The Future: Olivia de Berardinis

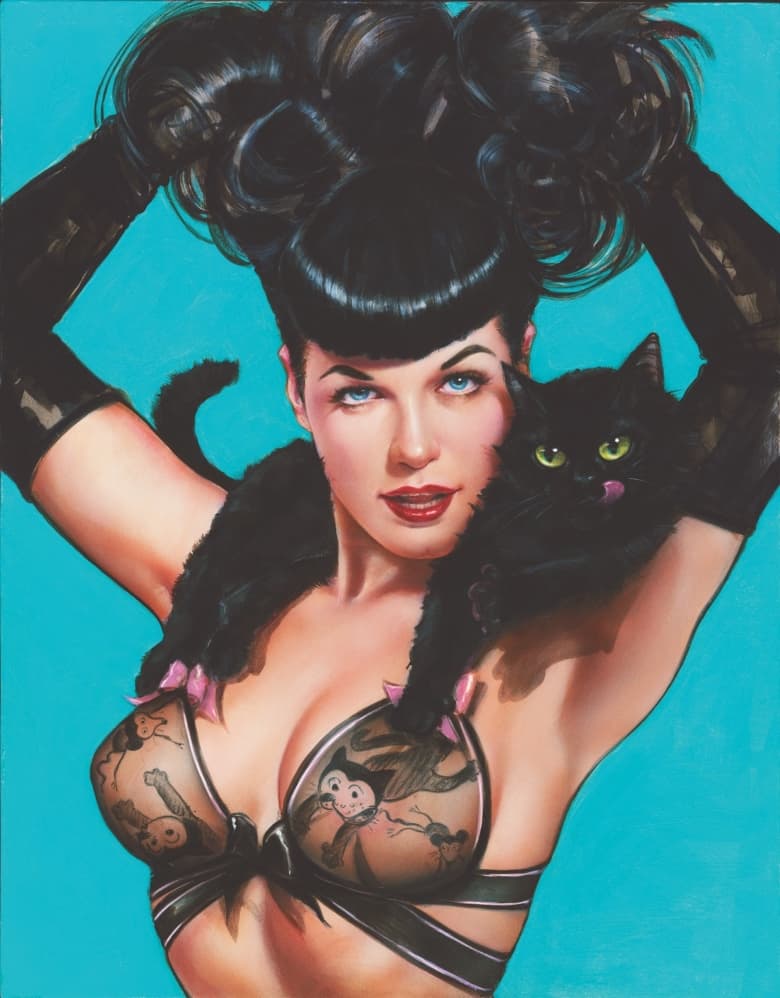

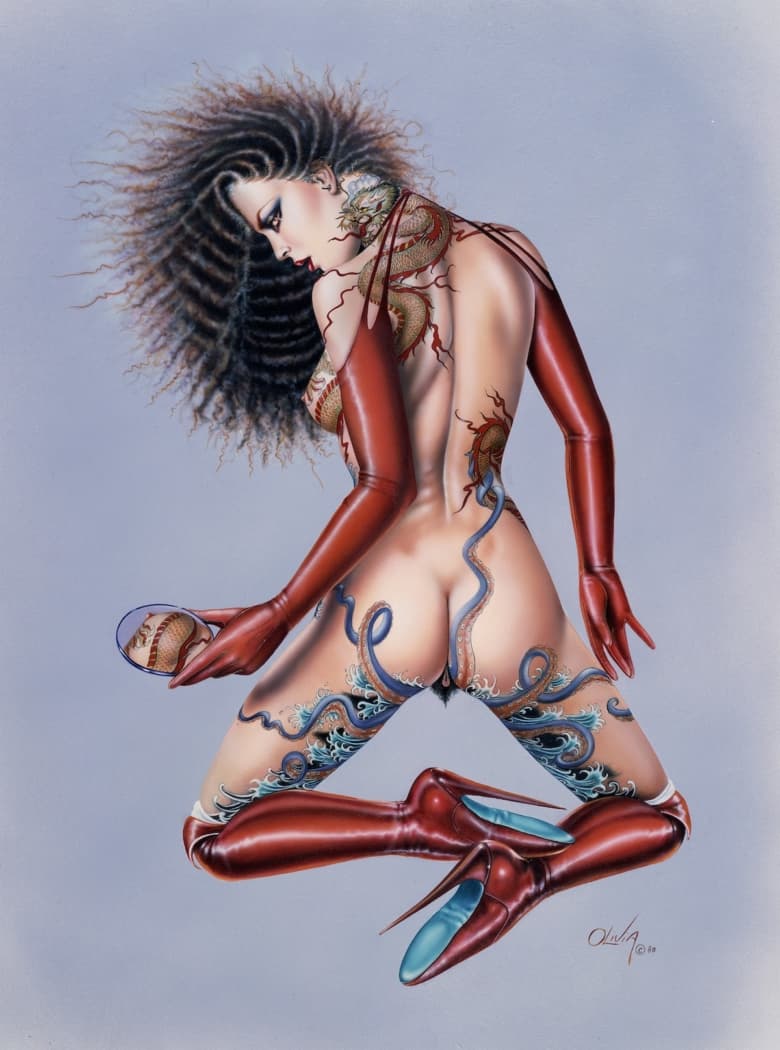

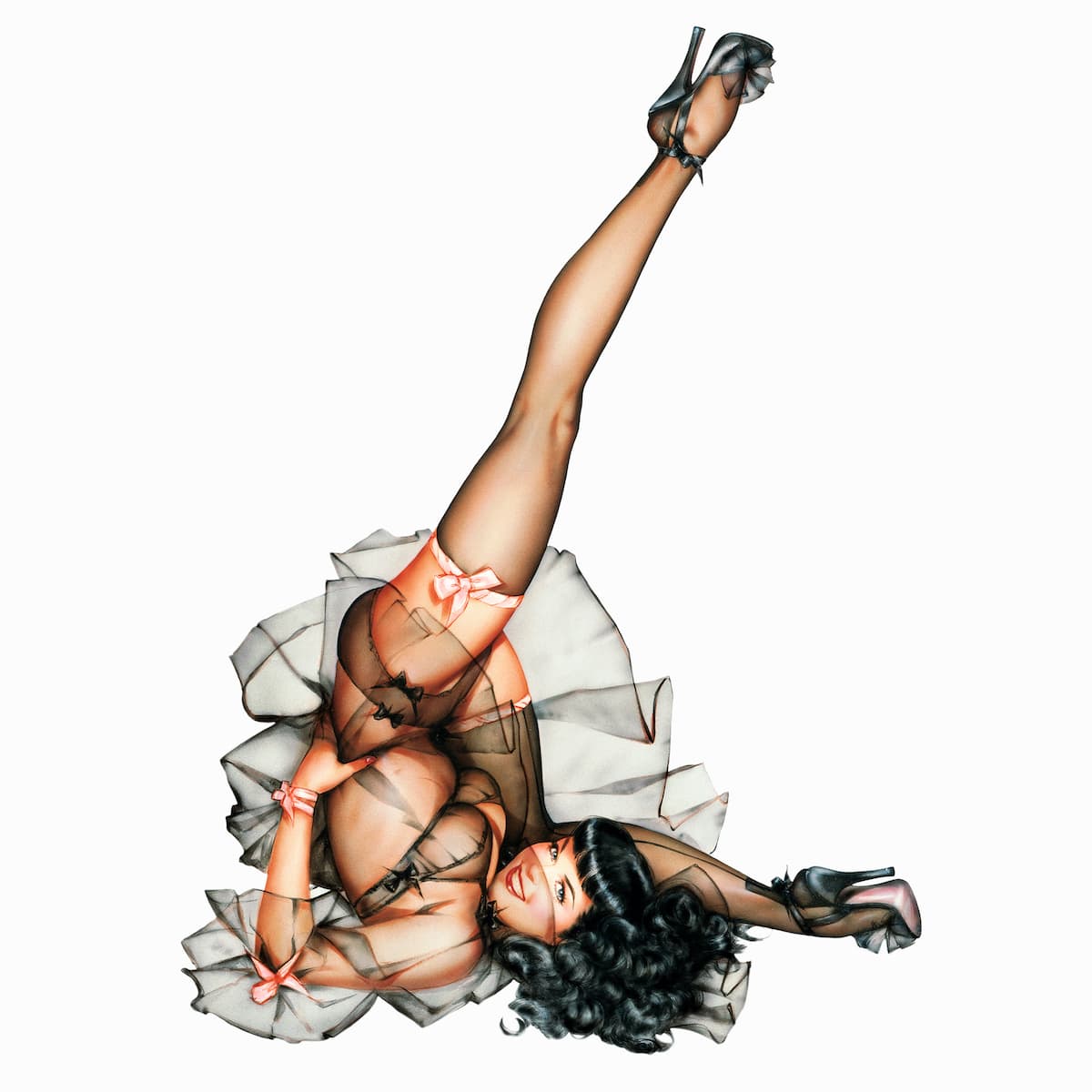

For as long as I can remember, the name “Olivia” could only mean the Olivia De Berardinis. Like (Joaquin Alberto) “Vargas”, in the world of erotic art – pinup, sci-fi and fantasy – the single name Olivia functions eponymously, speaking to her prolific 45-year career, in which she has moved fluidly from early minimalist paintings to Playboy centrefold illustrations and Heavy Metal cover art. Her oeuvre of baroque and surrealistic tableaux vivants is inhabited by (mostly) nude women lustily bursting out of images with coy and lascivious solicitation. These women were diverse before there was a political imperative on visual culture to heed to such ideas. With a fantastical command of high fashion sensibility and advanced anatomy, she created human – if not humanoid – characters bearing zoomorphic bodies, goth stylings and curiously peremptory gazes. I’ve always suspected that the peculiar power of these avatars-on-page has less to do with a mere mutation or technical evolution of the pin- up “tradition” than a rupture in perspective from the outside. The source of this rupture, the terrain and history of its outside, perhaps more aptly understood as the inside of De Berardinis’ artistic cosmos, has largely been a mystery to me. Here, for the first time, I spoke to her about these wild women and the life of the woman who has given them life …

My first exposure to your work was through my father. He had a subscription to Heavy Metal magazine and a copy of each of your books. I now have them myself and often turn to them while in my studio. As a kid and teenager, I was immediately taken by the world of erotic fantasy, but by your work in particular. How did your relationship with Heavy Metal begin and what was your interest, if any, in the world of fantasy and sci-fi erotic art when you began working with the magazine?

