Why the metaverse is adding nothing to the music lover’s experience?

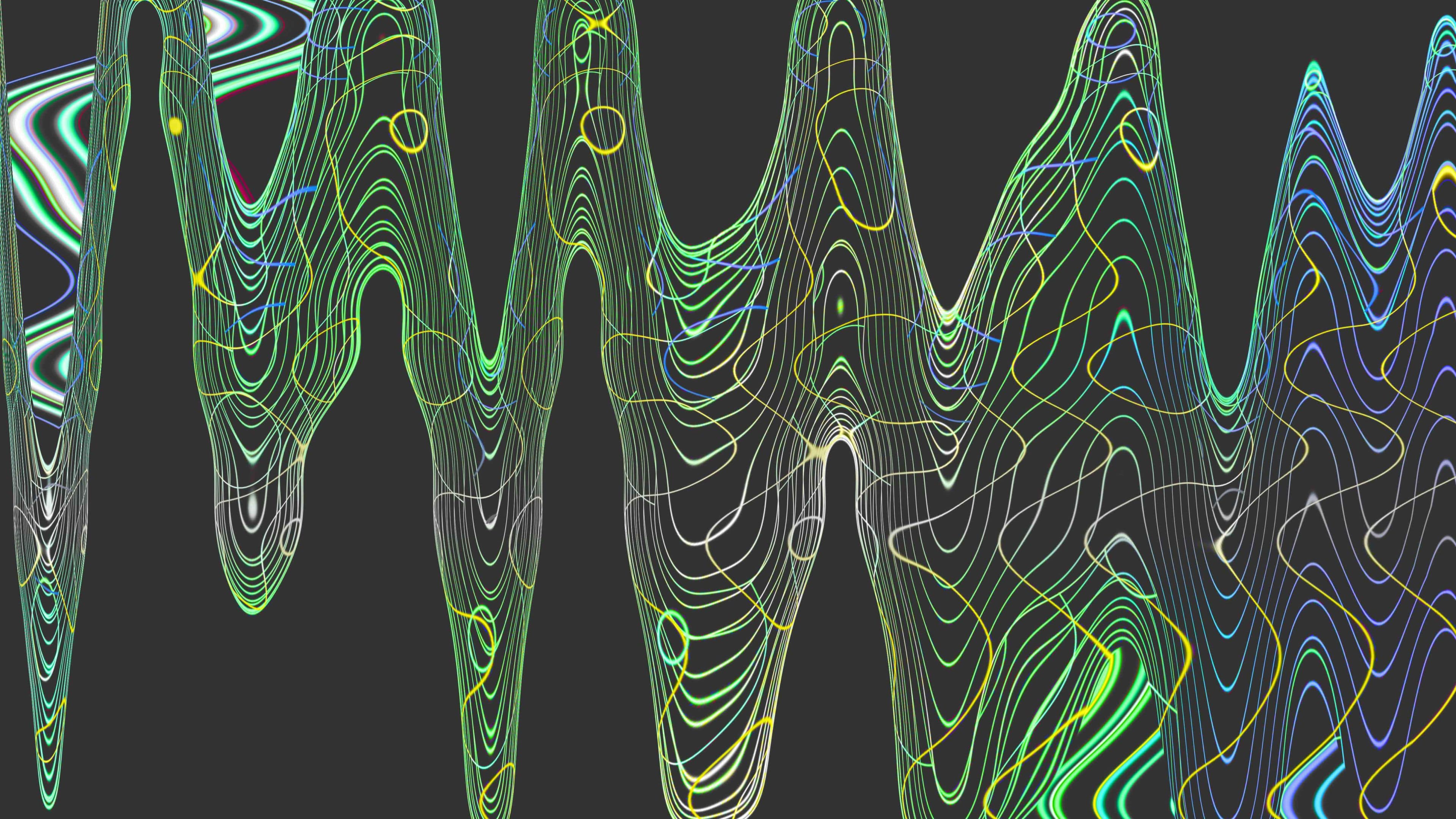

The West Side Story composer Leonard Bernstein had chromesthesia, a form of synaesthesia where sound is associated in the brain with a particular hue. He spoke about the “timbre to colour” – the colours associated with various sounds – that spontaneously arose when listening to music. That type of synaesthesia is not uncommon among musicians and composers, but technology could potentially allow the rest of us to experience it too – and without artificially altering our brain chemistry.

