Tom of Finland & Dreamy: The exhibitions dissecting queer fantasy, identity and tender reality

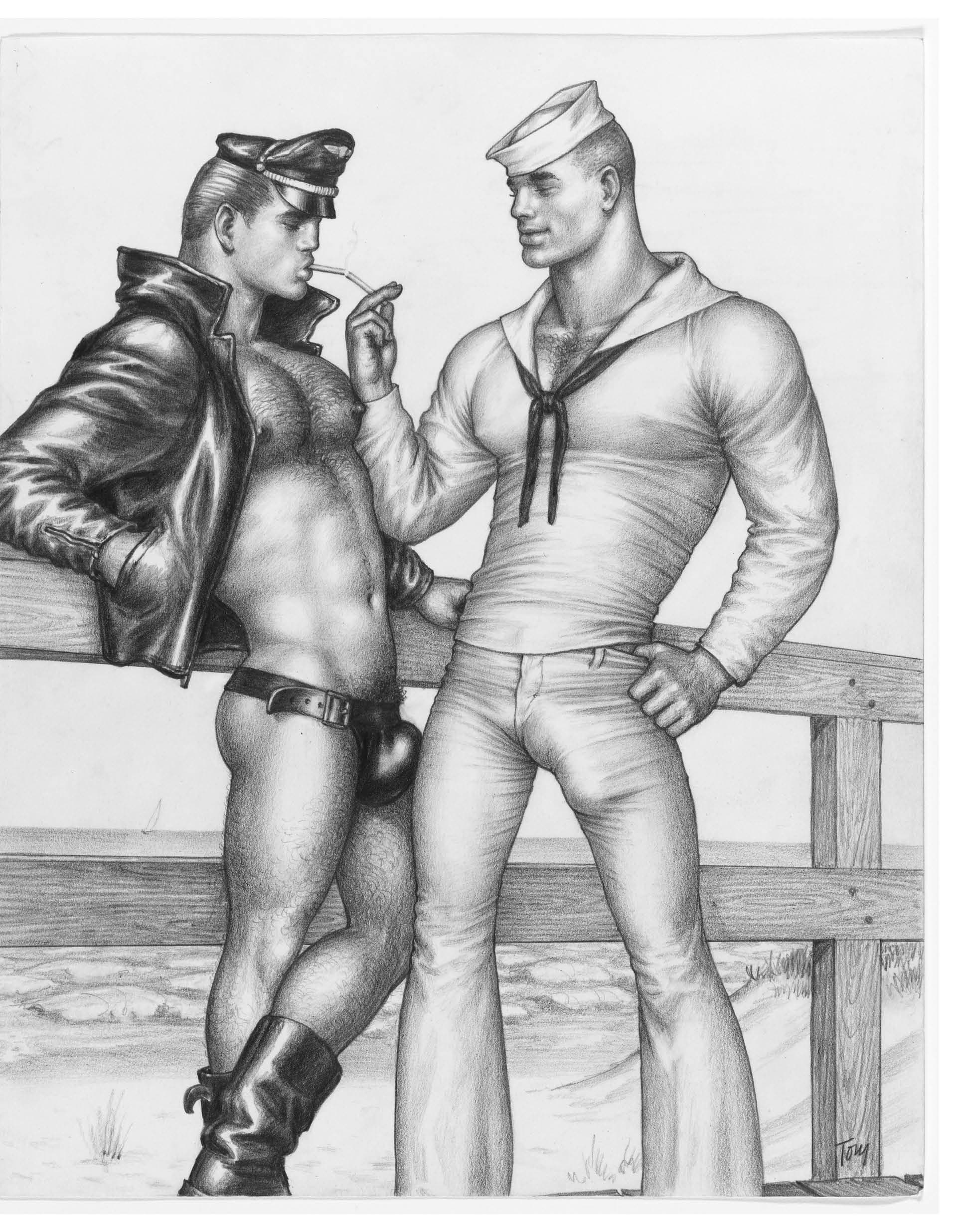

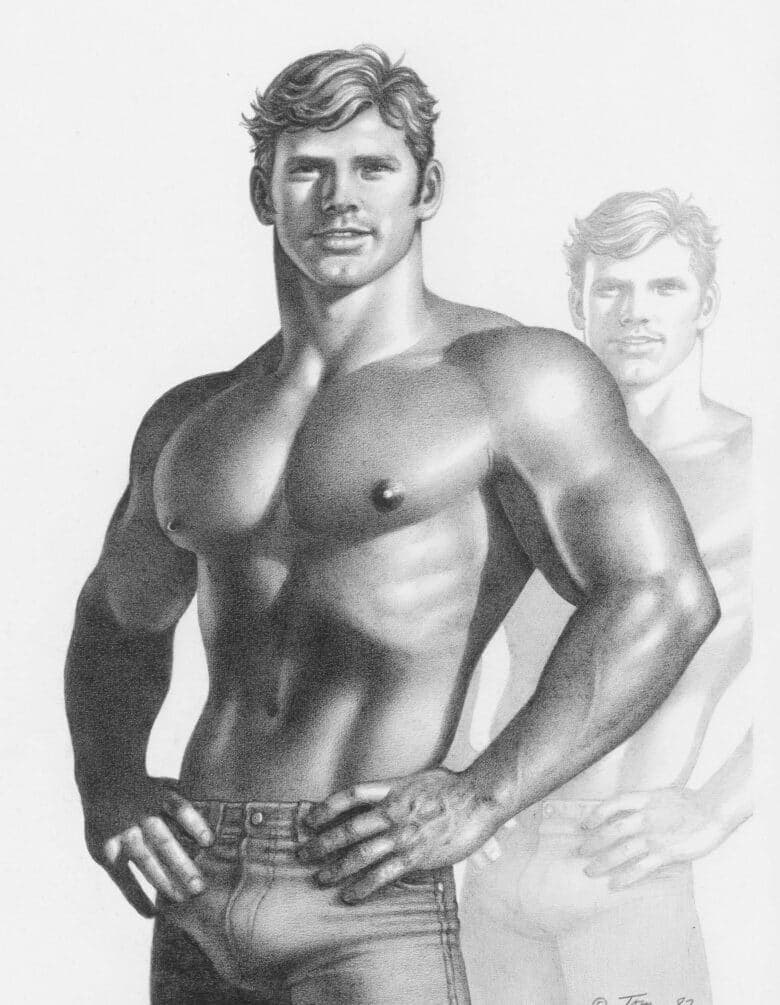

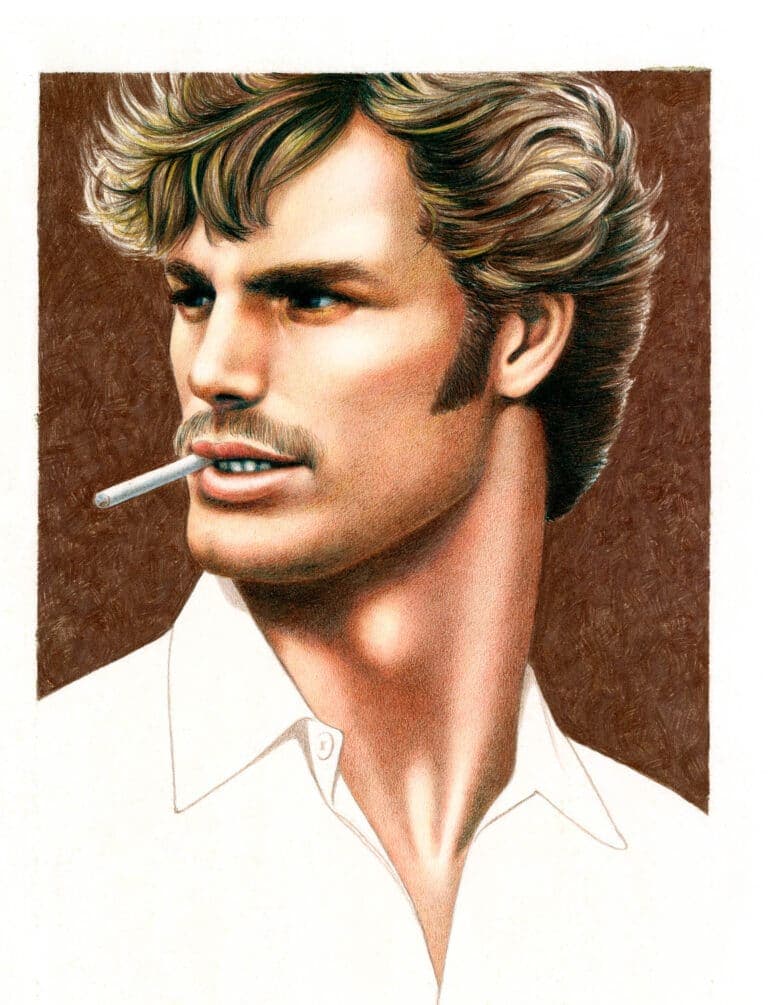

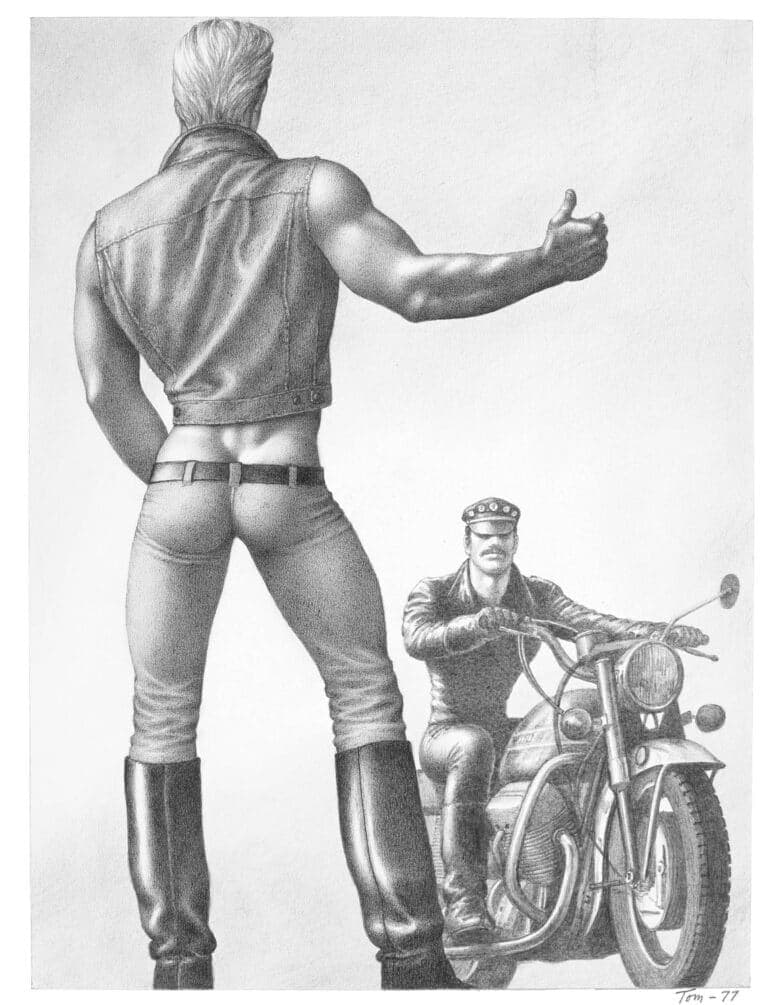

When standing in a room surrounded by Tom of Finland’s drawings it’s difficult not to feel just ever so slightly insecure. It is, to put it lightly, everything that a lot of us are not. Big, bulky, objectively gorgeous men with bums capable of generating their own orbit, and bulges under jeans or leather accentuated and exaggerated to the point of equine anatomy. Ethereal faces shaded with wispy pencil lines that make the men tantalisingly masculine with their strong moustaches and bold eyebrows, yet cherubic in the desire we may have for their perfect complexions and god-like facial structures. There’s a confidence within them, one that’s either relatable, admirable, or unbelievable. And as you stand in the middle amongst the drawings that only hint at homoeroticism, the ones that could only be more erotic if they were a live-action performance, as well as the photos and references that inspired it all, the balance of desire, truth and fantasy is what brings the artist’s work to life.

