The Future: Trevor Paglen

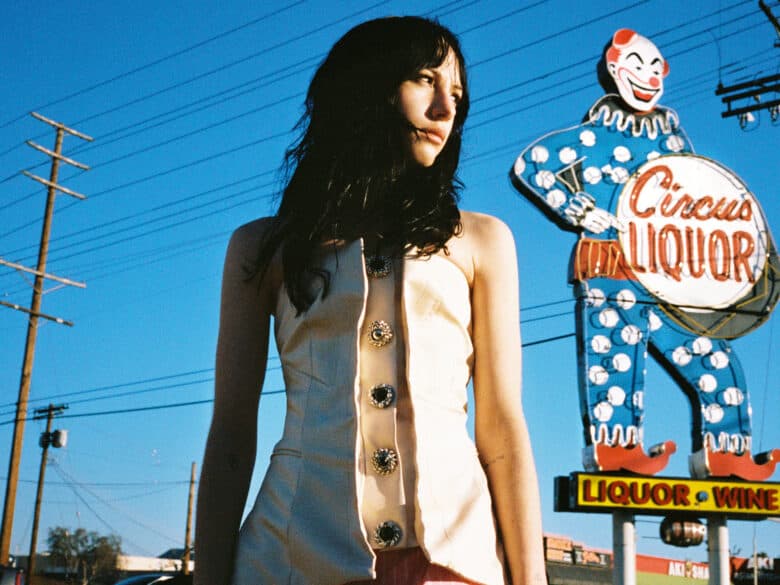

“My work is concerned with trying to see things that I think are really important to think about,” Trevor Paglen tells me over the phone while he’s on the way to the airport. “It’s not really about seeing the future per se, but seeing what seeds of futures are already here.”

Paglen, an intense American artist living in Berlin, works to focus the gaze of the public on where power lies. In doing so, he brings to light the trajectory that the future – unseen, unwritten, and unevenly distributed – might follow. He came to prominence in the early 2010s with a series of works that documented the hidden footprint of the military-industrial complex in the US and UK, through photographs of drones and black sites developed using the thinking of landscape painting. Reapers and Predators, unmanned killing machines made by private contractor General Atomics, in billows of Turner-esque cloud, and classified surveillance stations as night-vision Constables: what was hidden was made visible and hung on gallery walls.