Tech is allowing for any number of ways for the public to experience music in new forms. Apps such as Thumper, Dance Dance Revolution and Beat Saber have gamified music, making each beat or bar the action that triggers a physical reaction from the player. Meanwhile, advances in communication platforms are allowing for remote collaboration between multiple composers at the same time, while other apps have democratised composition to even those of us without much musical talent. Technology is transforming music – so why is the metaverse, arguably the most visible example of transformative technology of the past year, lagging behind?

The examples of concerts and gigs on metaverse platforms to date have, for the most part, been recreations of their real-world counterparts. The skeuomorphism extends to the performers and artists appearing on a relatively mundane stage in a virtual environment, with only a handful experimenting at all, and even then, only in terms of the graphics that accompany the gig. The most famous and arguably most experimental, Travis Scott’s Astronomical event in Fortnite, only played with the scale and the form of the artist’s avatars. It was essentially a light show: very pretty, but just an extension of what is possible in the real world.

John Vlassopoulos is global head of music at metaverse platform Roblox, which last October hosted its “first metaverse music festival”, in collaboration with Las Vegas’s Electric Daisy Carnival (EDC). He told me that the goal was to recreate the experience of the real-world event by also recreating many of its trappings within the platform: “We thought if there was a sort of real-life manifestation of Roblox in terms of the magic and excitement that you can create in this online wonderland resort… in the real world [EDC] was close to it.”

Other high-profile gigs within the metaverse have taken a similar tack, to the point of recreating stadium concerts as closely as possible to the real thing. Platforms like MelodyVR allow users to effectively view live performances videos in 3D, and a Foo Fighters gig, distributed on Meta’s Facebook Venues platform, is a recording of the band that users can choose to watch from various balconies around the virtual environments. It is technically impressive – but also an extremely sterile and passive way to consume music in the metaverse.

That lack of inspiration speaks to the current lack of certainty when it comes to the metaverse: nobody knows what the space will ultimately look like and we are all trying to extrapolate from existing “micro-metaverse” platforms like The Sandbox, Roblox and Meta’s Horizon apps. It is a situation that is exacerbated by the drive from some companies to be the metaverse platform, interoperability and creativity be damned.

To date the vast majority of commercial metaverse spaces have taken inspiration from real-world environments. Meta’s Horizon Workrooms, for example, uses the awesome power of the Oculus platform to drop users into empty, lifeless office spaces. Other, better examples create spaces inspired by, if not directly modelled on, real environments, such as the recreation of the Royal Albert Hall for the most recent Fashion Awards.

By contrast, the metaverse and VR platforms that are pushing the boundaries of what is possible in the metaverse are those that take more direct inspiration from gaming. The gaming space has had more practice creating and playing with “unreal” spaces and consequently is often more inventive – creating environments that invoke that feeling of synaesthesia.

Some, like Beat Saber and Synth Riders, have succeeded in creating a new way to interact with artists’ catalogues. The likes of Lady Gaga, Imagine Dragons and Linkin Park have all licensed their songs to Beat Saber, for instance, allowing users to interact with them – and other players in multiplayer communion – in VR. But still, it isn’t a true metaverse experience yet, but I suppose it proves that the gamification of music deserves its place in the conversation.

In terms of accessibility, then, gigs in the metaverse and VR spaces already outshine their real-world counterparts. In terms of creativity, however, they are stifled by the desire to make what could be extraordinary familiar to the audience. Undoubtedly, the more musicians and artists look to the experiments in gaming and VR art spaces, the greater the potential for music in the metaverse to offer something wholly original. But despite the opportunity for the metaverse to reinvent the concert-going experience, it is extremely likely that it will just be an additive to users’ existing habits around gigs. As yet the technical limitations of VR and metaverse platforms only allow users to interact with spaces with a few senses at most. Sight, sound, proprioception can all be played with in VR, for instance – but touch feedback is still years away from widespread commercial availability.

As impressive as some of the metaverse concert experiences have been technically, and for all that they add touch points between artist and audience, they currently cannot recreate the heat of a crowded gig or the feeling of pushing past audience members to get to the bar. Platforms like Meta now include safety settings that prevent users’ avatars from coming too close to one another, which is fantastic for user safety but anathema to a real-world concert experience.

Technology has come a long way, and can recreate some of the chromesthesia that some people experience while listening to music. But when we talk about music in the metaverse, we are talking about an entirely different form of content, one that can be radically different – but not a replacement for real-world gigs. Music in the metaverse could be an entirely new medium – if we stop trying to force it to conform to the trappings of real-world experiences, which is where we’re at right now.