The retrospective of Tom of Finland (né Touko Valio Laaksonen), entitled Bold Journey, at Helsinki’s Museum of Contemporary Art, Kiasma, curated by Museum Director Leevi Haapala and Chief Curator João Laia, spans six decades of the artist’s working life. From the very first drawings of clothed men with their lingering gaze, to the portrait of Tom by Robert Mapplethorpe, to the full blown sex scenes, it is quite understandably a vast display of leather, muscles and well-endowed men. Pulling artworks from the Tom of Finland Foundation in LA as well as from the collection of the Finnish National Gallery and private pieces, at the heart of it all is an array of queer fantasy. See, it’s not so much about the super-idealised male form amongst queer folk (especially now at a time when the consensus is that beauty and attraction stretches beyond muscular physiques and big penises); that may have been how it started, but what rings out is how all of these characters – the men within the drawings – only scratch the surface of our reality.

Born in Kaarina, Finland, in 1920, Tom of Finland’s drawings acted as a daydream that subverted the status quo of homosexuality. His characters included lumberjacks, policemen, bikers and soldiers, men of a traditionally hyper-masculine and heterosexual environments where homosexuality, back in the middle of the 20th century, would have only found its place in the inconspicuous corners of their existence. Like the male sexworkers (Tetki) of Russia at the turn of the 20th century or the parks and public toilets in various countries that were used as cruising spots for gay men, Tom of Finland’s works used space as a means to depict his characters’ intentions, whether overt or not.

Bold Journey gives way to a thematic curation that plays with the ideas of conceal and reveal within gay culture, especially in the mid 20th century. That has meant that the exhibition can be divided into the characteristics of either the men in the drawings or the spaces in which they can be found. For example, Outdoor: Fun in the wild or Sea & Harbor: On the waterfront, these are the spaces that posed discrete opportunities for like-minded men who were searching for discrete interactions. Or Geared up: Uniforms and leather which presents an aesthetic that identifies a shared fetish. All of this constructs a narrative that takes secrecy and entwines it with opportunity.

At a time when being gay was a crime and fetishism was seen as an illness, the drawings became a chance to take reality and turn it into a gay dream for himself and eventually for others. Kiasma’s exhibition is a celebration of the mass of work – a lifetime of drawing fantasies – which also landmarks progression. All you have to do is stop someone on the street in Helsinki and ask who the country’s most famous artist is to find out the real reach of Tom of Finland. Go into a bar (gay or not) and you’ll see curtains and decorative pieces with the artist’s signature drawings plastered all over them. Step into the opening night of one of the artist’s exhibitions and you’ll be pushing through a crowd of men dressed head to toe in the leather outfits pulled straight out of the drawings. It’s not so much a cult following, it’s a global fanbase that champions the liberative and lasting effect of Tom of Finland. In short, there’s more to it than genitalia and it’s not necessarily, as some may posit, pornographic, it’s more longingly biographic. And that’s what threads an undercurrent of despondency throughout the exhibition; the very fact that what Tom of Finland created was born out of fantasy, like a lot of queer work is.

That slight sadness, perhaps predominantly felt by queer viewers (I’m afraid I can’t speak on behalf of the heterosexual audiences that go and see it), is carried past the final display in the Tom of Finland show. You travel through the exhibition, slipping on the VR headset to tour Tom of Finland’s LA home, trying not to fall off of the stool when standing at the top of the VR staircase, and the exhibition doesn’t end, but another begins.

