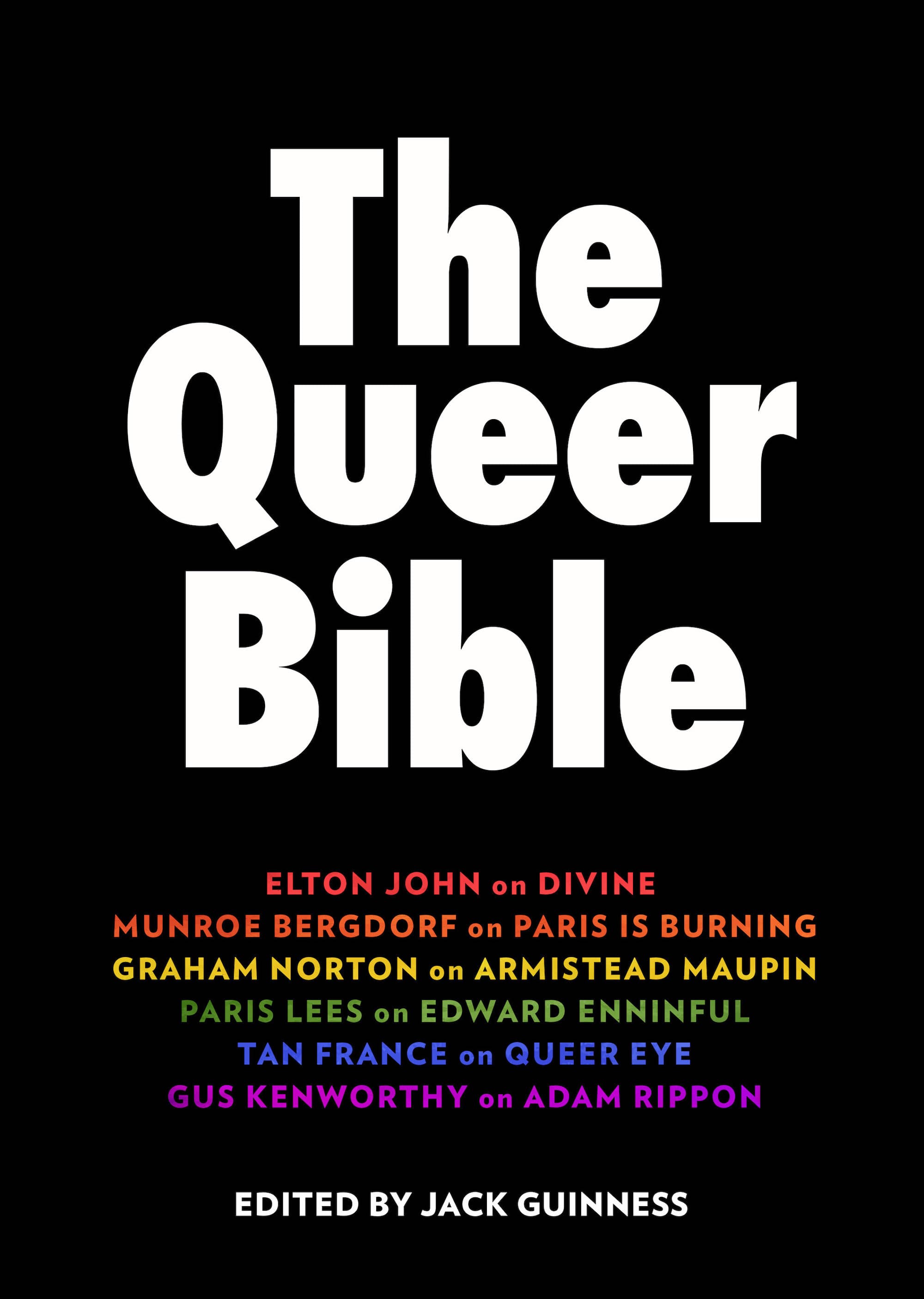

The Queer Bible

As the founder of The Queer Bible, an online magazine dedicate to all things LGTBQIA+ culture, Jack Guinness has been curating and uplifting queer stories for years. Now, the project goes from digital to print as The Queer Bible is released in book form, via a collection of essays by the likes of Elton John, Munroe Bergdorf, Mae Martin and more. Clearly, the need for diverse LGBTQIA+ stories is more urgent than ever as we grapple with the issues facing our communities – and this collection promises to introduce readers to the varying and multi-faceted perspectives of queer individuals at the top of their industries.

To celebrate the book’s release Guinness speaks to poet and personal friend Charly Cox about queer joy, LGBTQIA+ forebears and what he wants readers to take away from the collection.

I spent this morning finishing the book and I just sobbed my eyes out.

I know this is very perverse but it makes me happy that it made you cry.

I don’t think it’s perverse, you spent so long putting together. If it was just joyful, it would be an inadequate representation of the stories you are telling.

That’s the thing, the queer experience – or any experience – is about the agony and the ecstasy, the joy and the pain and that to me is at the core of the queer experience. There’s so much suffering to get to a point where you accept who you are and love who you are and then there’s huge joy. To me, that joy comes from when everyone is together, so bringing all these different voices with different life experiences together in this complex queer tapestry makes [The Queer Bible] really fun. It’s like being on a dancefloor at a gay nightclub.