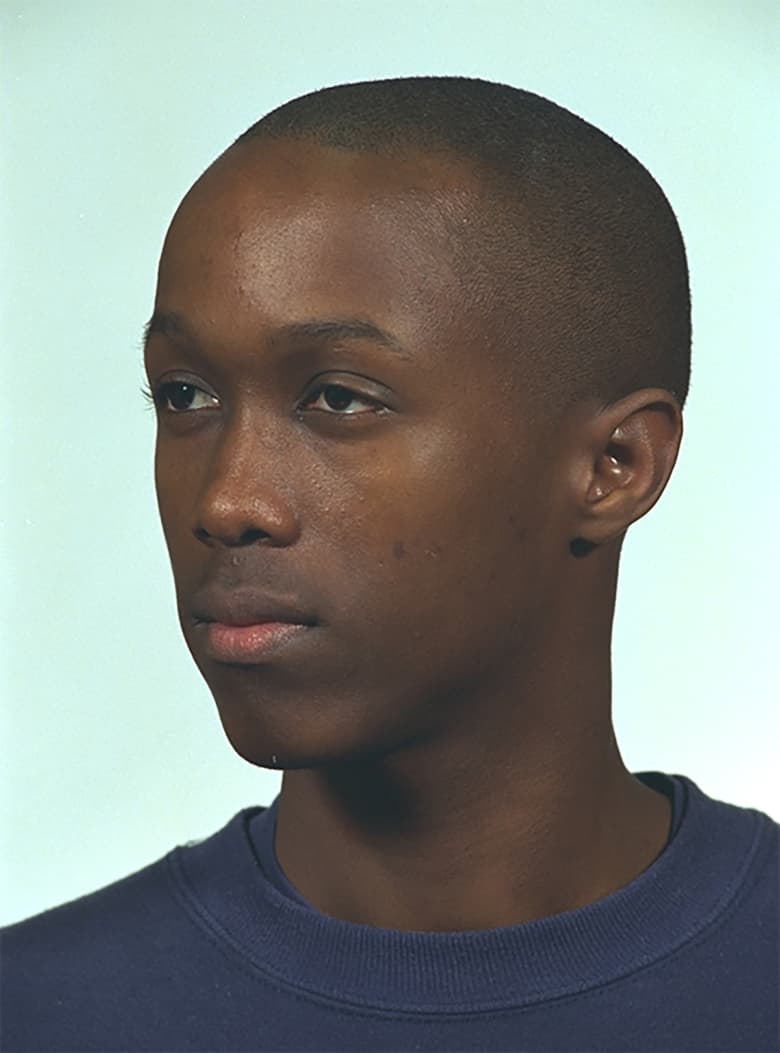

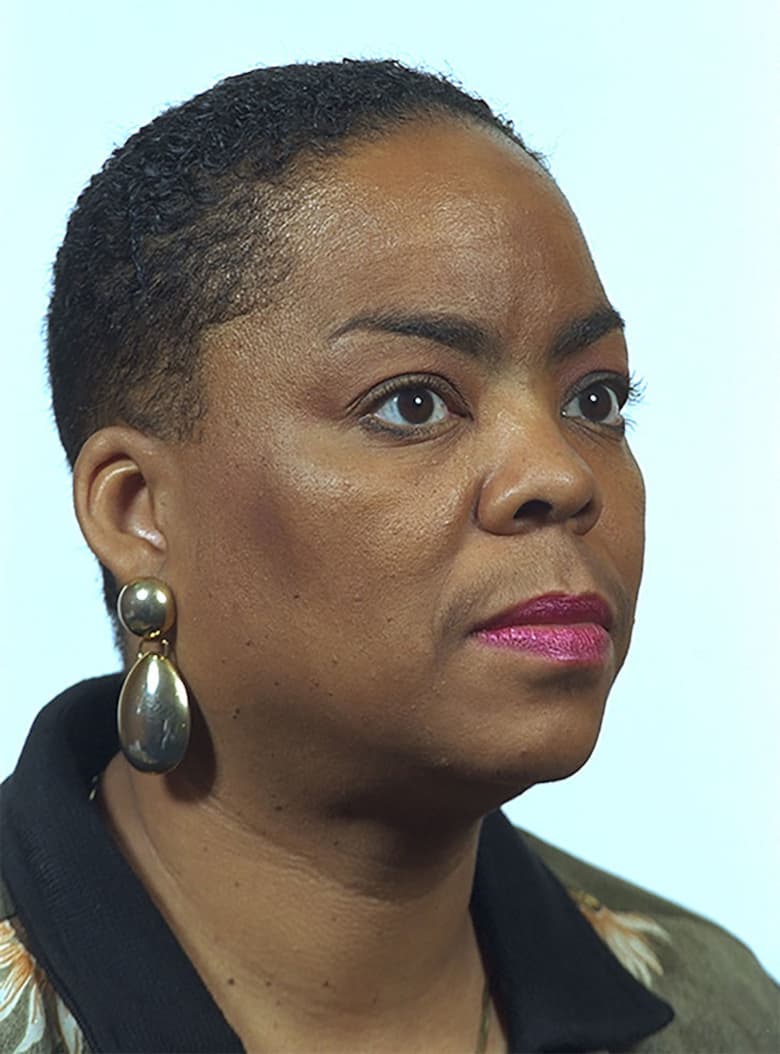

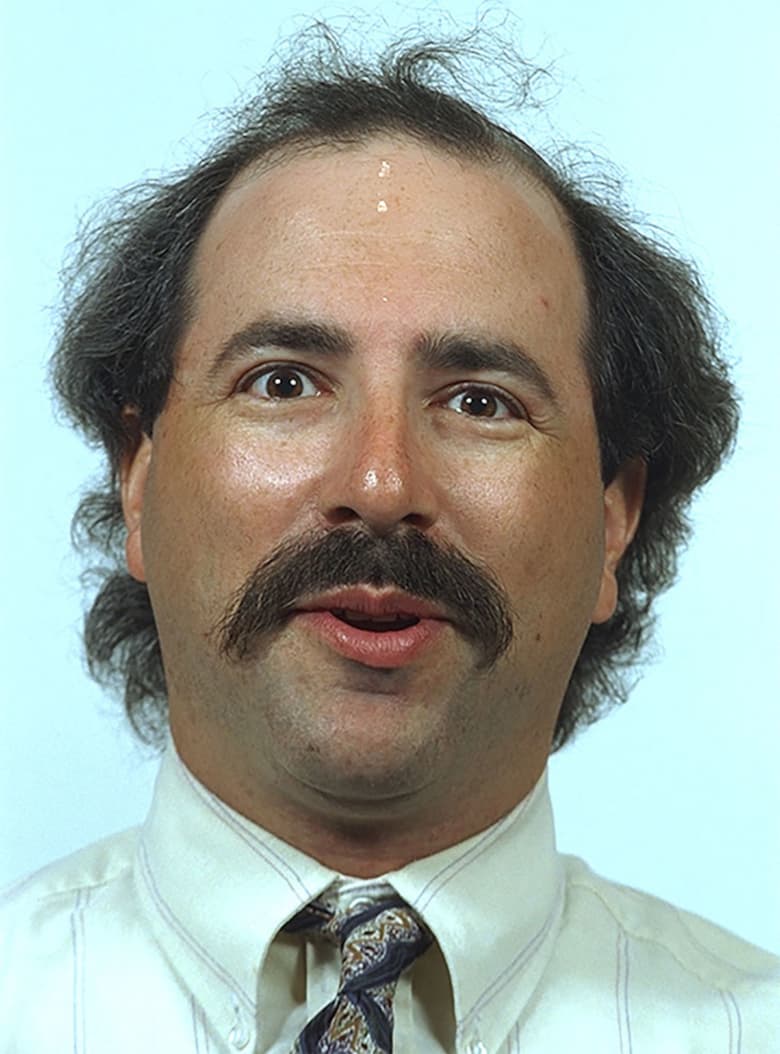

Today, the majority of images produced around the world are never viewed by human eyes. Instead, they are viewed solely within the black box of a data farm, by algorithms and engines that constitute what we call artificial intelligence (AI). Responding to this profound shift, Paglen has, in recent years, redirected his attention to projects that address the might of machine vision, moving from military power occluded by force to technological power occluded by volume. The most recent of these was Training Humans, a collaboration with researcher Kate Crawford shown at the Fondazione Prada in Milan that exhibited thousands of the portraits used to train AI machines to observe our emotions and categorise our statuses, whether professional, economic, or legal.

Alongside such work comes a suggestion of a brighter tomorrow in the form of Orbital Reflector, a program of sculptures as satellites built to orbit the Earth – one was launched into space on 3 December 2018 – that will appear in an exhibition scheduled to open later this year in Turin. It is, Paglen has said of this project, a way of imagining a sky that wasn’t out to get us.

Do you think the future actually does exist in any meaningful sense?

Yeah, absolutely. The way that I think about the future is not a wide-open field where anything can happen. A lot of what the future is has already been set in motion. In many ways, the future has already happened, it just hasn’t taken place yet. If you think about climate change, that has already happened. It’s taking place and unfolding more and more, but that is an inevitability at this point.

I’m curious about your relationship with the past in this context, particularly with the cultural past.