Curator Max Hannus’ Dreamy – Queer Imaginaries sits as both a compliment and a continuation of its preceding show. Dreamy showcases a range of multidisciplinary artworks from various queer artists that highlight the experiences of the creators. Whilst on the very face of it, the exhibition is an add-on to Tom of Finland in the fact that it is queer and about queer experiences, but what runs much deeper is the fact that Dreamy actually contrasts Tom of Finland and builds upon what we have already seen.

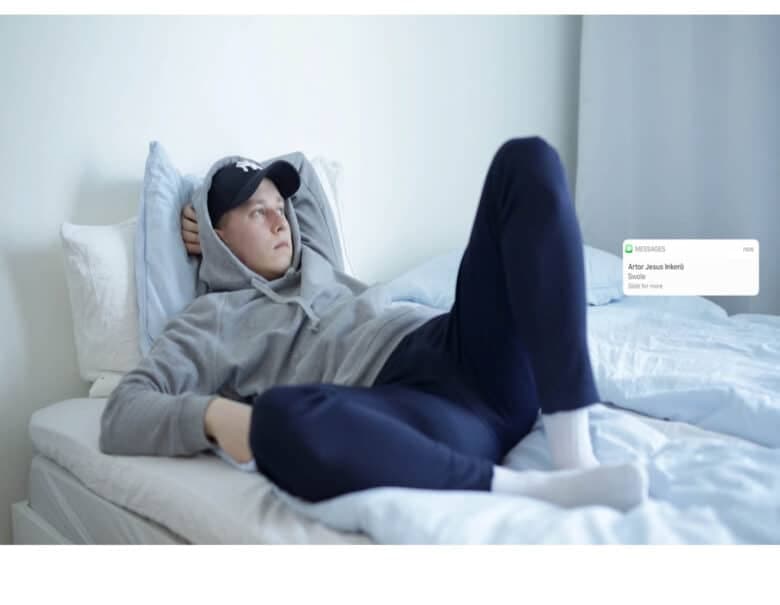

In the opening room, Artor Jesus Inkerö’s video Swole questions the idealised male form, flipping between a young person laying on their bed texting their friend – “I wish I was a bullet pig already. The thicker the better” – to being thrown into a world of bodybuilders determined to reach their perfect figure, whether that’s attainable or not, and whether perfection is achievable to any degree. Opposite, Anne Koskinen’s Torso VI is a torso carved out of natural stone, deliberately androgynous showing only underwear and the lower half of a stomach. The underwear is visible, though it could be anyone’s. It is smooth and carved with precision in the areas that it matters, again pulling at the tension between perfection and the body. The opening pieces of the exhibition feel automatically more relatable and more in touch with where the current mentality around “perfection” sits nowadays. That’s not to say that Tom of Finland’s work is out of date by any measure, but it is a reflection of the times.

“I think it’s important to have different bodies and different queer experiences to be represented, since being queer is all about diversity,” Hannus tells me, who also anecdotally says that their mum has Tom of Finland bed sheets. “That desire is something that is a very basic human thing and having a body is a human thing, seeking pleasure is a human thing. But then there are different kinds of marginalities and different kinds of margins where people operate. This is both a celebration and also focusing on pain and the difficulties in seeking that connection.”

In its similarities, the Tom of Finland exhibition has an obvious element of the hidden experience; being with someone of the same sex out of sight, behind a tree or in a sauna, which elevates a deep rooted feeling of guilt and shame, even if not visible in the characters’ expressions. And whilst Dreamy offers more around the subject of self-acceptance, often accepting one’s own queer self means wading through the guilt and shame that eclipses it, brought around by a world that has been dominated by heteronormativity and incessant oppression.

