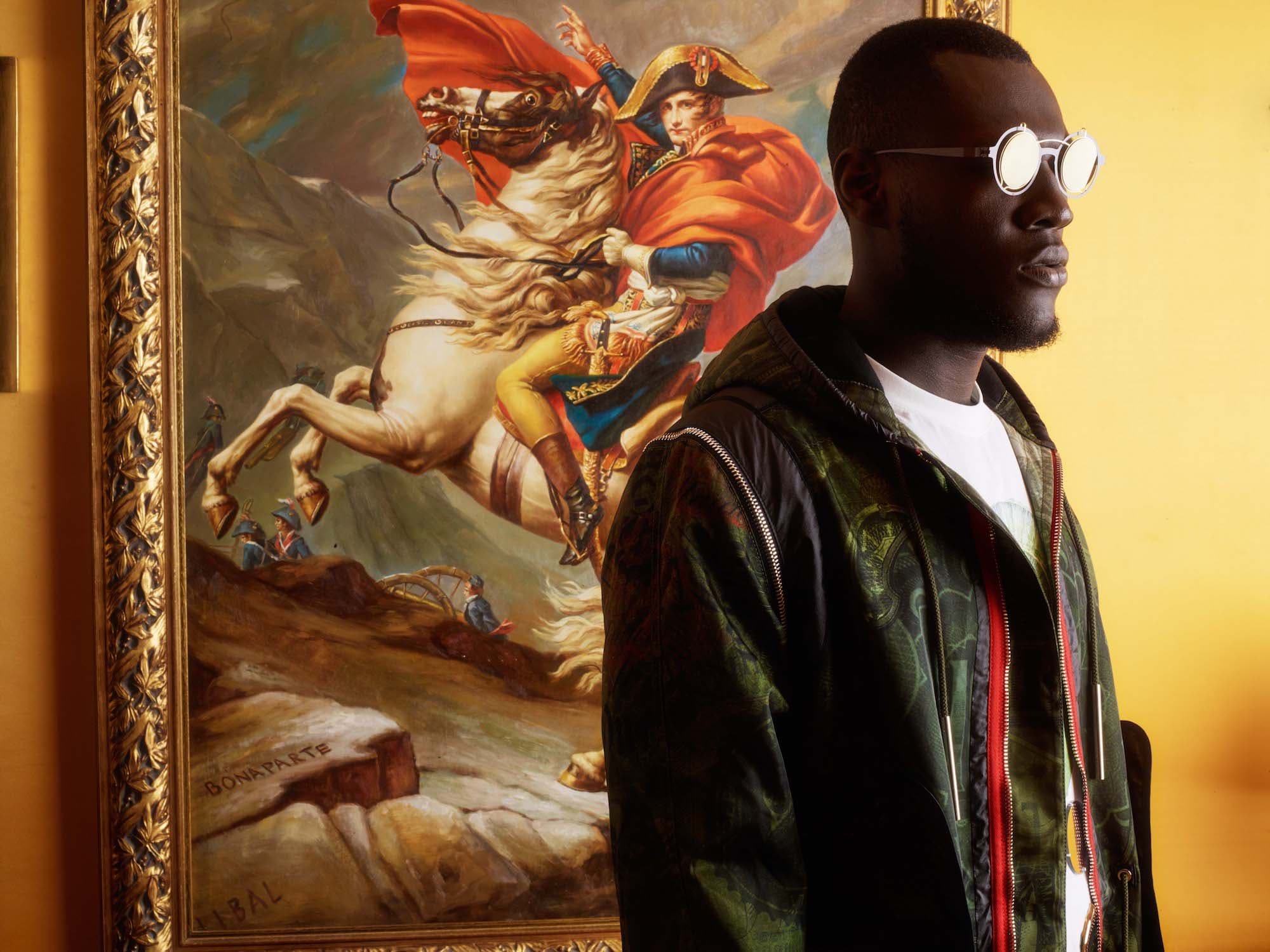

Stormzy on how he’s beaten the odds and paving the way for young black kings

The following feature is taken from HUNGER 12, the Stand for Something issue.

“You can tell they think I’m not supposed to be here.” Michael Omari, better known as Stormzy, and I are having lunch in an Italian restaurant; he’s answering my question about what his neighbours think that he does for a living. He’s referring to his house in Fulham, where he’s recently moved, and for Stormzy, it’s just par for the course. “I’m gonna live where I live,” he shrugs. “I’m gonna have my hood up, wear all black and I’m gonna be in a first class lounge, or in this mad restaurant, or in this posh hotel and be like, ‘Oh, you didn’t think young black people could be here?’” As if to prove his point, within a few days of this conversation, his face is plastered across the front pages, after the MET police kick down his door, mistaking him for a burglar in his own house – the details of which he tweeted to his 551k followers.

He’s listing more examples of everyday racism with animated stoicism. “I remember when I went to buy my manager a Rolex for his birthday,” he says. “Usually when you walk in these high-end places, they’ll offer you a drink, take your coat, offer you a seat. We didn’t get none of that. I asked, he told me the price, and I did it like, ‘Oh, you didn’t think young black men are supposed to have this money, did you?’”