When I was frustrated by the gallery/art scene of the early 1970s. Few women artists were shown, and fewer made a living. Working nights in Greenwich Village, the waitress nightlife culture was killing my soul. I quit my waitressing job and began to support myself by illustrating for sex magazines. Sexual liberation was the zeitgeist of the time. There was something compelling about entering this netherworld. I was titillated by being in a man’s world. I just wasn’t supposed to be there, it was forbidden territory. I thought it might be a fun temporary job until my “real” career started.

When I started painting, I wanted to create a more “present” woman, who was in control and had an active part in the sexual act. I was always disappointed by the crudeness of how women were depicted in American erotica. There was no power, personality, or nuance – they were badly drawn and vulgar. I thought since I had some technical skills, I could depict women with dignity. The magazines I worked for didn’t have many rules, it was rather liberating. Many times they let me do what I wanted. So I started painting all kinds of fantasies, and to my surprise, they printed them! Sometimes I threw all kinds of objects and absurd scenes into the work, thinking there was some fetish for it, and lo and behold, most of the time there was!

Joel [Beren, her husband] went to the Heavy Metal offices in 1985 and showed them some of my work. That’s when we started a long relationship. Only a few years later we became friends with the new owner of Heavy Metal, Kevin Eastman, co-creator of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Most covers were mined from my early work and paintings from my many shows. We were commissioned for a few covers, and they were often of his wife Julie Strain – she was a favourite model and friend, and we had introduced them.