Kalervo Palsa, a Finnish artist who died in 1987, has his works in the next room, ones that quickly catch your eye and distract from the two Nan Goldin photographs opposite. They pull elements of Hieronymus Bosch tied up in fantastic realism scapes that merge a dream-like world with very raw depictions of men, women and animals. ‘Knights of the Chocolate Hole’, a fleshy, garish and visually abrasive painting shows one man having sex with another who has his own penis thrust in his mouth. Appearing static but with a profound force, one man holds his hand behind his head choking a woman who lays naked behind him. Their limbs confuse themselves with one another, all figures seem entirely connected but incredibly reluctant. The genitals themselves are not in any way desirable like those shown in Tom of Finland’s drawings, they’re like pulsating, beastly, curved oblong tumours that dictate our focus.

Just beside ‘Knights of the Chocolate Hole’, another watercolour painting, ‘Friends of the Gale’, presents an image of a half-man, half-cat figure having sex with a man who lays dead in front of it, whilst slitting the man’s back with a blade like punitive lashings. Behind them, a flying hare with a large (Tom of Finland ‘large’) member approaches the cat-man from behind. Again, the painting is unsettling, calming in its colours and stacicity, but leaves you with a feeling of torment around penetrative sex, particularly sex between two men – a far throw from the rather arousing drawings just a few rooms back.

“[The guilt] is an interesting reading of it, first of all because for me it’s something that I totally recognise in my life and in experience overall,” says Hannus. “However, I would rather try not to go there. So somehow processing that is very important. It’s like a form of therapy even, to show that and to process that and to see why is there guilt related to sexuality: Why is sex and sexuality that kind of a thing? It’s totally a form of oppression that is placed upon certain sexualities and certain experiences that you’re supposed to feel like it’s not alright. You’re supposed to fix it or hide it. And that is just tragic.”