That’s exactly what it felt like to read, except every five minutes someone would turn the music down and be like, “Guys, we can carry on dancing in ten minutes but we’ve just got to have a quick DMC in the smoking area.”

Or maybe a Robyn song comes on and you just start crying!

Exactly! So my favourite line from the book is in the introduction, where you write, “To know where you’re going, you have to know where you’ve come from.” That’s something I’ve struggled with for a huge part of my life, not in terms of my sexuality but in terms of my mental illness: not knowing where I’ve come from or what other’s endpoints look like. Where have you come from?

What really got me about this book is that it focusses in on the queer experience but by focussing in, it’s become a microcosm for everyone. All of us are reflected back in the essays and the biggest part of knowing where you come from is making sense of who you are. It takes a lot of sense to pause and make the timeline of who you are and I think it’s a really healing process. Then you take it out with yourself and think, “What have I inherited? Where am I from in terms of ancestors?” Not just biological ancestors, but cultural ones.

Looking back and thinking, “Wow, I’m descended from some pretty fucking amazing people.” That’s a really empowering thing to do. All the things that LGBTQIA+ kids get bullied for all the things that make them brilliant, special people later on: all that creativity and hypersensitivity that society wants to crush. My big thing with The Queer Bible and my life going forward is protecting those magical people, whether they are kids or adults, especially the trans and Black members of our communities and the lesbians who are often on the frontline fighting for oppressed, marginalised people.

Ten years ago, if you were to say to yourself, “Who am I and what’s going on next?”, do you think you would have been able to say what you just said with the same certainty?

Getting to a point where you realise that maybe the most interesting thing about you isn’t your success and isn’t even your suffering, but is other people outside of yourself: that’s the thing that has probably taken me a long time. The book has been a really humbling and inspiring experience, because The Queer Bible is not about me. It’s not about what I think, it’s not about me being a gatekeeper. We’ve had enough of white, gay men being gatekeepers [in the LGBTQIA+ community] and just white men in general.

I’m not going to disagree!

The book is about platforming other people’s stories and letting them tell them in their own voices and then I just stand back and watch all the beautiful stuff and connections happen. I’m really humbly happy to be part of it.

Through The Queer Bible, you’ve managed to build what you’d never think in a million years was an accessible tribe of people. The names in the book are outrageous, they’re horrifyingly amazing names. Was that terrifying, reaching out to contributors?

Absolutely. Everyone in the book is a friend of mine now but I get anxious emailing them, these people are my heroes. And I’m not anxious because of anything they’ve done, quite the contrary. They’re the sweetest, most calming, pleasant and humble people I’ve worked with. I’ve noticed that the more famous and successful someone is, the kinder and sweeter they are. I had a phone call with Elton John and he couldn’t have put me at ease more, he couldn’t have been more generous and he couldn’t have been more kind. I’ve described him as my fairy godmother. His involvement with the book has taken it to another level.

You’re holding a lot of weight for a lot of people, taking in these contributions, being the first person to read through them. That’s a huge responsibility and a huge emotional weight for you to open up a part of yourself to take it all in.

I feel a huge amount of responsibility to my contributors and to my artists, there are nearly 30 different illustrations in the book. I feel really protective of these people’s stories because they’re hyper-personal. They’re really about the moments in their lives that they struggled, realised who they were, accepted themselves, flourished, lost hope – it’s all there. These essays run the gamut of emotions. Graham Norton’s essay made me laugh in the beginning and then by the end I was crying my eyes out. Munroe Bergdorf’s essay feels magical, like a call to arms. I really hope that in the interviews I do and the way I talk about the book, that I do [my contributors] justice. If me doing an interview or a social media post helps get their stories out there even more, that makes me really happy.

I think a lot of people will feel this when they read the book but with every essay I really felt as though I was also holding a mirror up to myself. The way that I was responding and reacting to what I was reading was a direct reflection of my own little insecurities. Mae Martin’s essay forced me to look into my internalised homophobia around my own sexuality and how frightened I have been for so much of my adult life to delve into what I felt was an awful, angry Pandora’s box of bisexuality. I could never have said that to anyone, let alone on a Zoom call, until I’d finished reading your book.

Thank you for sharing that, that was really brave and beautiful. I’m happy that the work that someone else has done now frees up something in you, so that you can continue on in your journey. I really think a lot about the internalised homophobia, racism and misogyny that’s really prevalent, especially in the white gay male community. It’s so damaging for LGBTQIA+ people to grow up in a straight world, it’s damaging for everyone to go up in a straight world. I look at my straight, cis male friends and see the damage that toxic masculinity has done to them; how they’re not allowed to talk about their feelings, how they have to perform a very narrow sort of masculinity.

Suicide is the biggest killer of men under 35 and the majority of those will be straight men. No-one’s winning with the current system that we have. We are all damaged by growing up in this patriarchal society. So I really hope that in all that complexity and oppression, the main abiding feeling that we have is one of celebration, pride, self-acceptance and community. This book is like a little preview of when we can all be back together, dancing on a dance floor in a queer safe space, having fun with other people that are like us.

I can’t wait. My final question for you is: who is your dream person for you to put this gorgeous book into their hands? Who would it be and what would your parting words be?

A few years ago I would have picked a famous person. Now, I would give this book to any young person that feels alone and isolated or like a freak. I would tell them that this is your new chosen family and this is your inheritance.

The Queer Bible is out now.