The intersections of erotic fantasy and sci-fi cultures are arguably catering to a primarily male audience and readership. Yet, what I find so interesting is that these worlds – the texts, images, comics, and so on, generated within them – are rich in ways that estrange them from erotic image production at large. I’ve thought about the “nerdy” consumer, how their status as somewhat outside a more predictable male sensibility could generate interesting mutations in the way bodies are represented and desired. The women in Heavy Metal, and especially in your work, are often powerful warriors, commanding beasts and machines alike. Does it differentiate the nature of your work that you’re a woman creating images of other women? How do you see questions of women’s equality at large, and the erotic representation of women in the fantasy context?

Not to diminish the breathtaking pin-ups that men do, it’s just logical that I have a different viewpoint – men rent, I own. I’m pretty typical of most artists – that is, different from the norm, shy, withdrawn. In the sexual revolution in the 1970s, there was a golden age of sex magazines and porn. Pre-AIDS, all things were possible, there was an openness to sexual experimentation. I did some of it in real life and experienced most of it on paper, feeling safer there because, in real life, sexual freedom did not work for everyone.

Most of the freedom belonged to men, the consequences fell mainly on the women. This left me a bit pissed. So in the adult magazines I was, most of the time, given free rein to do what I wanted, and what I wanted to do were sexually hungry, dominant, aggressive, beautiful women of all colours and in all forms. That would explain the warriors, wings and striped creatures you are talking about. I had a great time, I painted everything. If you saw those paintings today you would be shocked by how genitalia-explicit they had to be – it was the norm for that kind of publication. I did not want to shy away from it, I wanted to compete. To this day, I’m still expanding on the same theme, but in pop culture.