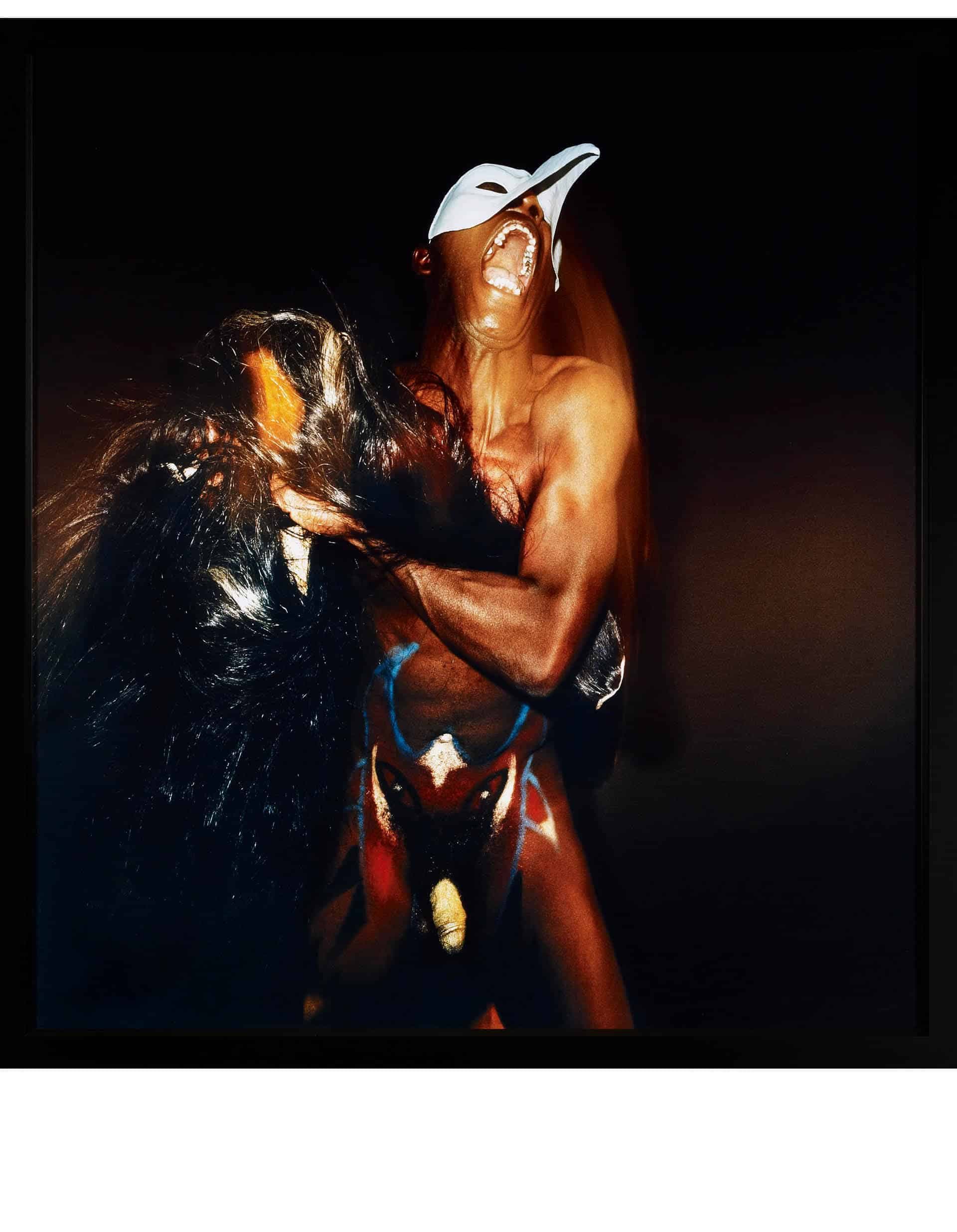

But Dreamy does also have those important moments of joy that are also as prominent in many queer experiences, such as Goldin’s ‘Pawel Laughing on the Beach’, Rotimi Fani-Kayode’s ‘The Golden Phallus’ and ‘Nothing to Lose VII’. That rests as the crux of the tangent exhibition, the focus is not solely on the downcast queer experience, but on queer identity as a whole – an exploration of identity that stretches beyond the walls of Kiasma and out across the art world of Helsinki in general.

Just around the corner from Kiasma is another of the three museums that make up the Finnish National Gallery, Ateneum, which houses the country’s biggest collection of classical art. A Question of Time is the museum’s new collection exhibition after its reopening this year, and it tackles contemporary notions of identity head on whilst reflecting on the country’s art historical narratives. It ruminates upon the question of who art is for, and rather, who is it to decide that? Divided up into four themes, The Age of Nature, Images of a People, Art and Power, and Modern Life, it poses one pertinent question: Who are we in and amongst all of this? “This” being a country’s history and heritage, evolving societal developments, the effects of climate change, and what weight art holds in helping us understand all of it. Elsewhere in the city, at Taidehalli, a non-profit exhibition space, identity is at the centre once more within their Young Artists 2023 show, including works that delve into the cruising spaces of saunas and traditional Finnish woven rugs depicting experiences of trauma and loss. Discussions around who we are and where we sit are well and truly on the lips of the city’s busiest and well-loved art spaces.

Finland may be known for being home to some of the happiest people on earth, having some of the safest, purest drinking water, and being one of the only countries in the EU where homelessness is actually decreasing, but what also makes the country seem a million miles ahead is its approach to celebrating the art that has built its culture, and championing the artists who are propelling it further still. Tom of Finland sits comfortably as one of the, if not the, nation’s artistic hero, but a retrospective on him was seen as an opportunity to bring other diverse and multifaceted artists to the fore. Many of the works in Tom of Finland and Dreamy have an element of fantasy, desire, and unachievable dreams, but the charm is in stepping outside of the door, into the centre of Helsinki with the trams rolling by and the people with extraordinarily calm demeanours walking past and seeing the poster for the exhibition on the side of the building: a colossal drawing of a man with undeniably firm buttocks and a cocked knee hailing a ride from a biker who looks as if he’s been unknowingly waiting for a man like that to come along. That’s the effect of a place proud of its heritage and excited for its future. And if you don’t believe me, you can go and buy the bedsheets.

Find out more about both Tom of Finland: Bold Journey and Dreamy: Queer Imaginaries via the Kiasma website.