The memory is delivered with a smile, and as he gets glances from nearby white-haired diners around us, it’s clear that taking ownership by becoming more comfortable with his visibility is all part of Stormzy’s ascent to greatness. One of the biggest of grime’s new world order, Stormzy has become the figurehead for a new generation of grime MCs. He’s currently enjoying a Top 10 single, a sold-out tour, and his upcoming album is expected to go into the Top 5.

But it wasn’t until the success of “Know Me From” that the 23-year-old British-Ghanaian really captured public attention, giving the scene a handful of quotables (“Peng tings on my WhatsApp and my iPhone too/The brown skinned girls and the white ones too”). His next single “Shut Up” became the most viewed UK freestyle ever. And it was Kanye’s now infamous Brits moment in 2015, when he brought onstage a slew of grime MCs to perform with him, including Stormzy, that contributed to the success of “Shut Up”. In two years, Stormzy made the acclaimed BBC sound of 2015 list, won two MOBOs, grew a beard and put grime’s mainstream hiatus back into overdrive with a simple question asked on “Know Me From”: “If grime’s dead then how am I here?”

Growing up in Thornton Heath in South London with his mum, brother and two sisters, Stormzy tells me he didn’t come from a particularly musical household, though he likes music. “My mum played some highlife in the house, and my sister would fall asleep to slow jams on Choice FM,” he says between picking at lamb chops. Grime’s top MC was nearly a top engineer: he was picked out of thousands nationally for a prestigious project engineering apprenticeship and he was a self-proclaimed ‘good boy’ getting 6 A grades at GCSE, before getting expelled from college for what he calls “a string of offences”.

He was taken across the country, to Scotland, then to Southampton for his apprenticeship, then back to his home in south London. As a result, his story is less one of urgently, desperately spitting bars on the playground but of taking a breath, drawing from experience and normalising black excellence. The album title “Gang Signs And Prayer” is a nod to that and his youth spent in a Pentecostal church, which taught him the power of prayer, and his music is the culmination of meditative observations, now delivered to 140 beats per minute. It’s a chapter of his life he mentions on “Blinded By Your Grace Part Two”, a journey back to church, which sees him singing alongside the Harlem choir in New York, in a euphoric swell of supplication and introspection as he sings, “You came and saved me”.

Coming up, Stormzy was inspired by Skepta and Wiley, but for him, it was seeing himself on platforms like Channel U (now Channel AKA, a Sky music channel catering to urban music, specifically grime) that inspired him to study the greats and try and emulate them with his then crew Clifton Bloodline, who, he says, were rapping about “life’s fuckeries” on the estate.

He’s laughing and shaking his head at himself as he retells the story of the birth his MC name. “I was in Year 8 and everyone was trying to find their nicknames. You had ‘Younger Killer’ and ‘Angerman’ and ‘Tiny Verbz’ and all these silly names and you just tried to find the wackiest one. I thought Stormzy sounded pretty cool.”

“I grew up on Channel U, so I wasn’t running in every time a black person came on TV, because I grew up on that, just seeing people that looked like me. I saw Chip coming through, Griminal, Narstie Crew. You couldn’t even believe that man from the endz was on telly! And every now and again you’d have a man from your bits and you might know him and it was amazing.” In a scene jam-packed with caricatures, he is, of course, as his album title suggests, an artist with fascinating duality. To read the lyrics of “Big For Your Boots “ (“I don’t care who you know from my block/You’re not Al Capone, you’ll get boxed”) you might believe the intimidation, but it’s delivered in comical overtones, jumping and grinning onstage in live performances. From getting his mum in the video of “Know Me From” to rapping about his penchant for hot chocolate and paninis on “Shut Up”, he is almost constantly challenging people to challenge him. He is much like Dizzee who came before him in that his manner in person is as it is on his record – sharp, funny, and distinctly likeable – but in a climate more inviting, with more platforms to champion him thanks to the groundwork done by the older generation.

Visibility has been crucial to Stormzy’s development as an artist, and much of that is thanks to being keenly aware of his physical form. “Well, as you can see, I’m 6”5.” he laughs, “And it doesn’t help either that I got a deep voice. All these things can be intimidating to the average person. So I always knew I would face that struggle. I try and smile a lot, but you don’t always feel like smiling, do you?”

Carrying oneself differently is part of the street survival guide for boys used to getting stop and searched regularly. “When I was growing up in Thornton Heath, from about 13 all the way up to 18 I got searched every day!” he says. “I’m talking all the time, to the point that I was like, ‘Yeah, yeah, okay, hurry up I need to go.”

I ask him when that stopped and he shrugs, “When I stopped walking around on the streets! But now I have a nice car, so I get pulled over instead.” The banality of the MET’s imprint on people’s lives is nothing new for many MCs who have grown up similarly to Stormzy, and grime music has never been divorced from the politics of being black. It’s something he doesn’t shy away from talking about, and he’s pointed when he discusses the experience of being a working-class young black man in Britain. The lead single, “Big For Your Boots”, was released with a video that tried to represent British identity and values on his own terms, and that’s what this album is about. The video shows an array of people, from the first ladies of the scene including Julie Adenuga, Ray BLK and 1Xtra’s Sian Anderson to two Sikhs bopping to a beat.