I remember reading in one of your books about working with Joel. How has your relationship evolved with your practice and career? In what ways has your love informed the work itself, if it has at all?

Joel and I grew up dreaming of an unconventional life. It’s a bit of a joke we have together, that we wanted the lifestyle of the original Addams Family TV show. I think we came close with our version. We married in ’79 and we share our days together, creating our pin-up world. Joel gets stuck with the business, managing, publishing, and so on, but he also does the nude photography I use as reference for my work, and so he “endures”.

Joel collects vintage erotica – French postcards, Weimar ephemera, fetish art by John Willie and Eric Stanton, pre-Second World War erotic stereoscopic photos, etchings by Norman Lindsay, von Bayros and golden-age pin-up magazines. Joel’s penchant for these collectables, his passion for going to flea markets and antique bookstores, has added texture and context to my art and life. His opinions have often influenced my art and we have many “discussions” on whether a painting is working or not. Ultimately, the many books we’ve made over the years are our attempts to put our creative life into print.

You say, quite endearingly, that you fell back on skills you “gained as a child” when referring to painting women. Can you give me a picture of what this part of your childhood was like? How were these skills developed?

I am an only child. My parents would always give me a stack of paper and pencils to entertain myself. My first drawings were of my mother, Connie, and she loved to pretend and dance around the house nude. She was a tomboy, and when she was small, had six brothers and three sisters, so nudity was not an issue. She was athletic, beautiful, and funny.

My mother was my biggest inspiration. Pre- war, she was a Rosie the Riveter, working in a Boeing factory, drilling bolts into airplane wings. She later joined the army, where she met my father, had me in ’48, and afterwards studied to be a clothing designer. She had many jobs. I watched her fight her battles in seamed stockings and high heels as she sold Avon cosmetics and plastic dinnerware door to door. During the early ’60s, she threw huge, heavy sacks of mail alongside men who did not want her there, and she drove the big mail trucks. The dreams of the women of her generation were marginalised and hard to achieve. Connie was one of a growing movement of post-Second World War women who joined the workforce. What unified the experiences of these women was that they had to prove to themselves, and the country, that they could do a “man’s job” and do it well. I witnessed the frustrations that arose from her ambition and desire for advancement, knowing she was more capable than most of the men around her. So when I first drew, my mother was my muse and then I became my own.

During my explicit erotica days, mid-1970s, I couldn’t afford models, so I put people together from the pictures I took from magazines and pieced them all together. I started using models in the ’80s because I knew it would make a big difference in my art. I knew I had to have some real women, not make them up. Without the reality to play off, made-up ones had no character. When we finally did it, I loved having a real person and playing off her sexuality, her joy. I enjoyed making them happy, it just felt right. Some of them would give me their all, give me great face and poses, and I would find it so generous for them to trust me, us.

As someone completely taken by the beauty and power of your work, the women who are part of it, I wonder, have you ever dealt with criticisms over the images you produce from a feminist perspective? If so, how did you deal with them? What power, sexual or otherwise, do you see in the women you depict and create?

I rarely get complaints. I have always been a feminist. I won’t presume to know what my work means to others, and I won’t apologise for what I like to paint, or how I’ve survived. I spent too many years worrying about how my work has been perceived. What I realise now is that some part of me liked the discordance, and my artwork does represent who I am and the times I came from. I’m a feminist and I don’t care any more if I don’t fit the guidelines. One of the biggest rewards of my career is how many female fans I have. When I started, they were all men, now half are women. They get me.

How has your aesthetic generally shifted over the course of your career – are there periods that you recognise looking back as having particular thematic or formal shifts?

In a 45-year career, there’s so much overlap, and somewhere in there is a large portion of Playboy in our life. Hugh Hefner mined a lot of the early work I did for erotic publications, Heavy Metal, gallery shows, and used them for the invitations for the legendary parties at the Playboy mansion. We went to 100 parties over the 30 years that we were regulars at the mansion. It was in 1999 that Hef decided to give me the classic Vargas page in Playboy. Pin-up by me, captions by Hef. Sometimes they came off a bit strange, but classically vaudeville funny. Artwork was done by a woman, caption by a man, so there were some surprises.

Hef created an empire based on the aesthetic of the pin-up, so I had the perfect forum to learn this seemingly simple but, in actuality, incredibly difficult discipline. I was honoured to have his trust and he was generous in giving the page to me. It was the best place in the world to learn pin-up.