I try to assume that, with anything you’re going to look at in the world, other artists have been looking at it for thousands of years, whether that’s the sky, the ocean, or the stars. Your job is to figure out how to notice what is distinct about how these things look [today], in the way that they speak to your moment in time. Art has been looking at stars for tens of thousands of years – how is looking at them now, in 2020, different from looking at them in 2000 BC or 200 years ago? That’s not to say that history repeats itself. It’s that, in making art, you’re not only having a conversation with the other people who are alive today, you’re having a conversation with your ancestors as well.

The notion that the future is already prescribed, that the wheels have already been set in motion, is a really troubling and fascinating one. It harks back to the classics, right?

Maybe …

A literally fatalistic view that, say, Oedipus was always going to end up gouging his eyes out. The circumstances might be different and the conditions might be different, but the event was inevitable.

The thing I would take issue with within that description would be that idea of the future “naturally” going in one direction or another. I think humans are definitely responsible, it’s not up to anybody else. What’s helpful to me when thinking about the future that way is ideas around how you can take responsibility for decisions in the moment with the understanding that they might have consequences over time. For example, if you make nuclear waste, nuclear waste isn’t just a problem today, it’s a problem for thousands of years into the future. How do you think about the ethics of what one is doing individually, or technological systems or environmental systems? How do you take responsibility for them, not only for the present, but for the futures that they create, that are inherent within them?

You’re touching on the existential anxiety and terror that a lot of us feel around these locked-in changes. How do you deal with these futures as a person? Also, how does your work as an artist deal with this?

