This is Activism: Venetia La Manna on exposing fast fashion’s unscrupulous practices

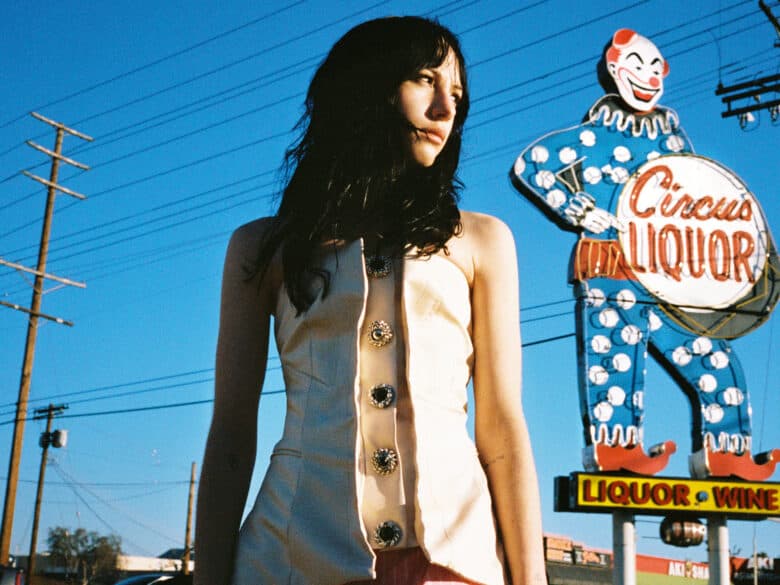

For anyone well travelled in the social media universe, Venetia La Manna is probably a name, face or voice you already know. Her videos call out some of the fashion industry’s big names for over-production and their approach to workers’ rights, filmed while she whips up, say, her plastic pancakes (ft adidas) or greenwashing pasta (ft Boohoo). Across all the major platforms, La Manna is calling for collective action, with the aim of building a more sustainable future.

The London-based 32-year-old is rewriting the rules of being an influencer. Her commitment to fast-fashion activism began while she was working in television as a producer. There, she honed her skill in utilising social media to be a platform for good and as a means to educate her viewers. Targeting brands like PrettyLittleThing in support of hardworking garment workers and debunking myths like “vegan fashion is not exploitative” in a video directed at H&M has resulted in more than 200,000 followers on Instagram alone.

“Fashion activism for me looks like disturbing the status quo and ultimately trying to uproot the current fashion system. This is a system built on a colonial past that prevails today. Garment makers around the world, including here in the UK, in Leicester, are being exploited for profit.”

In 2020, Greenpeace reported that, in the UK, we buy more clothes per person than any other country in Europe, with 300,000 tonnes of garments burnt or sent to landfill each year. Last year, Statista reported that worldwide consumption will increase from 168.4 billion pieces in 2021 to approximately 197.3 billion by 2026, meaning that those tonnes of clothes heading to landfill will increase dramatically.

La Manna discusses how her work aims to tackle the biggest businesses in the industry because research has been published asserting that 71 percent of the world’s greenhouse-gas emissions come from just 100 companies. But with this, La Manna acknowledges the privilege that comes with being able to live sustainably and preaching this lifestyle.

“I’m never going to call on someone who is less privileged than me. However, there are many influencers at my junction of privilege who know better and are still feigning ignorance. They are a huge part of the problem because they are perpetuating overconsumption of clothing that was created under exploitative conditions at a huge cost to both people and planet.” La Manna uses the money she makes from her podcasts and protest work with other activists to support efforts aiming to solve issues like “the textile-waste crisis, or that only 2 percent of garment makers worldwide are earning a fair living wage”.

Last year, La Manna participated in a protest against Missguided: “We – Labour Behind the Label, Oh So Ethical, Stitched Up – organised actions against Missguided, whose suppliers were owed millions after the brand went into administration [last May], which meant workers went unpaid and lost their livelihoods. We got to meet some of the workers and hear about their experiences of working with Missguided and their demands.

“I would love to get to a place where any member of the public can walk into any shop and know that an item of clothing has been made by someone who has had a safe place to work, was allowed to unionise, receive paid time off, paid overtime and had all of their needs met. Ideally, these garment makers will have equity in the brands they work for, too, and the billionaire CEOs will re-distribute their wealth.”

La Manna’s research reveals the uncertainties surrounding brands’ declarations about the sustainability and ethical practices they follow and highlights the prevalence of greenwashing (a company’s activities that make people believe it is doing more to protect the environment through, for example, its pro- duction processes than it really is). She stresses how adopting a new approach to clothes can bring joy, and not in the way we are predisposed to think it does. “I really do feel like, especially as women, so much of our consumption when it comes to fashion comes from the mental health crisis we’re in. We buy fast fashion and constantly buy new clothes as a way to make ourselves feel better. But we’re actually being robbed of this potential joy that we can find when we buy less and learn to create solid relationships with our clothes. With our own individual shift in living, we can band together towards collective action. This means that our changes in lifestyle will positively affect [individuals] like garment workers.”

La Manna points out how people in countries that are the most impacted by climate breakdown are often responsible for the fewest carbon emissions. “But we have to think of ourselves as one network, one community,” she continues. “I think that leads back to this, like that feeling of joy – this interconnectedness that we have with everyone on the planet.”

Taken from HUNGER Issue 27: Call to Action. Available to buy here.