“I was trying to reflect a very British video but not in the normal way that an MC would show Britain, shooting their life on an estate,” he says. “We had the idea of these juxtapositions of putting them in places they wouldn’t normally be. Like, man dem that are from the endz don’t go to the pub, so let’s put them in there.” Stormzy’s view of Britain is a 6’5 one, from a perspective most people don’t experience first hand. Taking in the ignored details and slowing down reality to process it in his own way is done quickfire, from shouting out Wiley and Dizzee on his first single, to singing his lungs out to Adele in the O2.

I talk to him about his own duality and we launch into a conversation about his favourite book, “Noughts and Crosses” by Malorie Blackman and how it led to him to consider being an English teacher; his political heroes (Obama and Martin Luther) and the Louis Theroux t-shirt he’s wearing. “Louis is so sick!” he says. “He gets to the nitty-gritty in the most intelligent way, I think that’s why I like him so much.” He doesn’t recognise his own parallel when he makes the observation, and it’s a sweet modesty that he doesn’t think of it.

Stormzy is a success story for the independent model, having self released everything up to this point without a label and with a small team of six, following in the footsteps of MCs like JME. He is living proof of what happens when you take an uncompromising approach when speaking to your fanbase. “I’ve never seen a major label know what to do with black artists.”

His is a story that grime can make it, that DIY culture can thrive when there isn’t resource or infrastructure readily available. His album is testament to the power of A&Ring your own music on your own terms. Feature credits on his album include Kehlani, MNEK, Wretch 32 and J Hus. He’s taking this further with the creation of his #MERKY record label. He’s self-deprecating when I ask him about signing artists before he’s even had his debut album out and he smiles, “Well, yeah, that’s why I have to wait a while to sign people, because what do I know?”

Of course, he knows more than he’s letting on, and his observation, of labels not understanding underground scenes and not knowing what to do with black artists, makes his position political by its very existence. British police and politics have been continually distant from underground black music scenes, and particularly grime throughout the mid 2000s, which saw symbols of urban menace like hoodies and tracksuits increasingly demonised. (Hoodies were famously banned in Kent’s Bluewater Shopping centre in 2005). Now, when you see artists like Stormzy appearing on front covers in full tracksuits, it takes on a renewed politics. He talks about a story last year that gained huge momentum after he tweeted about it – a London nightclub, DSTRKT, turning away women who were deemed too “dark-skinned” to enter. It gets a mentions on the album on “First Things First” (“Fuck DSTRKT”) atop clipped basslines and eerie productions as he spits, “If it wasn’t me you wouldn’t let my ni**as in the club”.

“I thought, if that would have been my sister, I would be ready to jump in my whip,” he says. “I would be on Twitter telling everyone, ‘Fuck this club! We need to shut it down!’ So what, do I have to wait until it happens to me, or my sister until I say something? Fuck that.”

It’s perhaps testament to his independence that he can react quickly to news without fear of major label or management recrimination, and he’s smiling as I mention this. “It’s bigger than that,” he says. “Before, the Prime Minister says something and you can sit in your house and say to your mum, ‘That’s wrong, he’s a dickhead’ and that’s the end of that. Now, you go on Snapchat or Twitter and say ‘No, that’s fucking wrong,’ and it might lead to a protest, so there’s this whole big revolution that’s going on. Now everyone has a voice.”

Stormzy’s voice is about him learning, pushing back, and giving us a perspective of British life through the lens of resistance, political visibility (whether intended or not) and a young person in 2017. The album is proof of his duality, debunking the idea of one-dimensional views of abrasive black masculinity, and punctuating it with vulnerability, anger, resistance, pain and pleasure. His debut record hits you over and over again to make a simple point: black identity is multifaceted – and he is on track to be astronomically successful. The harder edges on Gang Signs And Prayer come on songs like “Bad Boys” referencing his younger braggadocio, placed alongside his soft moments, singing whispered love songs on “Velvet”. These stand-out moments really say it all about who he is right now. On “Lay Me Bare”, a torrent of raw, angry emotion that channels Eminem circa 2001, he talks about seeing his dad after years of absence and you hear him spitting venom into the ether (“When you hear this I hope you feel ashamed”).

On “First Things First”, he opens up about his depression, a nod to the lack of infrastructure and resources available to him and people like him, while on “Cold”, he takes us into moments of humble posturing, stating “I’m just a young black man living off grime”. Later in the same verse is a rallying cry, “All my young black Kings/Rise up this is your year”.

He’s mobilising a generation to follow where he leads, just like he’s followed the footsteps that’s come before him. For Stormzy, it’s not just about the music, it’s also about challenging black narratives. Unlike the Met Police, he seems to know precisely which doors to kick down.

“There’s gonna be way more successful young black people coming through,” he says. “So I’m just here saying, ‘Look you better get ready because there’s bare of us, hundreds of us, coming and we look like this and we dress like this and we talk like this and we’re here.”