As a person, I don’t know. I think about this every day. I think it is genuinely horrifying and perplexing and, to a certain degree, unknowable. I was in Australia in December, basically in the midst of the whole country being on fire, and that felt like a vision of a future that is here already. Seeing how people are responding to that, and the government basically denying that it was linked to climate change. Seeing people, on the one hand, struggling to normalise that, which is one very understandable response, but on the other hand, seeing people trying to get away from it. Seeing all these dynamics in place.

In terms of your question, of how does one resolve it in one’s own personal life, I think it’s just something that one knows about and sits with. The specifics of how it is going to play out are not necessarily predictable and you don’t know how you are going to respond or the responses of what people around you are going to be. With my work, there are a number of projects I think about materials for and think about what sorts of politics, what sorts of futures in a way, are concealed in different kinds of materials.

Could you go further into why you think politics is an idea of the future?

I guess when you’re thinking about something like artificial intelligence, one can imagine that it is something mathematical or technical, which it is. But there’s much more to it. For example, if you want to get AI to work, you need to have huge amounts of data. Where do you get that data from initially? From harvesting people’s data or scraping the internet and putting that data in centralised locations. So we can see in that step already that there is a political form, which is a mass data extraction and consolidation process. If you’re going to have a company organised around that, then there is a political form that the mathematical logic implies. If you want to build a neural network based on that model, the consumption in terms of power is enormous, from things like oil or coal. Now you can start thinking of AI in terms of “AI is burning coal” or “burning oil” – it has an environmental footprint. Who is able to benefit from these kinds of systems? It’s big corporations, it’s the police. What kind of systems of power are being consolidated through technological architecture and at whose expense? How do those political and environmental formulations go forward into the future or sculpt the future? That’s my own thinking, thinking across sectors and seeing them as interconnected in ways that we might not conceive as related to each other.

I’m really interested in how you come up with images that in some ways suggest a way of seeing what is occluded. I think what is interesting about the work you are producing at the moment is that the sphere of occlusion has moved on from an official secret to something where the sphere of occlusion is computer vision. As in, we literally don’t see ImageNet, but it’s not something that’s hidden, it just does not exist in terms that human eyes can see. Your thinking now seems to be about spheres of occlusion that are down to size. So if we split that question into two, firstly, could you speak about the move into occlusion just by sheer volume? And then, what are your thoughts on how the rise of the machine eye will shape the world to come?

It depends on what kind of perspective you want to take it from. In terms of a history of vision, it’s an enormous development in the idea that, historically, images have required a human to look at them in order to exist. An image that nobody ever saw basically didn’t exist, but that has changed now. The ability to build machines to look at and interpret images independent of a human has multiple implications. One of the political implications of this is that the interpretation of images is always a form of politics. What you say an image means is a form of power. Who is determining what the meaning of images are in AI systems or in computer vision systems, and what is being done with that information, are forms of power. When you look at whether it’s a corporation that’s trying to harvest data about you, or an intelligence agency or a police department, it’s formed by the political work that someone seeing that is trying to do.

If the police want to use facial recognition to identify every person in every photograph, there’s a certain form of seeing that you’re doing there, you’re not trying to see people’s backgrounds and environments, or you’re not trying to see images in a literary kind of way. You’re trying to see these images in a forensic way, and there’s a kind of power built into that way of looking. If you’re Facebook and you’re trying to build an AI that identifies things in pictures that people upload to their profile, you’re trying to learn something about people. You’re going to do facial recognition on it and you’re going to identify what kind of clothes they’re wearing and you’re going to use that as a proxy for how much money they have, and you’re going to see if they’re drinking Coke or Pepsi. All these forms of information you’re going to collect by looking at their photograph. That’s a very different way of looking than sharing a family album with your friends, say.

When you think of something like computer vision you’re tempted to think about it as a technical system, which it is as well, but I’m interested in the ways that politics are built into it. A lot of the work I’ve been doing is looking at trying to see what kinds of politics are built into autonomous forms of seeing. That’s where you get into this ImageNet stuff, because you’re like, “What kinds of misogyny are built into this?”, or “What forms of structural inequality or cruelty are built into this?”, “What notions of normalcy are built into this?”

For example, what does the term “accomplice” look like compared to, say, the term “doctor”?

Exactly. Especially when you look at images of humans, there are thousands of categories of people that have been created and labelled into categories. Even to say if someone is a man or a woman without asking them, that is a judgment and a form of power. It’s time we recognised that.

Where should we be looking?

On everything. The way that we learn how to see, you can literally look at everything. But what kinds of relationships and forms of politics are congealed in the things around us? You can do that as much for a street as you can do for a phone or the atmosphere itself.