The artist behind inflatable celebrity Pandemonia weighs in on his thoughts and fears about the digital world

I’m chatting to Pandemonia, or rather the person behind Pandemonia – the inflatable pop art persona that rose to fame by gatecrashing fashion week shows more than 10 years ago, and was quickly embraced by the sartorial and celebrity worlds soon after. We’ve decided to go old school for the interview and talk on the phone, which might seem a little unexpected considering we’re discussing the use of VR headsets, the perils of social media and life as an avatar – all for a magazine issue that’s dedicated to the metaverse.

But we have our reasons. Despite having worked with everyone from Camper to Jean Paul Gautier and having graced the pages of high-fashion magazines across the globe, the artist behind Pandemonia has managed to remain anonymous all these years. So a video call is out of the question unless he puts in the hours it takes to don the full latex mask, sunglasses and blow-up wig that Pandemonia has become world-famous for.

“I sort of joked in an article once that I’ve got an inflatable ego and then I go home and I’m just totally anonymous,” he laughs. “Everything deflates and that’s it – it’s gone. And it’s really nice just to sort of turn it off.”

But he knows that it’s a liberty that other celebrities aren’t able to enjoy. “I think it’s a real privilege, and I think privacy is something that is very, very rare, and it’s very hard to keep hold of,” he says. “But I’ve also found it very difficult to be anonymous – it stopped me being able to connect and hang out with people, like normal people do, or normal celebrities do. I’m always sort of behind the artwork, shielded behind it. But then I’ve got this other freedom – I can just walk off into the sunset and I’m free.”

And it’s this anonymity of living a hybrid life, one part being “real” and the other being behind a mask, that gives him insight into what some are looking for from an alternative identity in the metaverse. Maybe Pandemonia is in fact the original idea of being an avatar, crossing freely between two worlds – and in one of them your identity is determined by your own artwork, with you deciding how you look.

“Hello! I’ve been talking about this stuff for 15-plus years,” he laughs. “I mean, the idea in my mind was to create this persona but instead of having a virtual avatar on a computer screen it was to make it real, bring it out into the real world. I was thinking about how I can sort of interact with society and create this new art – and that was the objective with Panda.”

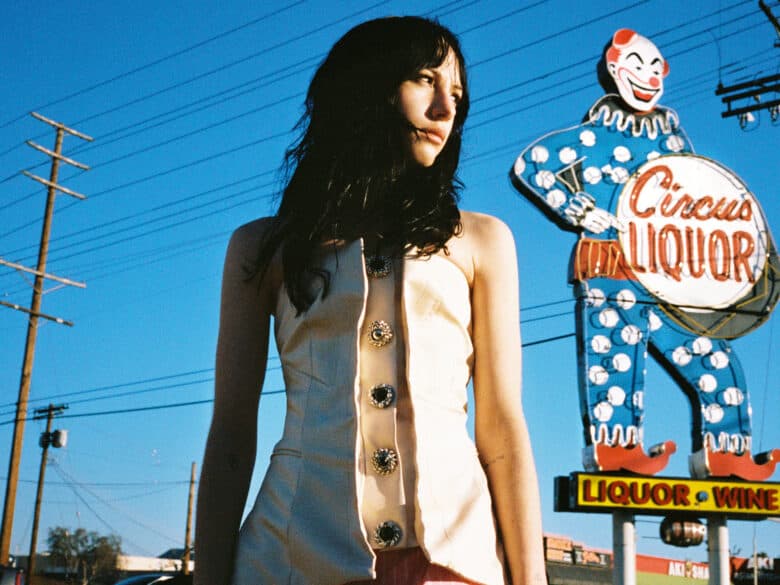

She came to life in 2009, a 7ft-tall, larger-than-life depiction of the tall, slim, glossy female celebrities of the time – complete with an inflatable white dog called Snowy. “I thought it would be great if you could have a piece of art that could fit in with these celebrities that were everywhere, as at the time art only really worked in a gallery, it didn’t really work outside that,” he says. “Yet celebrities could sort of move from film to television to radio to a newspaper article. They were sort of nebulous, they could shift through these different mediums, and social media too, which was just starting.”

Pandemonia was an instant hit with fashion week and events organisers and her outfits (that took hours of studio time to create) were the perfect fodder for Instagram. She was giving art access to new platforms that hadn’t been interested before. “I just went to places and people turned their phones and cameras onto my artwork and it went viral. It started appearing in the newspapers with all the other celebrities – it was a sort of commentary on the celebrities and the newspapers, carried by the same newspapers.”

The idea for Pandemonia stemmed from the artist’s interest in semiotics and the work of the Canadian philosopher Marshall McLuhan, whose “the medium is the message” thinking, which professes that the way content is delivered could affect our state of mind more than the content itself, couldn’t be more relevant in this age of social media. “I think it puts a big pressure on your mental health, and not just what you see on there but the chasing of hits and likes – that’s really stressful,” says the artist behind Panda. “The fact that you become dependent on the dopamine hit that numbers give you, you end up spending a lot of time on social media and suddenly you’re making stuff specifically to go on there. So, I’ve pulled back from social media a lot this year. It feels like you’re working for them, but I’m not working for them, I’m working for me. I’m an artist and I just make work because I like it, not because social media likes it.”

Pandemonia herself is evolving alongside the artist, who is currently working on a Pandemonia product collaboration with a global restaurant chain. “For Pandemonia, I started off doing the appearances but it’s moved to designing products,” he says. “I seem to be going back to doing more kinds of traditional art, I’m going more virtual. I don’t necessarily mean in digital and NFTs, but using Pandemonia in paintings and drawings rather than the physical appearance.”

So what does he think of digital art? “I think art and the metaverse are closely intertwined but in more than the way everyone thinks. In a way, the metaverse is another form of capitalism, another form of monetising our imagination,” he declares, talking about the metaverse having access to our innermost thoughts and desires because of the level of anonymity that comes with being behind a screen as an avatar. “It’s a way for our private lives to be monetised – like the way Instagram has been used to sell products, the metaverse is another way of capturing our imaginations. It’s also an attempt for corporations to move away from public accountability. Some of these [digital] worlds are created by corporations and they control the rules and laws – it’s not like the real world where we have some form of democracy, where we all vote, where we have a say in the laws of the land. But in the metaverse you don’t. It’s a dictatorship. It’s owned by someone else.”

He’s particularly pissed off with Meta. “You have to have a Facebook profile to even set up your [Oculus] Quest VR headset, which is ridiculous. I just want to use VR and have a go on this product to see what it’s like but you have to be on Facebook to use it,” he says. “So I have to create a new profile and it’s very intrusive. The other thing is these platforms force you to define your identity along their terms. We’re all made up of multiple personalities, we’re not all just one identity, and the problem with this social media thing is it forces you to define yourself in one way and I think that’s really problematic.”

This point hits a nerve with the artist, which is no huge surprise as Pandemonia was always about celebrating the fluidity of identity, but he does recognise that in general we are becoming a more inclusive society. “It’s definitely changed – in the past, coming out was such a big thing and people don’t really care about that any more. We’re really open to the trans community too now,” he says. “It’s really loosened up – we’re more comfortable with multiple identities.”

And Pandemonia has not aged at all: she remains as relevant today as she was when she took a risk and walked into that first fashion show. She’s an example of our abilities and desires to be more than one-dimensional, whether that’s in the real world or a digital space.